Share this article

Temperature affects more than just survival

As the climate changes, researchers often focus on how temperature may affect a species’ ability to survive. But survival isn’t the only concern. Changing temperatures could affect species’ ability to reproduce, and that could lead to changes in the traits that animals use to attract mates and intimidate reproductive rivals.

Understanding those effects, researchers say, will give us a better idea of which species may do well as the climate changes and which ones may have a harder time.

“We’ve over the years learned a lot about how organisms adapt to survive and grow at the temperatures that they experience, but we’re only really now coming to realize how organisms alter their reproductive behaviors and reproductive traits as adaptations to their climates,” said Noah Leith, a PhD student at St. Louis University.

To paint a more holistic picture of how species would fare under climate change, Leith led a study published in Ecology Letters looking at different ways temperature can affect species’ reproduction and what role that may play in their ability to persist. “Reproduction is probably more closely linked to climate adaptation than we realized and that we’ve appreciated before,” he said.

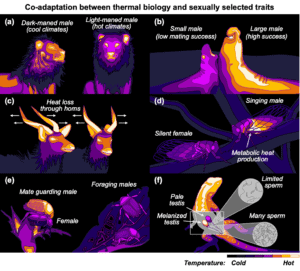

This graphic shows examples of how interactions between temperature and sexual selection drive the co-adaptation of thermal physiology, thermoregulation and sexually selected traits in animals. Credit: Noah Leith and Ecology Letters

Leith and his team searched the literature for species with sexual traits that alter their body temperatures. Examples weren’t hard to come by, he said, even though few studies directly investigated these interactions. Most of the research focused on survival, but they found a ton of overlooked indirect examples where reproductive traits seemed to affect how specie have adapted to their climates. They synthesized those examples, and a few stood out. Male lions that have dark manes to attract females, for instance, also absorbed more heat from the sun, making them more prone to heat stress.

In other cases, sexual traits proved beneficial for thermal regulation. Longer horns help male antelopes fight over access to mates, but they also dissipate the tropical heat. When cicadas sing to attract mates, their body temperatures rise by about 20 degrees.

It seems like that would cook them from the inside, but it really helps them stay active at times of day when their rivals might not be as active or there might not be as many predators around,” Leith said. “They’re better at competing for mating success because they can heat up their bodies that much.”

Understanding these dynamics could help us understand how wildlife may adapt—or not adapt—as temperatures rise, Leith said.

“So much of the way that we try to understand how organisms are going to respond to climate change is by just looking at whether or not they’re going to survive at a given temperature,” said Michael Moore, a co-author of the study and assistant professor at the University of Colorado Denver. He conducted the research as a postdoctoral fellow at Washington University in St. Louis. “That’s really fruitful, and that’s a really nice first pass at understanding these processes. And we’ve made a lot of progress doing that. But what I think this paper really illustrates is that we need to take a more holistic approach at looking at the whole organism and everything an organism needs to do in order to pass on its genes to the next generation to understand how organisms are going to respond to rising temperatures.”

Header Image: Lions with darker manes attract more mates, but they also attract more heat. Credit: Mario Micklisch