Share this article

WSB Study: How do brown-headed cowbirds pick nests to parasitize?

Brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) parasitize nests of songbirds by sneaking in, laying their eggs in the nest and watching as songbirds of another species raise the cowbird chicks as their own. Previous studies have suggested that cowbirds detect the nests that they parasitize through visual cues such as nest building activity by the host bird species, nest architectural characteristics, vocalizations of host birds and proximity of nests from a cowbird perch.

“Cowbirds are excellent at adapting, and they’re dynamic,” said Taylor Hackemack, lead author of the study published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin, who conducted the research as an undergraduate at Mississippi State University. “They’re really opportunistic. They change their egg-laying timing and they watch the hosts.”

Hackemack and her colleagues hypothesized that larger nests would more likely be parasitized by the cowbirds because the nests are easier to locate and take more time for the birds to construct, thereby increasing the likelihood that a cowbird will spot the nest.

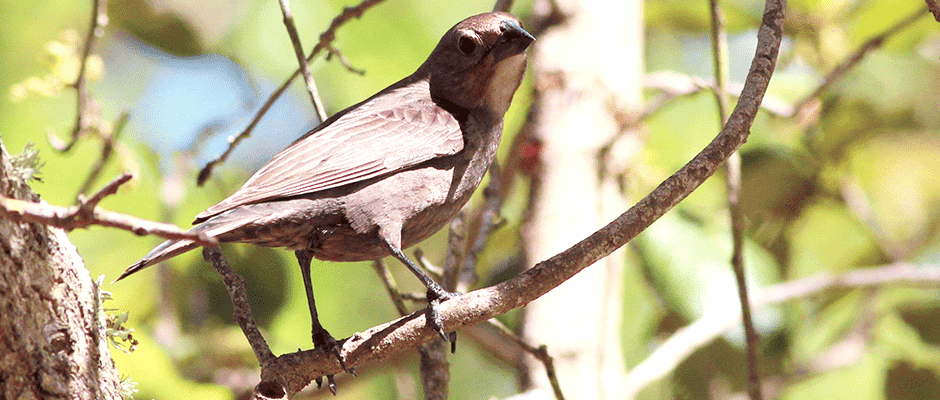

Researchers looked for nests containing cowbird eggs in shrub habitat. ©Jenny Foggia

The team collected data for the study in stands of pines owned and managed by Weyerhaueser Company in Kemper County, Miss. They looked for nests of three shrub-nesting species commonly parasitized by cowbirds: indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea), yellow-breasted chat (Icteria virens) and prairie warbler (Setophaga discolor). In this habitat, the researchers were able to easily find and monitor the nests every three to four days for predation and parasitism events. After all the fledglings left the nest, the researchers measured multiple nest size parameters — including maximum and minimum width, height, cup depth, and maximum and minimum inner cup width — and froze the collected nests in order to determine their mass later. In all, they collected 127 yellow-breasted chat, 68 indigo bunting and 30 prairie warbler nests.

After the nests were measured, Hackemack and co-author Zachary Loman used generalized linear mixed models to independently compare nest dimensions of each species to the probability of parasitism in order to test their hypothesis that larger, heavier nests have a greater probability of being parasitized by cowbirds.

But the researchers found that their prediction didn’t hold up. Yellow-breasted chats had the largest nests of the three species surveyed, but had the lowest parasitism rate at 3 percent. Indigo buntings had a parasitism rate of 18 percent, and prairie warblers — the species with the smallest nests — had the highest rate of parasitism at 24 percent.

In the paper, the authors discussed many possible explanations for the lack of correlation between nest size and the parasitism rate, such as the abundance of edge habitat in the study area. They suggest that the abundance of this habitat, which cowbirds frequently use, decreased their need to carefully choose which nests to parasitize. In addition, the study only looked at three species of birds. Many other birds also build nests in the same habitat, which cowbirds also may lay eggs in; however, these nests were less easily accessible to the team.

Given some of the uncertainties, the researchers concluded that the relationship between cowbirds and the species they parasitize are likely affected by many variables, not just nest architectural characteristics.

“The birds do more than I do in the cafeteria line to get my food,” said Hackemack. “They’re evil geniuses, really.”

Annaliese Ashley is a graduate research assistant in the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia.

Header Image: ©Gary Leavens