Share this article

Wild Cam: Costa Rica’s black panthers and elusive bush dogs

Ongoing research using trail cameras in Costa Rica’s mountains has revealed the presence of elusive bush dogs as well as why some populations of large felids, like tiger cats and jaguars, might more often have black coats.

The discovery of bush dogs in the Central American country “is definitely something new under the sun,” said TWS member Mike Mooring, a biology professor at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego. “They are amazingly elusive throughout their whole range.”

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

Mooring and his students worked with a large group of local partners from communities across Costa Rica out of the Quetzal Education and Research Center run by Southern Nazarene University. They began running camera traps in 2010 in the Talamanca Mountains, which roughly run from San Jose southeast to the Panamanian border and continue into Panama. The researchers hoped to learn more about the country’s cloud forest mammal communities, but they also wanted to get local people more involved and interested in the wildlife around them through community-based conservation.

Several studies have been published using the data collected from these cameras, which now number well over 100 permanent camera stations. The papers vary from describing trends in the occurrence of melanism in jaguars (Panthera onca) and northern tiger cats (Leopardus tigrinus), to the first discovery of bush dogs (Speothos venaticus) in the expansive La Amistad International Park, secretive canids normally thought to be found only in South America and Panama. They also describe trends in how moonlight affects predation risk and how circadian activity can predict predator-prey interactions of elusive mammals.

The term black panther is loosely used to describe melanistic cats, but the truth is they are not always completely black. Many still have visible darker spots or rosettes on their coats. The research on these cats reveals findings contrary to previous thinking. Researchers typically believed that the appearance of melanism in tiger cats or black jaguars, such as the one above eating a Baird’s tapir (Tapirus bairdii) carcass, was mostly due to chance genetics unrelated to natural selection.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

But observations of black tiger cats, pictured above, and jaguars on the trail cameras revealed there was a pattern in the Talamanca Mountains. For starters, researchers found that jaguars and tiger cats were much more likely to be melanistic than other felids, like ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) or pumas (Puma concolor), in the area. Black cats were also found more often in dense forest, where their coats may be better camouflaged in the dim light compared to more open areas. Some 25% of jaguars found in dense forests in the area were melanistic, and about a third of the tiger cats recorded were also melanistic and found in cloud forests.

“People have thought melanism is random, but it doesn’t seem that way,” Mooring said.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

They also found that the melanistic individuals were more active during the day compared to cats with more common spotted or rosetted coats, which were more active during darker periods at night or during dusk and dawn. Mooring said these results imply that natural selection favors melanism and that the black panthers enjoy the advantage of being more cryptic during the brighter periods over other jaguars and tiger cats.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

The photos of bush dogs in La Amistad International Park near the Panama border, like this female with two pups, emerged along with independent records from two other projects in other areas. Undocumented sightings of bush dogs from area residents had previously been reported, Mooring said, but these photos were among the first to provide incontrovertible proof of their existence in Costa Rica.

Bush dogs are known to occur in packs consisting of a single mated pair and their immediate family, but little else is known about them, Mooring said. Due to their elusive nature, it’s unclear whether sparse populations have long been present in Costa Rica but were seldom detected or whether they are new arrivals expanding their distribution from South America.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

Photos have also turned up other canid newcomers: coyotes (Canis latrans). The Savegre Valley may have the highest concentration of coyotes anywhere in the country. Camera traps there have more photos of coyotes than of any other animal, often occurring in groups of two or three individuals.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

According to local residents, the coyotes moved into the Savegre Valley from the north in the 1960s due to their ability to tolerate the deforestation and development taking place in the valley. But in more recent years, most areas in the valley have reverted back to forest, yet the coyotes remain. Mooring worries that coyotes, which have now dispersed southward to the Darien Gap connecting Panama to South America, may outcompete native felid predators that are similar in size, prey choices and activity patterns.

“It suggests that maybe they could displace ocelot, which we don’t see a lot where we are, or other equivalents in the predator guild,” he said.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

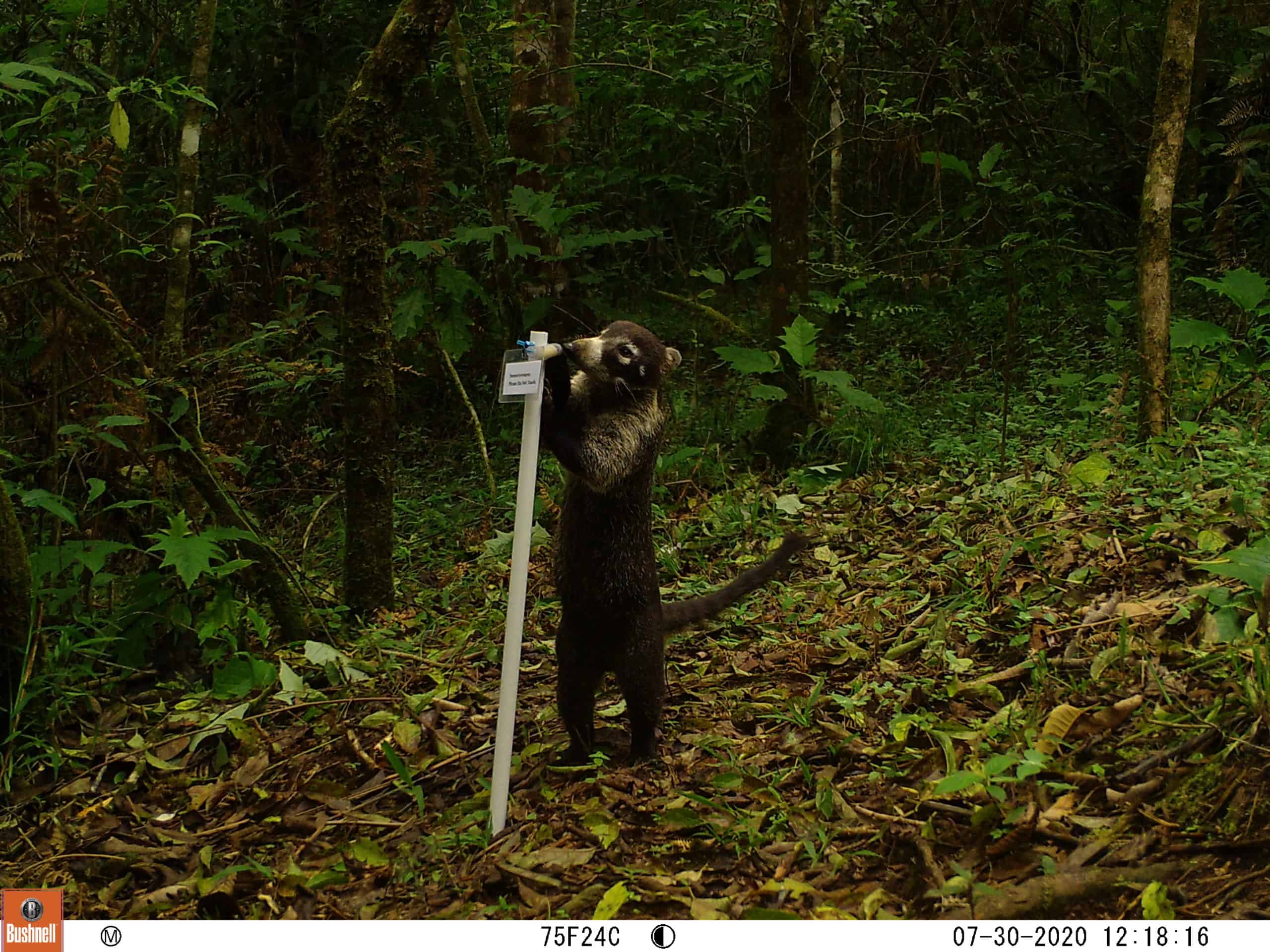

The researchers used a scent lure in front of the cameras to attract mammals like the puma pictured above. They’d heard from other research that Chanel No. 5 was very effective, but the perfume was a little too expensive. They used Calvin Klein’s Obsession for Men instead, which has an artificial aroma mimicking the scent of civets, and found it also worked very well.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

“Coyotes go crazy — they love it,” Mooring said, but jaguar, pumas, white-nosed coatis (Nasua narica), pictured above, and many other species were also attracted to the scent.

Enlarge

Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

The researchers have also found other patterns concerning mammals in the area. The photos have helped them develop a better estimate for jaguar numbers. Previous estimates had put the number at around 500 indivuduals in the Talamanca Mountains of Costa Rica, but recent studies have estimated no more than around 70.

“The population numbers have gone down as we get a better idea of what’s going on,” he said.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

They’ve also seen some evidence that jaguars and pumas may be in competition, as areas with many jaguars do not have as many pumas as areas with few jaguars. This work hasn’t yet been published.

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

Aside from helping conduct the research, involvement by community members fulfills another role of educating locals about the rich ecology around them, Mooring said. The project employs community volunteers to check and maintain the cameras, often national parks staff that otherwise would not have the opportunity to participate in research. Community members are empowered to participate in conservation research that would otherwise be impossible due to limited staff and budget of protected areas. Photos of the wildlife around them are often shared via social media or at community presentations, and Mooring said people are often surprised by just how many species are nearby their homes.

“It has a galvanizing effect on the community when they see photos of animals they don’t normally see,” Mooring said. Many species are elusive or only come out at night. “Even if you’re a local and you’ve lived there all your life, you may never or only rarely see these animals.”

Enlarge

Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project

The camera trap work is ongoing in the area, as well as other work like scat collection aided by detection dogs, like the one pictured above perhaps appropriately named Tigre. The researchers are working with Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization, to collect genetic information from the scat samples to improve distribution data on pumas, jaguars and other felids, and to better understand population barriers and movement.

Header Image: A melanistic jaguar peers at a camera trap. Credit: Mike Mooring / PLNU-QERC large mammal research project