Share this article

Wild Cam: Orcas to blame for Aleutian sea otter collapse

Many people thought the sea otter populations around the Aleutian Archipelago were the model of the species’ success. For decades, populations up and down the Pacific Coast of North America blinked out due to past exploitation in the fur trade. But sea otters in parts of the Aleutian Islands, an archipelago stretching from the Alaska Peninsula off the southwestern end of the state all the way to Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, were relatively insulated from fur trade harvesters due to the remoteness and inhospitable nature of the area.

By the 1990s, the trade of sea otter fur collapsed, in large part because the animals became extirpated in many areas. In some places, the otters slowly began to recover, though it wasn’t until translocation efforts from 1968 to 1971 that the sea mammals once again swam in the waters of places like coastal British Columbia, Washington state and southeastern Alaska.

“The first places where sea otters recovered to equilibrium abundance were in the Aleutians,” said Tim Tinker, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Tinker followed the Aleutian population of sea otters (Enhydra lutris) for decades while working with the U.S. Geological Survey. In the early 1990s, Tinker, University of California, Santa Cruz colleague Jim Estes and others compared the recovering population in California with those of the Aleutians, which they believed were stable.

Enlarge

Credit: Gena Bentall

But halfway through the decade, the bottom fell out on the population of Adak Island, an area of the Aleutians Tinker and Estes were conducting fieldwork in.

“I really think something is going on, the population seems to be crashing,” Tinker wrote at the time to Estes. “At first he thought I was probably crazy.”

Enlarge

Credit: Tinker et al. 2021

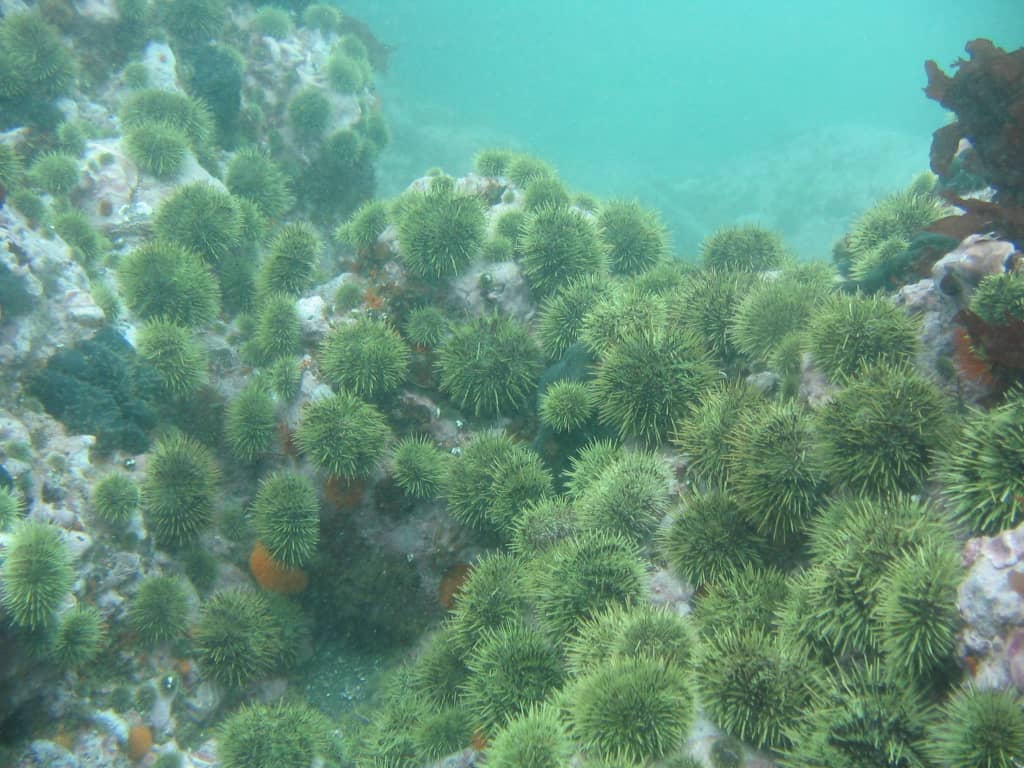

More proof of the otters’ decline came when sea urchin population exploded in abundance in areas off Adak Island like Sweeper Cove and Bay of Islands. Sea otters prey on sea urchins, but when the mammals aren’t around to harvest the spiky creatures, urchins can tear through entire forests of kelp, changing the ecosystems in the process.

Researchers wondered if chemicals may be the culprit of the otter decline. The U.S. Navy, one of the funders of a study on sea otter population conducted in 1995-1996, had been interested in tracking the effect of harmful chemicals—PCBs—in the ocean. The Navy had buried barrels of the chemicals, which had various uses in appliances, electronics and other devices, in the area after World War II, and some of these drums and other sources of PCBs had begun to leak into rivers on Adak.

“The islands are quite small, so everywhere drains into the ocean,” Tinker said.

Further surveys showed the contamination was limited to a few small areas such as Sweeper Cove, and sea otters weren’t just disappearing there.

“We soon realized this was, in fact, a decline that spanned multiple islands, and by the late 1990s we determined that it affected the entire Aleutian Archipelago,” Tinker said.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Murray

By accident, Tinker and his colleagues stumbled upon their first clue about what was really causing the decline. The team’s veterinarian The team’s veterinarian, Carolyn McCormick, had to cut a capture and tagging trip due to a family emergency. To make best use of the last few days, Estes and Tinker and team tagged animals in Clam Lagoon, an estuary formed by two terminal glacier moraines, which was closer to the airport on Adak Island. The 100-odd sea otters living in the Lagoon were almost entirely isolated—they would later discover it was a distinct population from other Aleutian animals, feeding entirely on clams rather than urchins. The Clam Lagoon otters even lack the distinctive purple teeth most of the species has due to their urchin diet.

Enlarge

Credit: Keith Miles

Tinker and his colleagues, captured, measured and tagged otters there. The last-minute change of plans proved lucky—the surveys revealed that the Clam Lagoon population was the only one that wasn’t declining.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Kenner

Meanwhile, Tinker and his colleagues had seen killer whales (Orca orca) preying on sea otters off the coast in other areas—attacks they initially thought were just curiosities. In areas where orcas would normally target harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) or Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus), the whales were seen ducking right into kelp forests that had previously provided safe harbor for otters, killing and consuming several of the animals.

But the Clam Lagoon otters were protected from killer whales—the unique geography of the lagoon blocked orcas from getting into the area.

Tinker, Estes and colleagues hypothesized this may be the cause of sea otter declines in the late 1990s, and Estes and others even speculated that the whales may be causing Steller sea lion declines.

Enlarge

Credit: Tinker et al. 2021

The researchers realized they needed to take a more comprehensive look at the issue, since any number of other problems, like disease or starvation, could have played a role in causing such a major drop.

In a study published recently in Ecological Monographs, they gathered decades of data from multiple field studies, including sea otter behavior and dietary data, necropsies on sea otter carcasses washed up on the beaches of the island, as well as abundance and distribution data from aerial and skiff surveys. Radio-tagging operations and capture-recapture surveys also gave them information on body condition and size. Blood samples revealed information about their health. Scuba surveys also gave them an idea of sea urchin and kelp abundance.

Enlarge

Credit: Tinker et al. 2021

The patterns that emerged after combining these data gave researchers a clear picture of what was causing the decline of Aleutian sea otters. A model comparing the possibilities of decline revealed an 80% chance that predation was the culprit. Other factors like chemical contamination, disease or climate change only had a 30% chance at most for being the main driver of decline.

“It’s not that we have a smoking gun, but we have a Bayesian type smoking gun,” Tinker said, referring to the type of model analysis used to predict uncertainty in his study. He added that it’s possible other predators in addition to killer whales, like Pacific sleeper sharks (Somniosus pacificus), could also eat otters, though this has never been observed. “We’re now on firmer ground saying that predation remains the best supported hypothesis.”

Statistical models on orca energetics revealed sea otters likely don’t make up much of the whales’ diets. The otters just aren’t big or numerous enough to play a major role in keeping killer whales healthy.

Enlarge

Credit: Gena Bentall

On the other hand, a moderate number of killer whales only ometimes preying on sea otters can have a big impact on otter populations. While it wasn’t part of Tinker’s paper and just a single example, he said a necropsy of a killer whale at Bering Island recently revealed it had seven sea otters in its stomach. “And they had all recently been eaten,” Tinker said, adding that more work still needs to be done to determine which orca pods might be responsible, and how often they are consuming otters. But researchers are closer to a solid answer for the decline of a once stable population of sea otters.

“Understanding the causes of this type of large-scale decline is really important for a broader understanding the drivers of ecological change,” Tinker said.

Enlarge

Credit: Tinker et al. 2021

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Killer whales swim through a kelp forest in the Aleutian Islands. Credit: Mike Kenner