Share this article

Study maps ‘climate corridors’ for shifting species

As climate change impacts ecosystems around the world, wildlife managers are expecting to see many species leave their current ranges for new areas better suited to them. But where are those new refuges? How will the animals get there? And what can managers do to help give them safe passage?

To try to answer those questions, researchers used computing methods to map North American “climate corridors” leading from current climate types to where those climates will occur in the future. It’s the first time scientists have ever mapped climate connectivity over an entire continent, said Carlos Carroll, a researcher at the Klamath Center for Conservation Research and lead author on the study published in Global Change Biology.

“Many organisms will not be able to persist in refugia if climate changes past a certain threshold,” Carroll said. “They’re going to have to shift.”

Researchers found they’ll generally follow routes along passes and valley systems that trend in a north-south direction, and they’ll seek the drier, leeward slopes of mountain ranges. These paths don’t necessarily follow a straight line, Carroll found. Because species often seek out specific conditions, some are likely to follow a circuitous route to find them.

“If you were adapted to alpine areas and a straight line was across a valley, you would not take that route,” Carroll said. “You would go a more roundabout way using more montane habitat.”

Carroll and his team, which included biologists from Montana, Canada and the U.S. Forest Service, found several existing parks and protected areas with high importance for climate connectivity in western Canada, Arctic Canada and Alaska, the Southwest and southern Mexico. Many areas that were likely to be key spots for climate connectivity, however, lacked protections and needed more conservation efforts.

The research was part of a broader climate adaptation project Carroll is leading called AdaptWest, a database that maps climate change-related threats to biodiversity across North America. While this research applied a broad-brush approach, Carroll said, the open source tools the team developed allow managers on the ground to adapt them for more detailed studies on smaller areas.

“Many agencies and managers are realizing if they have a mandate to conserve biodiversity and other ecosystem benefits, they need to stop looking at it as a static goal,” Carroll said. “They’re going to have to shift their approaches because of climate change. By developing this, we’re hoping that regional planners will be able to preserve species on the landscape — but maybe not where they are now.”

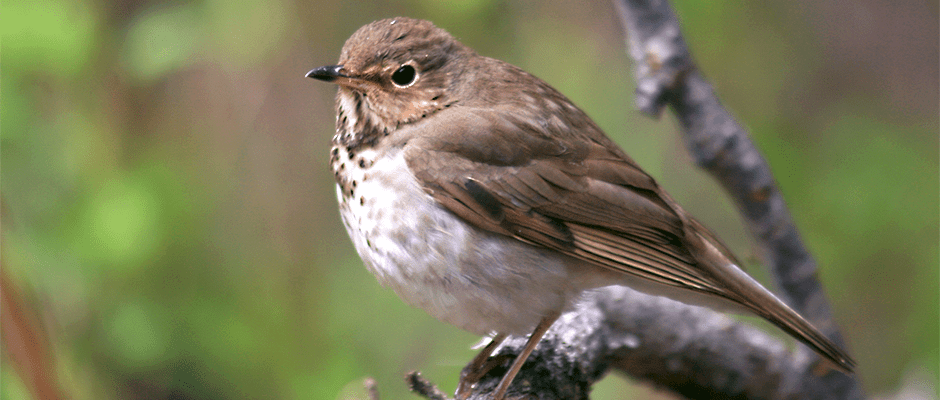

Header Image: As the climate changes, some species, such as the white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis), are expected to shift their current ranges to include new areas that better meet their needs. ©Jeff Ball