Share this article

TWS salutes women in wildlife biology careers

The National Women’s History Project, founded in 1980, is a nonprofit educational organization committed to recognizing and celebrating women’s diverse and significant historical accomplishments. Each March, the group highlights the accomplishments of women in all professions. This year’s theme is “Honoring Trailblazing Women in Labor and Business.”

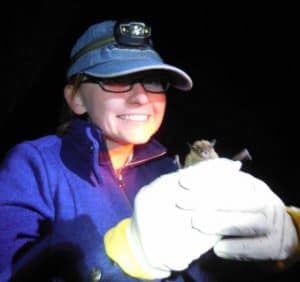

Lindsey Troutman on a mist netting survey to identify presence of bats on Fort Huachura, Arizona. ©Betty Phillips

In cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, TWS is pleased to highlight the contributions of women in wildlife conservation and management in the agency’s Women in Science series.

USFWS biologist Lindsey Troutman can best be described as enthusiastic. Although she is new to the Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office (SFWO), her passion for wildlife and conservation dates back to her childhood growing up in Phoenix, Arizona. During her short tenure at SFWO, she has already worked with a team to provide consultation to landowners and the state of California. Her work also requires engaging with a variety of external partners, like Pacific Gas & Electric Company and the Army Corps of Engineers. Lindsey’s responses to the five questions below are a true demonstration of her passion for conservation and commitment to excellence in science.

- Why did you become a biologist?

My home growing up was continuously full of pets, from hamsters to Rottweilers, and my dad taught me that they always ate first before we did. I also had the chance to go camping with my family as a child, and it was wonderful to get to just be outside in something so different than the city. I think this must have stemmed my urge to do something involving wildlife and nature, especially something to do with their wellbeing. When I finished high school I really didn’t know what exactly I wanted to do, but knew that I needed a degree in some sort of animal-focused program. I was not very great with blood, so I decided to stay away from the veterinarian aspect of things. From research I did on schools, it looked like the University of Arizona had a great wildlife conservation program, so I decided to go for it. I fell in love with the drive that my professors and peers had of caring for wildlife. I already had an innate need to protect creatures, and conservation was the perfect way to discuss this in large scale. I then started searching for internships and jobs that focused on some form of conservation. During one of my internships as a natural resources specialist, I realized that focusing my efforts as a wildlife biologist to conserve and care for species of concern would help fulfill my passion for caring about wildlife, while also assisting in a large movement toward preserving threatened and endangered species.

- What aspect of wildlife biology are you most passionate about?

I want to do what is best for the animals. I’ve read and experienced a lot of how humans negatively changed the ecosystems that wildlife thrives on. We don’t always consider the effects that can occur from our actions, and I just want to try my hardest to consider them, and make them be non-harmful to the animals. Each species is important to our world, why wouldn’t we want to make things better for all of them — including humans — if we can?

- What do you find most challenging about your work?

I find the most challenging part revolves around trying to do your best, but knowing that there is so much we don’t know. Research continues even when the data indicate we’re doing the right thing. Sometimes conservation efforts produce unanticipated results. One example of this is the black-footed ferret. In the initial effort to create a captive breeding program, some ferrets died due to a disease contracted before they were in captivity, which quickly spread to the others. Learning from this, scientists captured the remaining population, which served as the foundation for a successful program for a species that now has a number of reintroduction sites, as well as breeding facilities with hundreds of thriving ferrets. The environment is dynamic, which makes ongoing research essential to ensuring that we account for as many variables as we can in our efforts to preserve plant and wildlife species. The challenge lies in looking at many aspects of each situation and trying to choose the best solution, supported by science, to produce the best outcome.

- What three tips would you give someone in becoming a wildlife biologist?

Try everything. Whether it’s learning to drive a tractor, joining co-workers for happy hour to get to know them, helping out with seining for salamanders, or taking a job across the country because you think it sounds cool, try it. Connections and skills are what you need to evolve in a biology career. Also, it’s just really fun; you never know what activities you may fall in love with.

Ask any question. I don’t just mean about how to do specific jobs or completing forms. Ask about how your boss got to the position he or she are in if you aspire to be like him or her one day. Ask what the most exciting part of someone’s career has been. Ask about mistakes people have made and what they wish they would have focused on more in their career. Ask about anything you are interested in. Usually biologists are willing to share, especially the entertaining stories.

Spend some time researching the different opportunities that are out there as a wildlife biologist. The title “wildlife biologist” encompasses a wide range of job activities. If you feel more comfortable being out in the field surveying, build your resume with activities and skills that show you aren’t afraid to get dirty. If you enjoy the security of a consistent schedule but still want to benefit species of concern, working as a Section 7 biologist, writing consultation about proposed projects, could be a great opportunity for you.

- What are you most hopeful about as it relates to conservation?

I am hopeful in seeing how many people are now viewing the environment and wildlife as a resource and place to love, not just as something to be owned. There has been such a big push recently for environmental conservation, and I think that it will keep momentum. So much new technology has come about to make life both efficient and environmentally sound. It also is wonderful to see families going out and exploring nature, while recognizing that they should be aware of their footprint. When a kid gets to play in the mud and see how beautiful the outside world can be, there is hope that he or she will also want to conserve it for their children too.

Header Image: Lindsey Troutman is a wildlife biologist for the Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office. ©Veronica Davison, USFWS