Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Yellow-bellied slider

- Alligator snapping turtle

WSB: Metal detectors uncover ingested fishhooks in turtles

Low-cost technology can give quick answers in field work

Low-cost metal detectors no bigger than a flashlight can help researchers detect metal fishing hooks ingested by turtles.

“I can see this being helpful when you start getting into turtles of conservation concern,” said TWS member Vanessa Lane, an associate professor of wildlife ecology and management at the Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Georgia.

Lane had long noticed a high density of yellow-bellied sliders (Trachemys scripta scripta) at Paradise Public Fishing Area, where many anglers fish. She had accidentally hooked turtles herself in the area while fishing, and wondered whether these turtles were ingesting a lot of the hooks.

Working with undergraduate students, Lane tested whether a small metal detector might be able to detect ingested metal inside these turtles.

In a study recently published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin, the team captured 426 yellow-bellied sliders and three other species. They used the handheld metal detector on all of them, waving it like a wand over their bodies. First, they wanted to see if they could detect any metal. Then, they used a more accurate instrument on the end to pinpoint the exact location of the metal in their bodies.

They got positive beeps from 37 yellow-bellied sliders from the metal detector.

“We had one turtle that had three hooks in it,” Lane said. “So, they didn’t learn their lesson.”

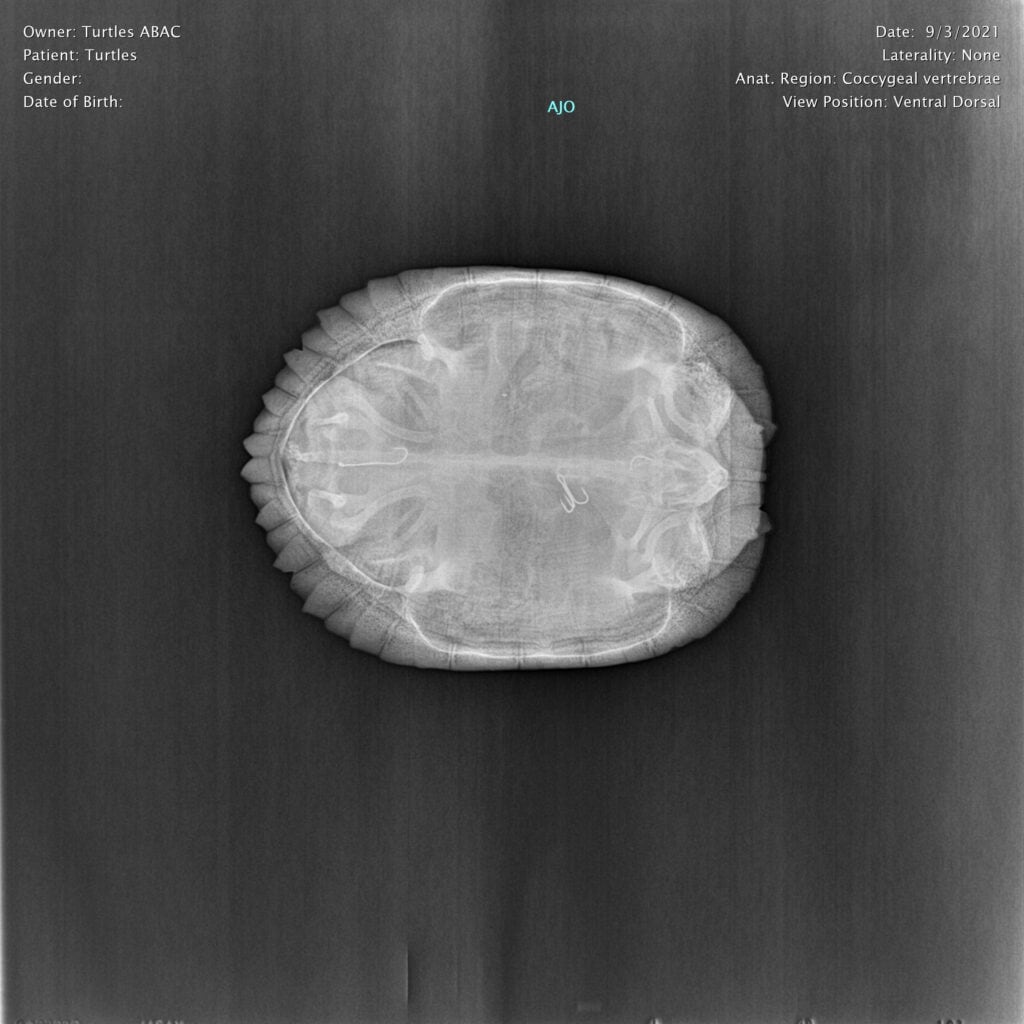

They took all of the turtles to the laboratory and ran them under an X-ray to verify whether they had ingested hooks. They also X-rayed a random sample of 69 other sliders that didn’t have a positive reading from the device.

The X-rays revealed that only five of the 37 turtles that the handheld device detected metal in were false positives—about 14%—while none that tested negative showed signs of ingested metal. Overall, this meant the accuracy of the field devices was about 95%.

“It was pretty dang cool how accurate this thing was,” Lane said.

Lane said that it’s possible that the false positives weren’t necessarily false. It could be those turtles had ingested low-density metal that doesn’t show up on the radiograph like aluminum. This means the metal detector would beep at something like the tab from a soda can, but the X-ray wouldn’t find it.

But overall, the results show that handheld, relatively cheap metal detectors can be useful for finding ingested fishhooks and other objects in turtles.

Yellow-bellied sliders aren’t in any conservation danger—their populations are unlikely to be affected by a few swallowed fishhooks, she said. A veterinarian they consulted for this study also said that most of them seemed relatively healthy—other studies on sea turtles have shown they can pass the hooks through their system. Iron can also oxidize and dissolve in animals after a period.

It’s possible that some of the sliders that ingested fish hooks died before researchers captured them, so these numbers may not represent the total amount of turtles that ingest fish hooks, Lane cautioned.

This technology could have wider applications, though—especially with species of conservation concern in the area such as alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminckii), which may be affected by ingesting the metal. Researchers might also use this with fish of conservation concern like some sturgeon species or hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis).

“I think this will work with any small animals with metal ingestion,” Lane said.

The turtles were ultimately released, since the veterinarian said that cutting open their shells to remove the hooks would likely be more harmful than the metal appeared to be inside the reptiles. However, a couple that were found with hooks embedded in their cheeks or the outside of their necks were treated.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: A yellow-bellied slider with a hook that was found stuck to the bank. Credit: Vanessa Lane