Share this article

Wild Cam: TWS Members Find What’s Eating Lemurs in Madagascar

Despite having one of the highest rates of endemism in the world, relatively little is known about animals in Madagascar. But wildlife in much of the country is suffering from habitat loss and fragmentation as forests are cut down to make way for farming. Predator-prey relations are also changing as a result of hunting and an increase in feral cats and dogs.

“Madagascar is a top conservation priority,” said Zach Farris, a student member of The Wildlife Society and an author of a recent study published in the International Journal of Primatology that attempts to estimate the population density of carnivores in the island country.

This latest Wild Cam series examines what Farris, coauthor Marcella Kelly — also a TWS member and an associate professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University — and others discovered in their camera trap study in Makira National Park in northeastern Madagascar.

Image Credit: Zach J. Farris and the Wildlife Conservation Society Madagascar Program and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

The researchers looked at three species of lemurs — the white-fronted brown lemur (Eulemur albifrons), mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) and woolly lemurs (genus Avahi ) — and, based on camera trap photos, determined whether they could predict if predators like these two ring-tailed vontsiras (Galidia elegans) were more or less likely to show up in the same area. Vontsiras, a native carnivore species related to mongooses, feed on a number of small lemurs and other species. The researchers found that the presence of carnivores like these was a good predictor of the absence of certain species like mouse and woolly lemurs.

Image Credit: Zach J. Farris and the Wildlife Conservation Society Madagascar Program and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

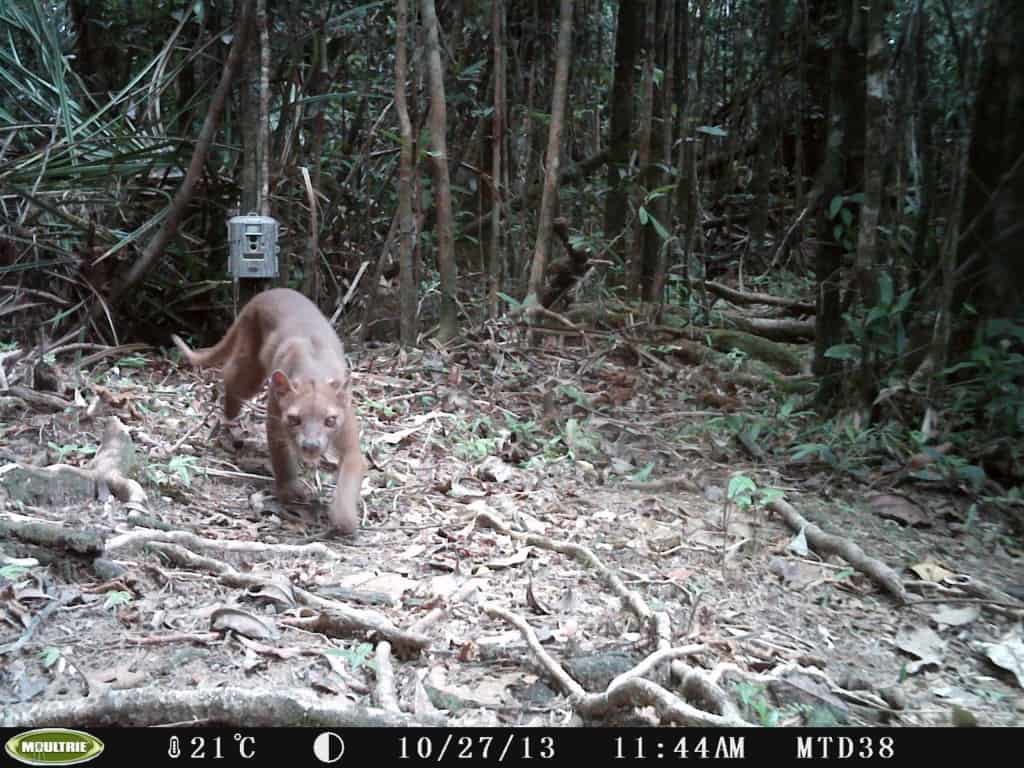

A cat carries a native rodent in its mouth. “This photo helped us demonstrate the presence of this exotic predator in this forest site and highlight their ability to successfully hunt and kill native species,” Farris said. Cats have been shown to kill and consume a number of native species from rodents and birds to tenrecs (family: Tenrecidae) and even lemurs.

One of the southernmost populations of silky sifakas (Propithecus candidus) known to exist sits in a tree. “There are believed to be less than 250 individual silkies remaining in the world and this population is facing intense pressure from an expanding cat population at this forest site,” Farris said.

Image Credit: J. Farris and the Wildlife Conservation Society Madagascar Program and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

The study showed that the country’s largest carnivore, the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox), is typically smaller than feral cats and dogs that were captured in the forest habitat. Farris also found that fossas and other native species turned up less in fragmented forests where humans and feral cats and dogs also occur.

It’s not necessarily all in the eyes when you have such a distinct territory call as the indri (Indri indri), one of the Madagascar’s largest lemur species. “This critically endangered lemur species is threatened due to forest loss, bush meat consumption, and the spread of exotic carnivores,” Farris said. “We believe its very loud calls may make it an easier target for exotic dogs and cats to locate and hunt.”

Image Credit: Zach J. Farris and the Wildlife Conservation Society Madagascar Program and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

A feral dog investigates a greater hedgehog tenrec (Setifer setosus), endemic to the island country. Farris said that dogs prey on tenrec species and lemurs. “Our work across Madagascar has shown that many native species have much lower probability of occupancy in the presence of dogs,” he said. Other species like mouse lemurs also didn’t occur where feral dogs, cats or native predators appeared in contiguous forest, showing that they may be avoiding these areas when they had elsewhere to go.

Image Credit: Zach J. Farris and the Wildlife Conservation Society Madagascar Program and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

A female white-fronted brown lemur looking alert. These lemurs were one of the few studied that avoided areas with native predators like the fossa but didn’t avoid areas with humans, feral cats or dogs. “This may demonstrate evidence of a threatened lemur species successfully avoiding native predators while failing to avoid an unknown, alien predator,” Farris said.

“The relationship between humans and dogs in this region is quite strong as dogs often travel with their owners into the forest when they travel there to work or collect materials,” Farris said. “It is believed that while in the forest, dogs are then allowed to travel freely and hunt for food. Some local people even train their dogs to assist with bush meat hunting activities, which have been shown to be widespread and prevalent across this region of Madagascar. Our research demonstrates that the presence of these dogs within the rainforest, and the local people they travel with, poses an added pressure to these already threatened and endangered lemur species occupying these forests.”

An aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis), the “world’s most bizarre and unique primate” according to Farris, using its trademark feeding technique of knocking on wood to locate insects before chewing into the bark with special teeth and using a large middle finger to scoop them out. “The aye aye is listed as endangered by the IUCN as it requires a very large home range and is threatened by forest loss and persecution by local people,” Farris said.

Overall, he says that the kind of avoidance most lemurs showed to native and introduced predators in contiguous forests weren’t as strong in fragmented forests. “As these forests become patchier and lemurs have less ability to move freely in the forest, they are encountering dogs and cats and humans a lot more,” he said.

This photo essay is part of an ongoing series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project and have photos you’d like to share, email Joshua at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Image Credit: Asia Murphy