Share this article

NPS adds two young males to mountain lion study

The Santa Monica Mountains of Los Angeles, where mountain lions (Puma concolor) prowl, comprise one of the only large metropolitan areas in the world inhabited by wild big cats. The National Park Service (NPS) recently fastened GPS collars on two previously unknown individuals in its study of this urban felid population to follow their dispersal, breeding and survival across the fragmented landscape.

“We were trying to catch a young female because her VHF implant had stopped working,” said Seth Riley, lead investigator on the 15-year-old study that now tracks 18 animals. “We ended up catching two young males.”

Once they noticed that their camera trap had captured images of an uncollared mountain lion by a carcass put out to bait the female, Riley’s team got a hold of one of the two males and tagged it P-55. But they left the bait out just in case.

After they released him, the researchers heard a scuffle. In the morning, they learned that another uncollared male had visited the bait. So they reopened the traps until they caught the culprit — as it turned out, the male from the photos. He became P-56.

“At the moment, there are more males in the Santa Monicas than we have ever followed before,” Riley, a wildlife ecologist with NPS at Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, said.

Between the ages of 12 and 18 months, young males leave their mothers to find a home range and breed, he said. But most don’t survive to do so because they’re impeded by huge highways separating the Santa Monicas from potential habitat in the north, cut off by other development, poisoned by rodenticides or killed by adult males.

P-56 has already reached the western edge of the Santa Monicas and come up against farms on the Oxnard Plain, Riley said, so the young male will have to go elsewhere.

“Young males we track are interesting in terms of finding out what the fate of the population is and whether young animals are able to disperse,” Riley said. “Hopefully we can continue to follow them and see where they end up.”

Because they’re large carnivores, mountain lions require an enormous expanse of space and are particularly sensitive to habitat loss and fragmentation due to urbanization, he said, and the Santa Monicas can’t support more than about 15.

“They’re the ultimate challenge for conservation in a landscape like this,” Riley said. “The Santa Monica Mountains are not big enough in the long run for a viable population of mountain lions. Connectivity across freeways is critical.”

NPS is enhancing existing highway crossings and working to establish a large vegetated overpass to boost connectivity, which will help increase genetic diversity, reduce inbreeding and moderate conflict within the population, he said. The agency is also tracking mountain lions in neighboring regions to better understand their movement across roads.

“We’re trying to increase their ability to go back and forth across the freeways,” Riley said, “for animals in the Santa Monicas to get out and for those north of the freeway to get in.”

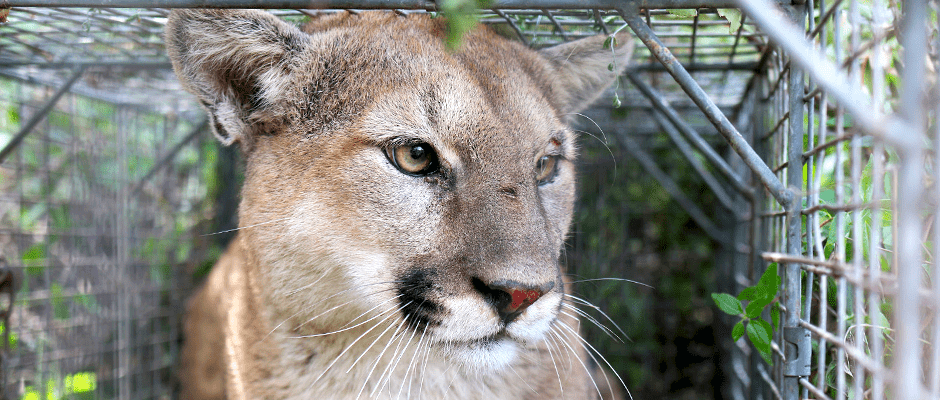

Header Image: P-56, one of the newly-collared young males in the Santa Monica mountain lion study, awaits release. ©National Park Service