Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- moose

- gray wolves

- brown bears

- wolverines

Wild Cam: How does injury affect moose movement patterns?

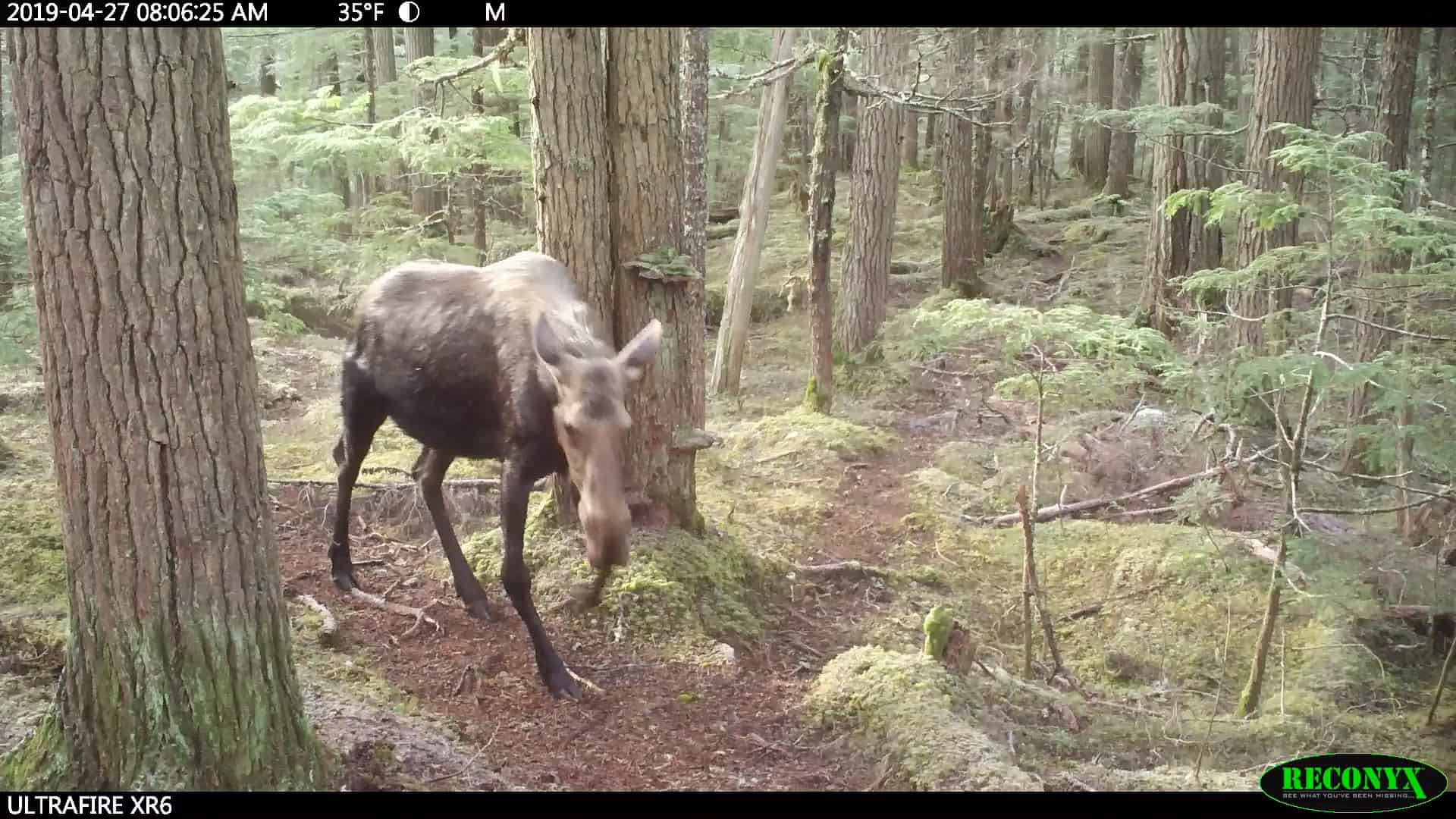

Researchers captured videos of injured moose using game trails in northern British Columbia

Andrew Hendry had been putting up trail cameras for years along a game trail near his cabin that sits close to the Skeena River in northern British Columbia. During the COVID-19 lockdown, he began going through the camera footage and noticed a fair number of injured moose moving up and down the trail.

“It’s painful to watch them walking,” said Hendry, a professor at McGill University in Montreal.

In some cases, he saw the same individuals going past multiple cameras on multiple occasions—something that surprised him as it seemed to go against the typical biological theory that injured animals would be weeded out of the population.

And it’s not like there were a lack of predators around—the same cameras captured 476 instances of gray wolves (Canis lupus) and 224 instances of brown bears (Ursos arctos horribilis) on top of the 2,966 instances of moose (Alces alces).

In a study published recently in Ecology and Evolution, he examined the footage gathered over three years to learn more about how injured moose manage.

He and his co-authors, who included his teenage daughters, found that, in general, moose used these trails for travel rather than foraging. They moved to lower elevations in the fall and winter, and back upward in the spring—kind of like a mini-migration.

Moose sightings were clumped into clusters—on some days Hendry would capture footage of dozens moving past cameras, while on intervening days, no animals turned up at all.

The researchers identified 12 different injured moose over this period. Categorizing the injuries with the help of veterinarians and zoologists, the team found that most were ankle injuries, though there were also some leg injuries, as well as missing ears or eyes, and cuts.

The ankle and leg injuries varied, but all the animals were still walking. Some of them had their ears down in the footage, which Hendry said could indicate they’re in pain.

However, the injured animals didn’t show any difference in the way they used the trails. They still went in the same direction and at the same rate as non-injured moose.

“At least for this part of the trail, they have found a way to deal with their injury that doesn’t compromise their movement,” Hendry said. “We even have some videos of them running.” And in a few cases, Hendry said, it appears as if the same injured moose cross the same cameras in multiple years.

In retrospect, this discovery was unsurprising, Hendry said, because if they couldn’t still move normally, they would have a higher chance of being killed.

The number of wolves they captured on camera indicated that there was still plenty of danger around—the pack is sometimes 15 strong. And the moose use the same trails as the wolves, traveling up and down half a dozen times per year.

“This is not a happy stud farm in the sky,” he said. “This is a place where [the moose] are going to have challenges.”

The footage sometimes reveals the danger in lucid detail. After wolves are seen walking the trail, the moose are often running for the next day or so.

The cameras even captured wolverines (Gulo gulo) a few times. “They are just kind of loping all the time looking for dead animals,” Hendry said.

The fact that some injured animals are seen on cameras doesn’t necessarily disprove that the weakest aren’t weeded out, the authors of the study noted.

“The most straightforward explanation might be that moose with particularly debilitating injuries died before we recorded them,” the authors wrote. “That is, only individuals whose injuries did not dramatically compromise locomotion—at least not for a long period of time—were able to survive and thus be recorded by our cameras.”

It’s also possible that the injuries affected the moose’s mating ability, calf-rearing or long-term survival. But more comprehensive research would be needed to learn more about these potential effects, the authors said.

Just how the moose acquired their injuries is unclear. Some camera footage shows individuals tripping over logs and other objects. But they seem to recover fine—as seen in Hendry’s “Moose Fails” compilation above. He’s been uploading footage like this onto his TikTok and Instagram accounts, which have become quite popular.

For now, Hendry’s cameras are still running. In more recent winters, he’s noticed even more moose injuries, as well as animals that appear starving or thin for the time of year. He’s not yet sure why, but he said it’s possibly climate related.

Header Image: A moose captured on camera with an injured ankle. Credit: Andrew Hendry