Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Eastern box turtle

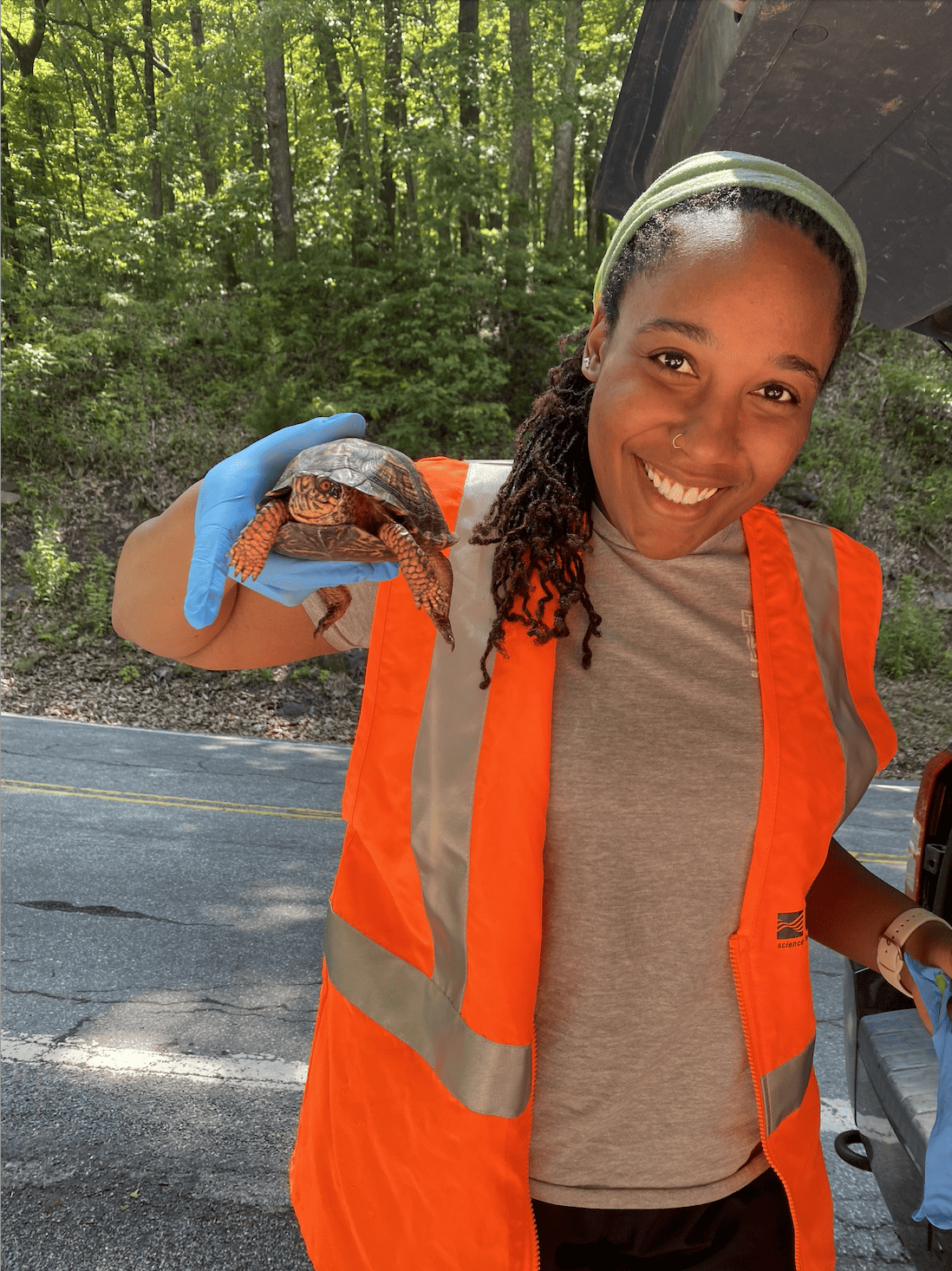

TWS 2023: Helping return eastern box turtles to the wild

Disease can complicate relocating turtles seized from the wildlife trade

When authorities seize eastern box turtles in crackdowns on wildlife tracking, they don’t always know what to do with them.

Releasing them back into the wild can be difficult. It often isn’t clear where they came from or what diseases they may carry with them. As a result, they frequently end up in captivity for educational purposes or euthanized.

Zoie McMillian, a PhD student in the wildlife conservation department at Virginia Tech, is setting out to tackle the disease part of this question to help inform future eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) releases. She presented her preliminary findings regarding best ways to test them for diseases in a poster at The Wildlife Society’s 2023 Annual Conference in Louisville, Kentucky.

Originally from Richmond, Virginia, McMillian had some firsthand experience with eastern box turtles growing up. “I found one with my best friend as a child,” she said. “We found it in the woods outside of our house and put it in a shoebox. We brought it back to our parents to keep it, and they said no. That was a good thing. While I know that now, most people don’t know, and I have some empathy and understanding for people who might be interested in turtles but don’t know the best way to show it.”

Eastern box turtles are a forest-dwelling species that’s declining in the eastern U.S., due in part to habitat loss and fragmentation from urbanization and roads. “It’s kind of getting attacked from multiple angles,” McMillian said. It’s also facing declines due to collections for the pet trade. “Eastern box turtles are one of the most highly traded turtle species worldwide,” she said.

McMillian set out to find eastern box turtles in the mountains of Virginia by conducting roadside surveys. When she finds them she takes measurements, determines their size and age, and makes note of any obvious illness or disease. She also swabs them to test for salmonella, herpesviruses, mycoplasma, ranavirus and iridoviruses.

In her poster, she shared the best way to find the turtles, which are quite elusive. “If it’s not rainy and warm during the months that they’re out, like the summer and spring when they’re basking and looking for mates and nesting opportunities, then they’re really hard to find,” she said.

Looking in rural areas and developed areas, McMillian measured temperature, cloud cover, if it rained recently, time of day, how fast she was driving and if the roads were gravel or concrete.

She found 22 turtles and determined that the main predictor for detecting the turtles ended up being driving speed. She thinks that may have something to do with the fact that she drove slower on gravel roads, where there ended up being more turtles.

The next step is looking at the disease profiles of some of these individuals. That’s important because if they want to release seized turtles back into the wild, they need to have similar disease profiles so as to not spread diseases.

McMillian said while biologists have had some success with releasing other species, like gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus), from captivity, there are challenges with eastern box turtles. Oftentimes, when you move a turtle from where it’s comfortable, it can run into trouble finding food, for example.

“Having the disease samples will help, but I think there are lots of moving parts,” she said. “There are lots of different parts of this process that could be improved to really help with preventing the decline of these wild turtle populations like enforcing the laws as well.”

Header Image: McMillian holds an eastern box turtle she collected on a road survey. Credit: Courtesy Zoie McMillian