Share this article

Wild Cam: How Airplanes Ruffle Plover Feathers

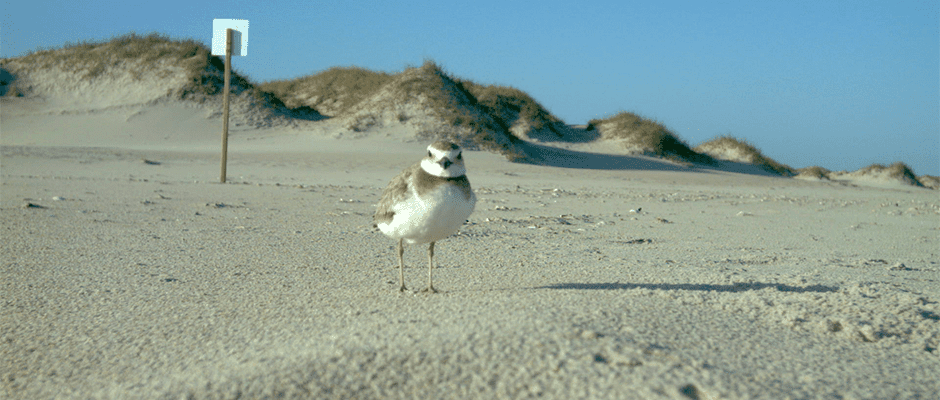

Wilson’s plovers (Charadrius wilsonia) would probably do well with a little peace and quiet when incubating their eggs — whether from natural predators, humans, vehicles and, according to recent research, aircraft.

The U.S. Marine Corps base in Cherry Point North Carolina — a large base that constantly flies military jets over the ocean — funded research to determine if their overflights are interfering with incubating plovers and other shorebirds. Currently, the National Parks Overflight Act of 1987 Act prevents the U.S. Marines from flying their aircraft at a certain speed and height over national parks, and they had been seeking permission from the Federal Aviation Administration and National Parks Service to ease some of those restrictions.

As part of a recent study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management and featured in this Wild Cam series, researchers at Virginia Tech University including lead author Audrey DeRose-Wilson recorded audio and visuals of Wilson’s plovers at Cape Lookout National Seashore in North Carolina in order to observe their heart rate and behavioral changes before, during and after overflights occurred.

As part of their study, DeRose-Wilson and her colleagues built and used unique equipment to record the birds’ heart rates. DeRose-Wilson inserted a button-sized microphone into a plastic craft egg in order to pick up the frequency range that a heart rate would fall into. Next, they used a digital voice recorder to record the sound and buried it in the sand a few feet from the nest. To waterproof the craft egg and to protect the microphone, they stretched Parafilm over the egg. “[The plovers] readily accepted the fourth egg in their nest,” DeRose-Wilson said.

A plover watches alert as a civilian Bell Helicopter passes overhead. Plovers rarely leave their nests, even when disturbed by aircraft flying above them. As a result, the researchers monitored the birds’ behaviors in other ways. For example, sometimes the plovers exhibit an upright posture and flatten their feathers down while stretching out their neck when they sense danger. Other times they flatten out in an “alert crouched posture” maintaining stillness and alertness.

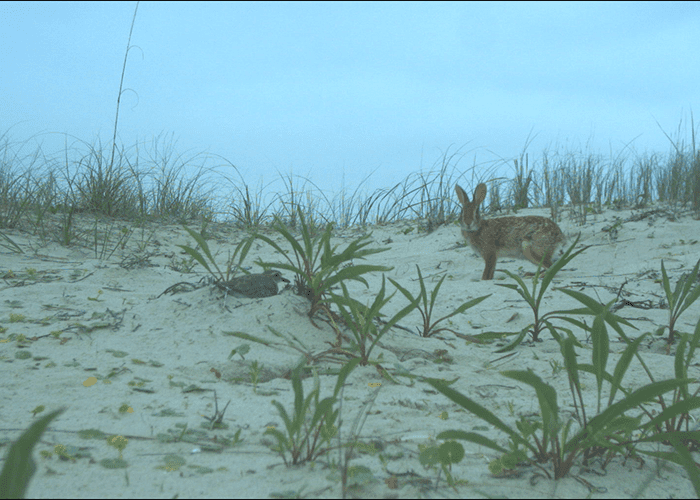

This incubating Wilson’s plover crouches alert as an eastern cottontail passes its nest.

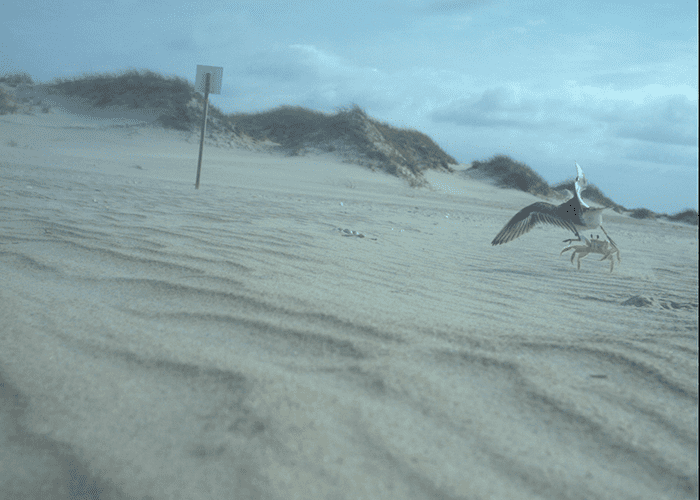

Throughout the study, DeRose-Wilson and her colleagues observed other predators approaching plover nests as well. This Wilson’s plover defends its eggs from a ghost crab. While ghost crabs (Ocypodinae) typically eat plover eggs or chicks whenever possible, in this study the Wilson’s plovers were usually able to ward off these predators.

However, when it came to other predators, plovers weren’t always as fortunate. In this photo, a fish crow (Corvus ossifragus) steals a Wilson’s plover egg away from its nest. Crows often carry the eggs off to a nearby perch to eat them.

A raccoon tries to gnaw on the fake egg, which researchers used to monitor plover heart rate. Raccoons and crows were the primary nest predators at the researchers’ study site.

DeRose-Wilson also caught the plovers performing some inexplicable acts in the sand. “This is one of my favorite photos from two years of camera traps at plover nests,” DeRose-Wilson said. “I have no idea what the plover is doing!” Some of her guesses: Plover yoga? A somersault? Maybe it’s important for them to stretch their legs occasionally to keep limber while incubating, she said.

An incubating Wilson’s plover watches a turboprop military transport plane (Lockheed C-130 Hercules) fly overhead. DeRose-Wilson said aside from aircraft, the birds constantly respond to other potential sources of disturbance such as humans and vehicles.

DeRose-Wilson and her colleagues found that while the birds’ heart and incubation rates didn’t change during overflights from helicopters or civilian fixed-winged aircrafts, the birds did exhibit more alertness during military rotary-wing overflights and more scanning behavior during both military and civilian fixed-wing overflights.

“We didn’t recommend the flight ceiling be raised for the marines,” DeRose-Wilson said. “But it did alert us that yes, the birds are responding to the stimuli. We need to assess where the threshold is that we would assess it as a real problem.”

DeRose-Wilson also said that while she studied Wilson’s plovers, it is possible that the results of her study could also apply to the federally endangered piping plover (Charadrius melodus). “There’s a lot of evidence in the literature that shows that age and reproductive cycle play a role in response to disturbances,” DeRose-Wilson said. “You might be able to apply this study to breeding piping plovers, but perhaps not plovers in different parts of the reproductive cycle.”

This photo essay is part of an ongoing series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project and have photos you’d like to share, email Dana at dkobilinsky@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Image Credit: Audrey DeRose-Wilson