Share this article

Study takes ‘vital signs’ of Yellowstone ecosystem

If you want to know how healthy an ecosystem is, wouldn’t it help to have a list a vital signs — the sort of summary a doctor uses to check on patients’ health?

That was the idea behind a Montana State University study, which looked at a variety of measures of the health of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to paint a picture of how well it is faring.

Increased population and density and a changing climate are impacting its ecological health, researchers found, raising concerns about the decreasing snowpack, water systems, and forest intactness and climate suitability.

“These forces are projected to increase in the coming decades, raising questions about the future for sustaining the [Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem] as a wildland ecosystem,” researchers concluded.

“The goal of the paper was to help people who are interested in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to grasp what we know about how well it’s being sustained ecologically, get the approach in the literature, and provide an example that groups in other areas can work from.” said Andrew Hansen, director of Montana State’s Landscape Biodiversity Lab, who co-author the paper in Ecosphere with Linda Phillips, a research scientist in MSU’s ecology department.

The wildland health index shows increased population and density, as well as a changing climate, are affecting the overall ecological health of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. ©Linda Phillips

The project was funded in part by the NASA Applied Sciences Program, which seeks ways to help decision-makers apply science. Hansen said he saw a chart of vital signs as a way to evaluate important elements of ecosystem health, point to whether their improving of worsening and communicate it to diverse groups, including both the public and the scientific community.

“As a group of scientists and managers, we’ve become quite good at highly-focused studies and conservation strategies, but we almost always do it in isolation and don’t really have a sense of what’s going on in the entire system,” he said. “Maybe an outcome of that is, something falls through the cracks.”

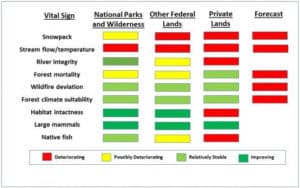

The paper’s wildland health index listed 35 vital signs for the Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, surrounding federal lands and private lands and boiled them down to nine categories of particular interest to policymakers.

Researchers found that while wildlife — particularly large mammals like gray wolves (Canis lupus) and grizzlies (Ursus arctos) — were doing well, native fisheries were suffering. Conditions inside the parks were good, but the health of private lands was poorer. The forecast raised alarms about projected future land use and climate-related changes.

“These examples, I think, demonstrate how to decide what management to do today,” Hansen said. “You need to know what’s happening across the decades, but you also need to know what are the potential future directions, so we know what decisions we should be making today.”

Header Image: A grizzly bear appears with a cub in Yellowstone National Park. ©Frank van Manen/USGS