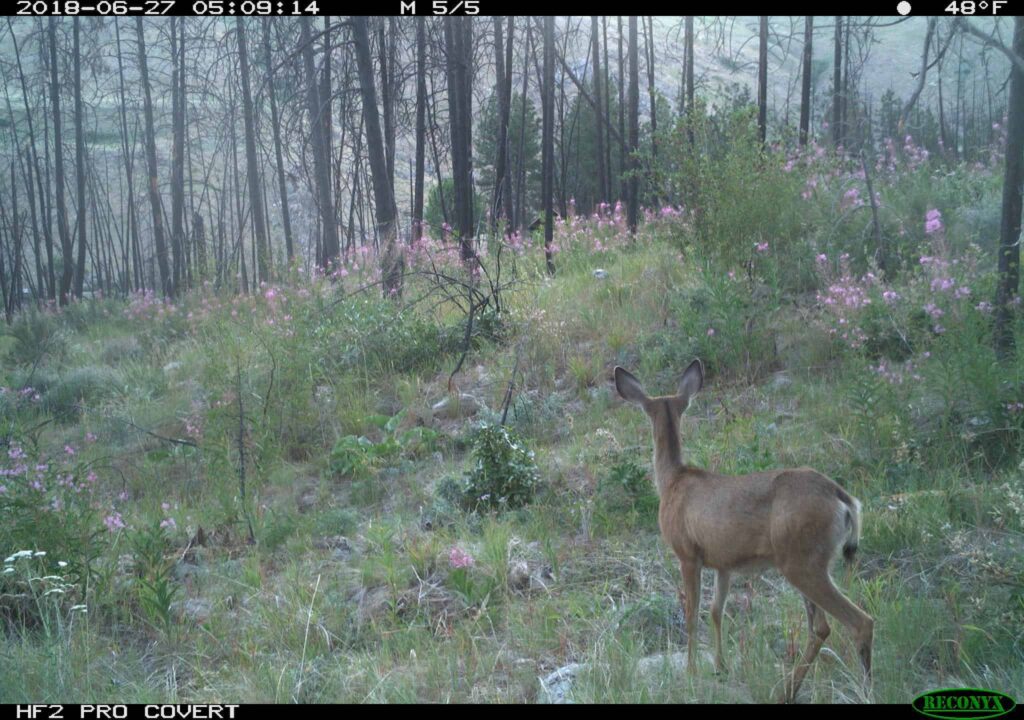

Deer may take advantage of burned forests in the summer, but they avoid burned areas with deep snow in the winter to reduce risk from the cougars that prey on them.

Fires are burning bigger and hotter in many parts of the western United States. But researchers don’t fully understand the different ways that this changes the land use patterns of deer and their predators—especially in parts of Washington state where wolves have recently recolonized the landscape.

TWS member Taylor Ganz, a PhD candidate in environmental and forest sciences at the University of Washington, and her colleagues on the Washington Predator Prey Project wanted to take a closer look at behavior shifts in the state’s north central area, which has seen “catastrophic and historic” wildfires in the last few decades.

In a study published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, she and her colleagues used data from GPS collars placed on 150 mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), five gray wolves (Canis lupus) from two different packs and 24 cougars (Puma concolor), which all used the area from 2017 to 2021.

Nearly 40% of the study area in north central Washington state has burned since 1980, while about 20% has burned since 2014. Ganz and her colleagues used the location data collected from the deer and predators and placed it into models sensitive to which areas had been burned and when.

The models revealed that in the summer, mule deer generally selected for burned areas over areas that weren’t burned.

“We think that’s because the fires tend to enhance the forage,” said Ganz, who wrote a piece in The Conversation recently about her work.

While the shrubs and bushes that grow more in burned areas also favor cougars, which typically use cover to stalk their ungulate prey, the deer are “able to manage these trade-offs in terms of predator vulnerably,” Ganz said.

But in the winter, the deer may not be as lucky. They avoided burned areas at this time, possibly because the snow is much deeper, making it harder for the ungulates to access the vegetation that they like to eat.

Forests in this area are typically defined by conifer that, when intact, tend to hold a lot of snow in the canopy. In their absence after wildfires, the snow accumulates on the ground, making for deeper snow than unburned forests.

Deeper snow also may affect deer’s ability to escape predators, since it’s harder for them to move as quickly when their hooves sink in the snow, Ganz said. Their predators, on the other hand, have large paws that act like snowshoes.

Wolves prefer more open areas when they hunt. Since a lot of shrubby vegetation tends to rise up in burned areas, this means deer use these areas as refuge from wolves.

“Unburned forests tend to be clearer in the understory because not a lot of light reaches the forest floor,” Ganz said. The data also showed that mule deer avoided areas with higher wolf pack activity in this part of north central Washington.

“Deer selected for burned areas in the summer to avoid wolves,” Ganz said.

Article by Joshua Rapp Learn