Share this article

TWS celebrates 80 years of science and conservation

As conservationist Aldo Leopold was first sitting down to write what would become his iconic A Sand County Almanac, he and a group of dedicated wildlife managers and biologists were at work creating something else they hoped would stand the test of time.

On Feb. 28, 1937, practitioners of the fledgling science of wildlife biology gathered at the North American Wildlife Conference in St. Louis and formed an organization dedicated to advancing their profession. They called it The Wildlife Society.

Eighty years later, the Society remains as committed to the ideals of science and conservation as it was when it was founded.

“The whole idea from the very beginning was that science had to play a key role in conservation and conservation had to play a key role in science,” said TWS Executive Director Ken Williams. “That whole idea of those two wings was embedded in Leopold’s view from the very beginning.”

At the time of its founding, wildlife conservation was evolving from a focus on game breeding to something broader and rooted in habitat. This cadre of wildlife biologists found themselves facing a skeptical public.

“The field as we know it,” wrote biologist Paul Errington, one of the founders of TWS, in a 1940 editorial in The Journal of Wildlife Management, “is only of recent development in this country and is an offshoot of ecology and conservation — which are themselves comparative newcomers not wholly accepted by the public as integral to existence.”

Errington warned members not to get discouraged.

“How much wildlife management may be judged essential to human welfare or only another luxury is, of course, something that we may be due to find out,” he wrote.

While that battle still continues, in the decades after he wrote those words, wildlife biologists would find themselves increasingly tied to human welfare as environmental awareness in the country grew. Federal laws like the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA), as well as a host of statutes passed at the state level, required impacts on wildlife and habitat to be taken into account on a range of activities on public and private lands, from oil and gas drilling to logging.

“That didn’t exist in the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s and ’60s,” said TWS President Bruce Thompson, “but in the last 50 years [NEPA] has caused society to give regard to its natural resources.”

As a result, wildlife management has expanded, Thompson said. Wildlifers have had to become more aware of the evolving regulatory landscape as well as the natural one, and the field has expanded to include wildlife consultants, a profession Leopold and others hardly could have imagined.

“Mostly what’s stayed the same is the passion, dedication and professionalism that wildlifers continue to inherently have,” Thompson said. “Wildlifers traditionally arose from primarily a farm background. They were close to nature. They hunted. They recreated in the outdoors. They had a direct, close connection to wildlife. That has changed dramatically over the years, but I don’t think the passion and dedication has changed. “

The Wildlife Society has also increased its focus on policy over the years, expanding its governmental affairs program and building partnerships with groups like Ducks Unlimited to press for science-based natural resources policies at the national level.

“We are reconnecting with the great vision for wildlife conservation and science that was expressed by Leopold 80 years ago,” Williams said, “and it’s the wave of the future.”

Leopold and the other founders —like mammologist Olaus Murie and ornithologist Waldo McAtee — couldn’t have imagined the expanding role that wildlife management would come to play on the American landscape and around the world. But as he spoke as president at TWS’s annual meeting in 1940, Leopold seemed to sense the future that science and conservation would play together.

“We may, without knowing it,” he said, “be helping to write a new definition of what science is for.”

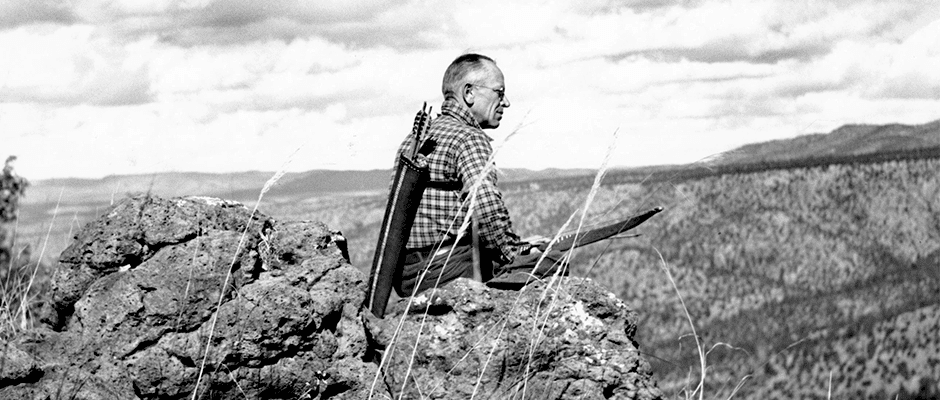

Header Image: Aldo Leopold, a founder of The Wildlife Society, looks out over the Rio Gavilan region of the northern Sierra Madrid the 1930s. ©US Forest Service