Share this article

TWS2020: How mammals avoid getting caught sleeping

When it comes to surviving in the wild, sleeping undisturbed is a major challenge. But ongoing research explores some of the diverse strategies that mammals have adapted to keep themselves from snoring their way into becoming prey, from keeping half their brains awake, to using a midnight hideaway, to sleeping close together in groups.

“[Anti-predator behavior during sleep] is a really exciting new field of research,” said TWS member Ishana Shukla, an undergraduate student at University of California, Santa Cruz, who presented her ongoing research on a poster at The Wildlife Society’s virtual 2020 Annual Conference.

Shukla was interested in looking at how different species interact with each other when she learned that little research had been done on wildlife sleeping strategies. While some scientists had examined how individual species sleep, nobody had looked at the overarching trends of how animals protect themselves at their most vulnerable moments.

Shukla and her colleagues examined 230 papers that covered sleeping mammals, including everything from the way sleep evolved in different species to when they sleep and physiological research on sleeping animals. These studies covered nine mammalian orders, including ungulates, cetaceans, rodents, primates, bats and others.

A brown bear taking a nap on a log. Credit: C Watts

The team found that while strategies for recharging varied greatly among mammals, they could be divided into four overarching categories — though many animals use more than one of these strategies while snoozing.

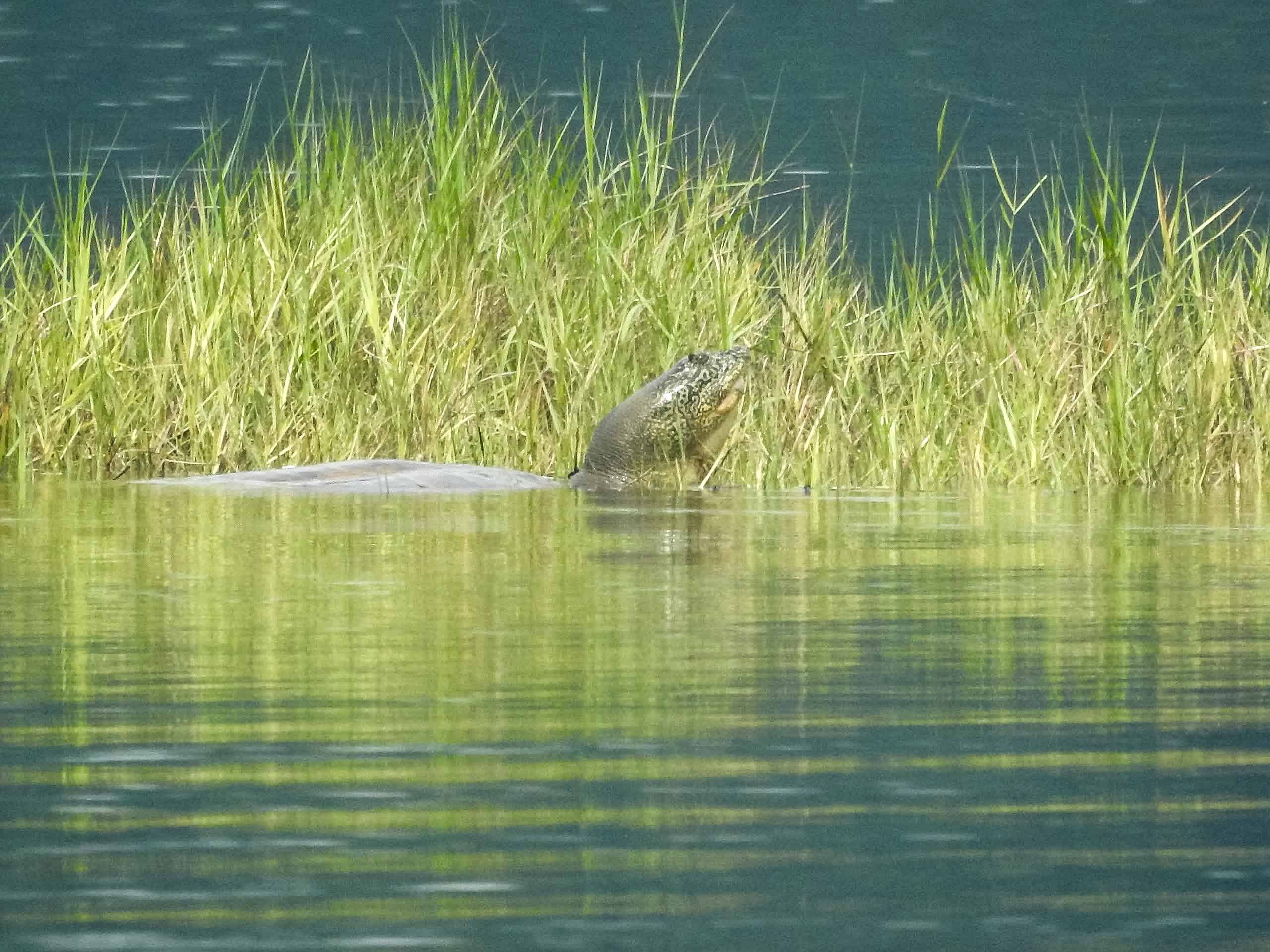

The first involved specialized forms of sleep. Dolphins and seals, for example, have evolved to essentially sleep with one eye open or at least keep one side of their brain turned on. These marine mammals can turn off one half of their brain at a time, leaving the other side alert to keep an eye out for predators in the ocean.

On land, some ungulates have developed a specialized strategy, where they have largely suppressed their need for sleep, minimalizing it to a few hours a day, Shukla said.

A second major strategy involves sleeping when predators are active. If lions (Panthera leo) mostly hunt during the daytime, for example, prey may be better off sleeping during these hours, since they are less visible.

The latter strategy often works in tandem with the third strategy: hiding. Shukla said that this could include sleeping in burrows dug into the ground, nests or high up in the trees. In the Simien Mountains, gelada monkeys (Theropithecus gelada) have adapted to sleeping on cliffsides where predators like Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis) can’t reach them.

The fourth strategy Shukla and her colleagues laid out is a group sleeping strategy where some animals go to sleep while others — of the same species or sometimes of different species — keep an eye out for danger. Giraffe herds for instance, form a circle around sleeping animals while those on the periphery keep watch.

Shukla and her colleagues also examined some of the ecological drivers of these sleeping strategies.

Evolutionary history was a major driver. Large ungulates like moose (Alces alces) or giraffes aren’t capable of digging burrows large enough to take a nap in, so these animals need to adopt different strategies.

Environment also plays a major role. Mammals that spend their time in riskier, more visible ecosystems like savannas or the open ocean have fewer places to hide. That’s where strategies like sleeping in groups or turning off half their brain comes in.

Another consideration is where the sleeping mammal sits in the food web. Herbivores, like ungulates can eat vegetation at any time of day, so they may be able to sleep at more strategic times to avoid predators. But other mammals may need to be awake when their prey are active. Apex predators also have fewer challenges than mesopredators, Shukla said, since large carnivores don’t need to balance the need to eat against the danger of getting eaten.

All of these strategies could also be affected by human disturbance. Even apex predators might not get the same easy slumbers when faced with relatively recent factors like the light pollution, noise from traffic or other problems while limited resources from habitat loss may result in changing sleeping patterns.

“If you limit the amount of resources, that actually shifts the timing of sleep,” Shukla said.

With so little research done on wild resting animals in general that we know very little about how this may affect wildlife. But in Shukla’s opinion, “Human disturbance is changing sleep.”

This research was presented at TWS’ 2020 Virtual Conference. Conference attendees can continue to visit the virtual conference and review Shukla’s paper for six months following the live event. Click here to learn about how to take part in upcoming conferences.

Header Image: Mammals have developed a number of strategies to snooze without getting eaten. Credit:Malcolm Cerfonteyn