Share this article

Space Agencies and Conservation Scientists Collaboration Necessary

If publicly funded space agencies such as NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) collaborated with conservation scientists, they would probably be able to globally monitor biodiversity and help stop wildlife decline — but that’s a big “if” according to an article published last week in the journal Nature.

In a related paper, scientists with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the University of Twente in the Netherlands, urge space agencies and conservation scientists to work together to identify measures to help track biodiversity decline around the world. However, this has proven difficult in the past since there has been a lack of agreement between the two parties on which variables to track and how to translate the information into useful data for conservation.

“With global wildlife populations halved in just 40 years, there is a real urgency to identify variables that both capture key aspects of biodiversity change and can be monitored consistently and globally,” said Nathalie Pettorelli, a researcher at ZSL and a co-author of the article, in a press release. “Satellites can help deliver such information, and in 10 years’ time, global biodiversity monitoring from space could be a reality, but only if ecologists and space agencies agree on a priority list of satellite-based data that is essential for tracking changes in biodiversity.”

Publicly funded space agencies including NASA and ESA are already collecting satellite data and providing the public access to it. For example, NASA’s Sustainable Land Imaging program, which launched last year and provides satellite imaging of the earth, will be collecting publicly available data for the next 25 years. Further, individual tree species or animals can be imaged in great detail by WorldView-3, a private Earth-observation satellite owned by DigitalGlobe, a company that owns and operates satellites based in Longmont, Colo.

Scientists also suggest that vegetation or leaf cover can be measured from space to provide information about biodiversity levels as well as forest degradation. However, there is currently no agreed-upon definition of a forest and no solid decision on what constitutes degradation, making it difficult to use this information.

The next step, according to the scientists, is for ecologists and space agencies to work together to create a list of biodiversity variables that can be monitored by satellite. And they believe that if a biodiversity study is done from space after these variables are defined, there will be a much wider range of information than collecting data on individual species.

“So far biodiversity monitoring has been mostly species-based, and this means that some of the changes happening on a global-scale may be missed,” Pettorelli said. “Being able to look at the planet as a whole could literally provide a new perspective on how we conserve biological diversity.

Lead author of the paper and professor at ITC, University of Twente Andrew Skidmore believes that once scientists and space agencies work together, the space technology available can help conservation efforts.

“Satellite imagery from major space agencies is becoming more freely available, and images are of much higher resolution than 10 years ago,” Skidmore said in a press release. “Our ambition to monitor biodiversity from space is now being matched by actual technical capacity. As conservation and remote sensing communities join forces, biodiversity can be monitored on a global scale.”

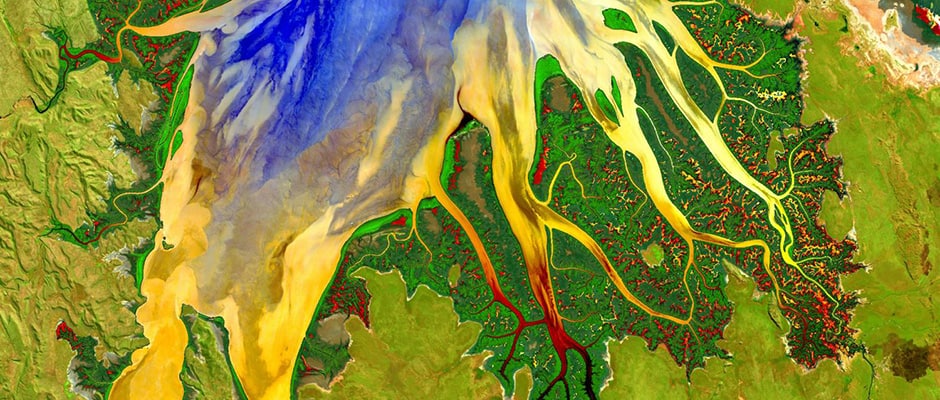

Header Image:

An image of the view over Western Australia on May 12, 2013 was captured by the Lansdat-8 satellite. Scientists suggest that biologists and space agencies work together to develop strategies to globally study biodiversity from space.

Image Credit: NASA US GS Landsat; Geoscience Australia