Share this article

Rock climbers help monitor bats and white-nose syndrome

Robert Schorr, a zoologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program at Colorado State University, was having coffee with a few colleagues, including another bat biologist, when he had an idea.

After discussions about how rock climbers sometimes encounter large numbers of bats, Schorr and his colleagues realized that these climbers might be helpful with bat conservation. White-nose syndrome — a fungal disease that has decimated around 6 million bats in North America — has recently made its way from the East Coast of the United States to the West. The team, including Schorr and his colleagues, was looking at different ways to conduct surveillance on bats in Colorado, where the disease has yet to be confirmed.

Schorr explains that “in the east, there are caves and mines, and when white-nose syndrome hits those, it’s obvious because there are dramatic changes in what biologists see.” In the West, however, bats do not hibernate in large numbers at caves and mines, and may roost in cliffs where they’re more difficult to find, he said.

Schorr and his team received a small grant from Colorado State University’s School of Global Environmental Sustainability to start up an organization where rock climbers can get involved, which they called Climbers for Bat Conservation. The group is the result of collaboration between climbers, bat biologists and land managers as a way to learn more about bat roosting ecology and conservation.

To get the project started, Schorr and his colleagues met with climbers, created a logo, website and social media presence (find them on Facebook), and posted advertisements in climbing gyms about the initiative. They have also had free climbing events where rock climbers can share what bats they’ve seen and can learn more about the project. “The climbers were just as eager — if not more so — than the bat biologists,” he said.

Even though the collaboration just started, some climbers have already started reporting their findings using iNaturalist, a mobile app that allows users to take photos of species that are then identified by experts. “We keep it real simple,” Schorr said, “we don’t want them to touch or handle the bats.” Instead, they simply record their findings as well as the route they were climbing, and when and where they see bats. This way, biologists can go back later to look for bats at these roosts.

Ultimately, Schorr hopes to create a new data-gathering website that can be used by climbers to submit their observations. This way, climbers will know exactly where they should report their findings about bats.

While white-nose syndrome has not yet been reported in Colorado, it has been found as far west as Washington state. As a result, it’s important to monitor the spread of this contagious fungal disease, Schorr said, and using rock climbers as a resource will be extremely helpful to this cause. In fact, the disease was detected in Washington by a hiker who discovered a dead bat with symptoms of the disease.

Schorr and his colleagues hope to access more funds and continue to get the project off the ground through spreading the word about Climbers for Bat Conservation.

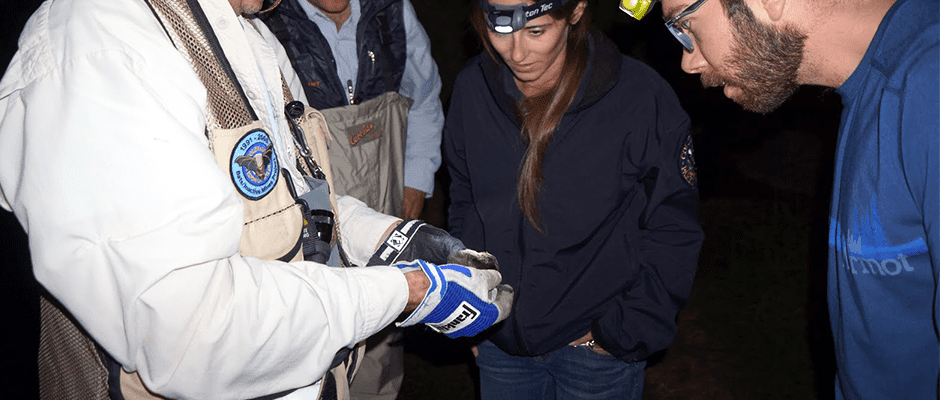

Header Image: Kirk Navo, a wildlife biologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program shows rock climbers the features of a bat. ©Climbers for Bat Conservation