Share this article

Two reptiles sharing shade or hired help guarding the gate?

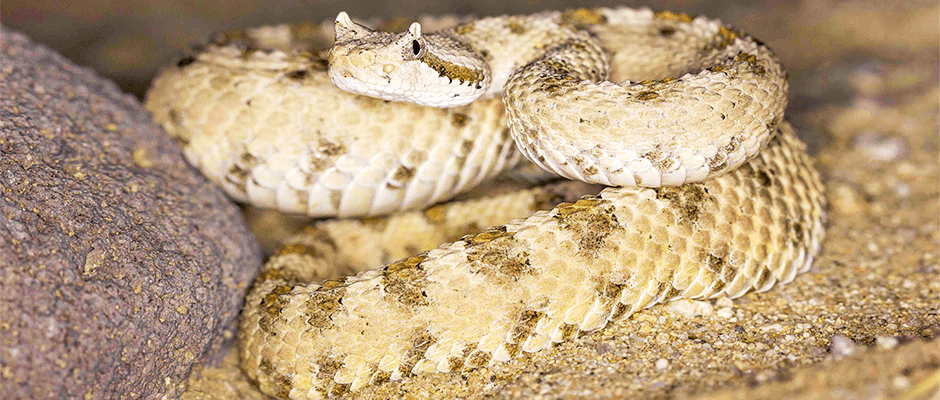

It’s the small details and the slow progression of change, punctuated with extremes, that is most interesting for biologists and nature enthusiasts in California’s deserts—especially those that you find just below the surface. This was true one clear hot day in mid-July when biologists from the Natural Resources Group, Inc., who were at the new West Mojave Conservation Bank checking camera traps for Mohave ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus mohavensis), peered into a burrow and saw the menacing horns (supraoculars) of the Mojave Desert sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes cerastes) [Side note: it is these supraoculars that give the Mojave Desert sidewinder its nickname, the “horned rattlesnake”]. The sidewinder, while venomous, is not particularly aggressive so getting a closer look was definitely in order. Using cell phones to reflect sunlight into the burrow revealed that this attractive adult snake was not alone, but rather was nestled up against an adult desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), both seemingly enjoying a respite from the heat.

Mojave Desert sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes cerastes) with an adult desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii). Photo courtesy of Ryan Lopez and Skip Moss, Natural Resources Group

Tortoise burrows are used by many forms of wildlife, some of which depend on tortoise burrows for shelter and survival (burrow commensals). Consequently, finding another animal, such as a sidewinder, within a tortoise burrow is not uncommon. It is seemingly uncommon behavior for a tortoise and burrow commensal to be using the burrow at the same time and in such close proximity. This behavior may not be surprising though, as these species pose no direct threat to each other and do not compete for resources. In fact, for a tortoise, having a venomous snake between itself and the exit of a burrow might have a mutualistic behavioral advantage in the form of a predator repellent, increasing its chance for survival. For the sidewinder, having tortoises around creating burrows is essential, so protecting the opening of a burrow is a welcome tradeoff.

The biologists at Natural Resources Group, Inc., used an iPhone 6 and the app GIS Kit (hat tip to Jeff Davis) to capture the photo and record geographic data. This chance encounter was documented at an elevation of 1,992 feet above sea level, within creosote bush scrub habitat co-dominated by Ambrosia dumosa and Larrea tridentata. Ground surface temperature in the shade was 125° F, and the temperature of the tortoise’s shell in the burrow registered as 105° F. Temperature was measured using the Etekcity Lasergrip 1022 non-contact Digital Laser Infared Thermometer. The proposed West Mojave Conservation Bank is located approximately 12 miles north of California City in eastern Kern County, CA.

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 newsletter for the San Joaquin Valley Chapter of TWS. The newsletter can be viewed here.

Header Image: Mojave Desert sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes cerastes) ©Rahul Alvares