Share this article

Wild Cam: California condors take over the carcass buffet

Watch out, golden eagles—a new scavenger is moving into southern Utah, and it might affect your meal ticket.

California condors were extirpated from Utah, and from most of their range in the U.S., in the 1900s due to lead poisoning and persecution in the form of unregulated hunting.

The birds returned to northern Arizona in 1996 due to captive breeding and reintroduction. They nested in the Grand Canyon and surrounding area, growing to a population of 115 birds today.

Enlarge

Credit: Anne-Laure Blanche

California condors (Gymnogyps californianus) don’t hunt live prey. They only scavenge carcasses, finding them by vision alone—the birds have a poor sense of smell. Wildlife managers still feed them carcasses around their release sites in Arizona, but condors can fly hundreds of miles in a day while searching for more carrion. As a result, the population began to expand into southern Utah.

TWS member Anne-Laure Blanche wanted to see what kind of effects their return would have on the scavenger community around the Cedar Mountain plateau near Cedar City in Utah.

“Reintroduction can have consequences for food chains and entire ecosystems,” said Blanche, a master’s student at Utah State University.

Enlarge

Credit: Anne-Laure Blanche

In preliminary research presented at The Wildlife Society’s 2022 Annual Conference in Spokane, Blanche described how she and her colleagues placed carcasses at eight pastures around Cedar Mountain, then aimed trail cameras at them to observe scavenger behavior. They noted the characteristics of the surrounding habitat and the carcasses themselves. Then, they visited the carcasses every other day to check the cameras and track decomposition.

Enlarge

Credit: Anne-Laure Blanche

The trail cameras revealed a number of native scavengers visited the carcasses, including black bears (Ursus americanus), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) and turkey vultures (Cathartes aura). In this presentation, Blanche examined the effects of condor presence on the behavior of golden eagles and turkey vultures.

In the study area, condors show up where there are domestic sheep on the plateau, which have a relatively high death rate, during the summer.

“Condors are pretty tightly linked to the sheep community here,” Blanche said.

Enlarge

Credit: Anne-Laure Blanche

Before they even checked the cameras, the researchers looked for telltale signs of individual scavenger use. If bones were picked clean, or hides turned inside out, for example, it often meant condors had been there. Large feathers at the scene of the feast also indicated condor presence. Golden eagles, like one pictured above, typically scattered tufts of wool around the carcass site.

Turkey vultures didn’t leave as many unique signs behind, so Blanche really only knew they had been there by seeing them flush from the site when she and her colleagues arrived.

Once the team analyzed the trail camera footage, they learned a lot more about these relationships. When condors showed up at a carcass, eagles and vultures wouldn’t hang around too long—they typically left within eight minutes.

“The way that condors would usually kick off a golden eagle is by running at it with their beak open,” Blanche said.

It also took about an hour for the first condor to show up once another scavenger species had found the bounty. They usually polished off the carcass pretty quickly, Blanche said

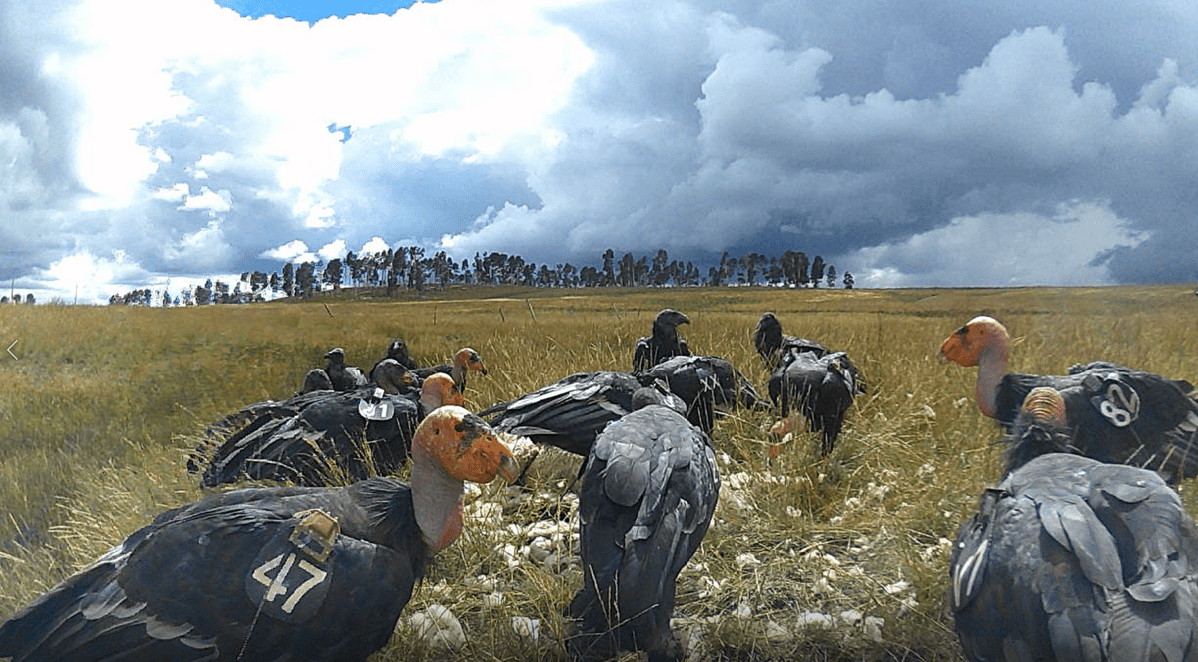

When the eagles and vultures were gone, the condors ate in harmony, though. “Condors are gregarious so they will feed together,” Blanche said. Sometimes there were more than 50 condors on one carcass, though the average was 14.

Enlarge

Credit: Jon Myatt, USFWS National Digital Library

Condors typically fed in grasslands areas—this is partly because with a nine-foot wingspan, they need a lot of space to take off after landing. But other than that requirement, they were ubiquitous, feeding on whatever they can find, Blanche said.

Enlarge

Credit: Anne-Laure Blanche

Blanche, pictured above, said that the arrival of condors in the area probably will affect the feeding strategies and resources of some of the other scavengers in the community. Some wildlife may have to turn elsewhere for food due to the arrival of these large newcomers.