Share this article

TWS2021: Old bison horns can reveal lost ecological information

Long before wildlife managers struggled to translocate bison to new areas in an effort to recover lost herds, the giant bovines wandered across vast stretches of North America. While most people associate large herds of bison with the Great Plains in the West, bison bones and fossils have been found in a diverse array of ecosystems, from Florida, to California, to Alaska.

Researchers are now analyzing these bones to get a clearer idea of the diets that once sustained bison. They hope this information can help them uncover what areas bison (Bison bison) can be reintroduced in the future.

TWS member Darian Bouvier, a master’s candidate at East Tennessee State University, analyzed seven bison horns that were hundreds of years old to uncover information about bison diets. Bouvier presented her findings on a poster at The Wildlife Society’s virtual 2021 Annual Conference.

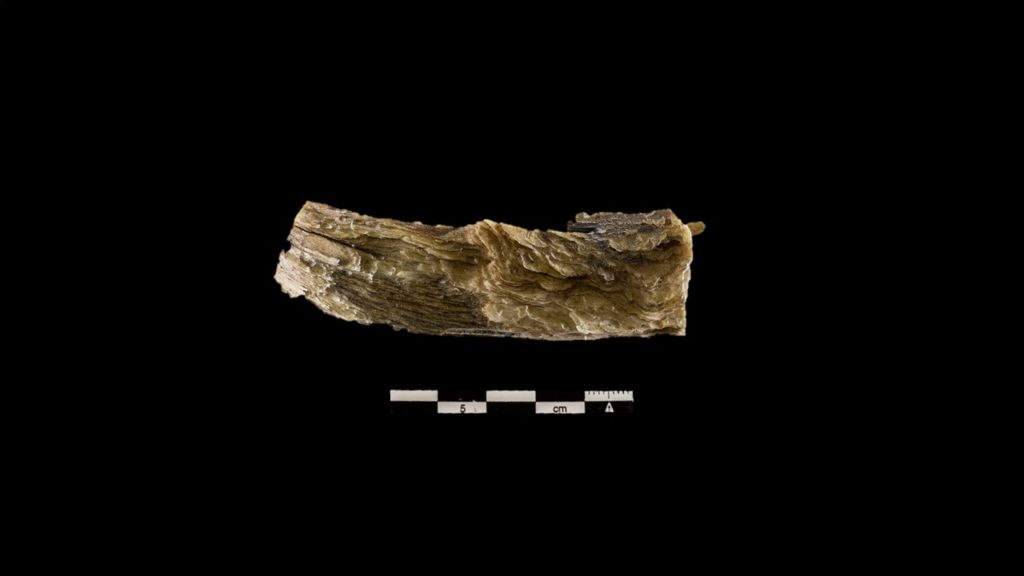

A bison horn sheath found at an elevation of 3,310 meters Credit: Matt Harrington, edited by Darian Bouvier

Bouvier examined the sheath of the horn, or the outside shell that isn’t preserved in the fossil record as often as the bony interior. One of the only places the sheaths are preserved well is in ice—they are sometimes found in high altitude glaciers as they melt.

Researchers can study these sheaths that preserve information about the animals’ diets over time. Different layers of keratin in the sheaths have different stable isotope ratios. These stable isotopes can be matched to plants, giving researchers an idea of the types of grasses the bison were eating, or how much water was around, Bouvier said. Over time, the different layers in the keratin can give a dietary chronology of the long-dead animal.

“It’s an opportunity to use something that’s not so common in the fossil record,” said Chris Widga, head curator of the Gray Fossil Site and Museum at East Tennessee State University. Widga was Bouvier’s supervisor for this research.

The horns they examined were found in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—two of them in high elevation icy patches.

A subsample taken from the previous image, with the outmost layer showing.

Credit: Matt Harrington, edited by Darian Bouvier

The research is still preliminary, but the sheaths have begun to reveal that in the past, what bison ate and where depended on the seasonal and regional availability.

Another thing that has stood out so far is that many of these bison were living at higher altitudes than remaining herds today.

This research can help scientists understand more about what constitutes the ecological niche the bovines can occupy. Bouvier said this is important because it will help ecologists home in on the areas that might benefit from the reintroduction of these ecosystem engineers.

“The more we learn how to coexist with those thriving ecosystems, the better it can be,” Bouvier said.

Header Image: Bison gathered in Lamar Valley, Yellowstone National Park. Credit: Matt Harrington