Share this article

To save Hawaiian honeycreepers, conservationists make allies with mosquitoes

Biologists are using modified mosquitoes to reduce deadly avian malaria

Biologists in Hawaii are fighting one pest with another in an effort to save endangered honeycreepers from extinction. The native birds are disappearing due to the spread of avian malaria by mosquitoes, which were accidentally introduced to the islands in the 1800s. As the climate changes, mosquitoes are able to survive in higher elevations. That has put more honeycreepers at risk in areas that used to be mosquito-free refuges.

To combat these invasive mosquitoes, conservationists are bringing in millions of other mosquitoes—modified with a bacteria that prevents them from reproducing. Borrowed from human health initiatives to reduce the spread of malaria, the technique drives down mosquito populations in the wild.

The coalition Birds Not Mosquitoes—made up of organizations including the National Park Service, the state of Hawaii and nonprofits like the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project—is hoping the effort can stave off extinctions. Out of 50 honeycreeper species that once resided in Hawaii, only 17 remain, and some are expected to vanish from the wild this year.

“We are in an ongoing extinction crisis,” Chris Warren, forest bird program coordinator at Haleakalā National Park in Maui, told NPR. “The only thing more tragic than these things going extinct would be them going extinct and we didn’t try to stop it.”

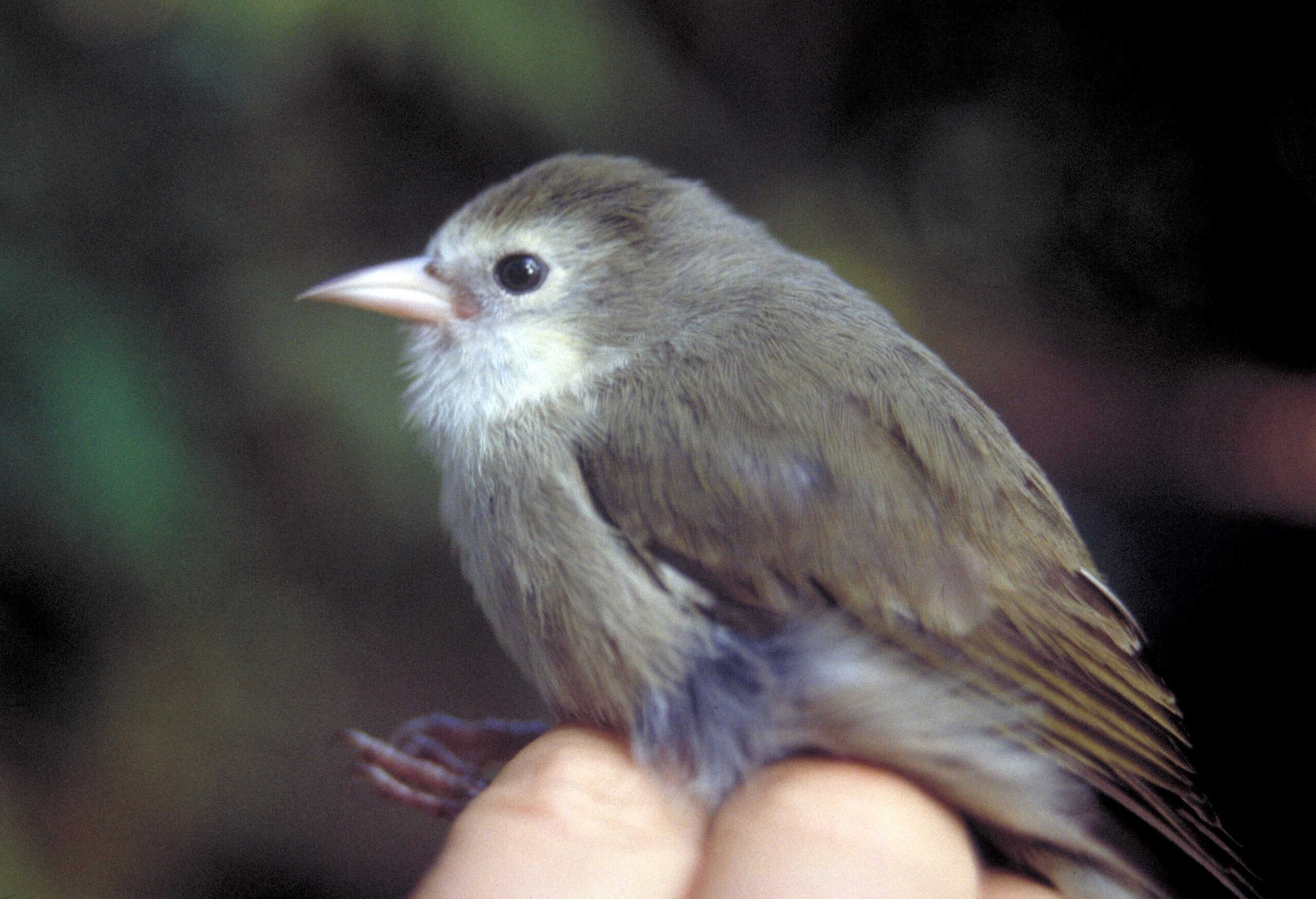

Header Image: Found only on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, the ‘akikiki, or Kauai creeper (Oreomystis bairdi), is expected to become extinct in the wild this year. Image Credit: Carter Atkinson/USGS