Share this article

Large mammals could be irreplaceable, fossil record shows

The giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) has a sense of smell 40 times more acute than ours and flicks its sticky tongue over 150 times per minute to eat bugs without getting stung. Its unique role in the Central and South American rainforests and grasslands where it lives may make it irreplaceable in terms of its ecological function, according to a new study, and it’s just one example of a species whose extinction would create a gap in the ecosystem.

Matt Davis, a paleontologist with the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University, Denmark, set out to study functional diversity, the component of ecology that looks at the role each species plays in the environment. For the past three years, he conducted the first detailed examination of functional diversity in large mammals that roamed North America from the mass extinction at the end of the last ice age 11,700 years ago to today. Combing the fossil record, he identified these species and their traits to determine how comparable they were to one another.

“If you’re doing a job that no one else is doing, you’re functionally distinct,” Davis said.

Species that are similar, such as the bobcat (Lynx rufus) and Canadian lynx (Lynx canadensis), aren’t very functionally distinct, so they’re not as valuable to the ecosystem, Davis said. But some play such a precious role in their communities that other species can’t quickly take over for them if they vanish.

“If we lose just the giant anteater, that will cause about as big of a proportional drop in functional diversity as losing all the wooly mammoths, ground sloths and other species that went extinct before it,” said Davis, who published the paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Davis had set out to see if distinct species were more likely to die off than other species. That’s what scientists had expected, he said, but he saw no evidence of this in his results.

“You can be really distinct and go extinct first or be just like everything else and go extinct first, too,” he said.

But through his research, Davis found that because so many large mammals have gone extinct since the Ice Age, the ones that remain are distinct species whose disappearance would leave holes in the ecosystem.

“We’re already in an extinction, so we’re left with species that are more functionally distinct now,” he said. “There’s only a few species holding up the whole ecosystem. If we lose just a handful of species in North America, we’ll lose almost half of our remaining functional diversity.”

The researcher believes that short-term studies tend to downplay these losses by overestimating the overlap among species’ biotic functions. Still, he said, longer-term analyses of the recent fossil record provide hope by showing that some organisms can gradually evolve to occupy empty functional spaces. For instance, coyotes (Canis latrans) can adopt the ecological role wolves (Canis lupus) vacate.

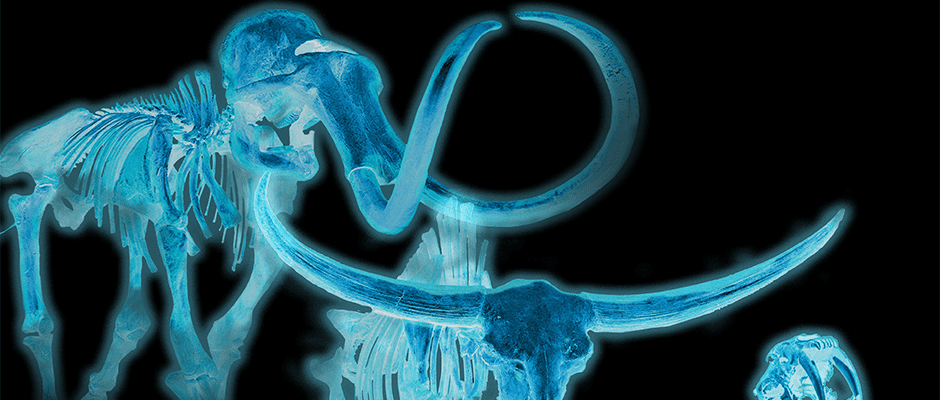

Header Image: Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), long-horned bison (Bison latifrons). ©Matt Davis