Share this article

Q&A: Heat may provide wildlife with thermal refuge from cats

While invasive species have a massive negative impact on native species and ecosystems around the world, one species stands out both in its overall impact to small wildlife and its pervasiveness. The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service predicted in one study that domestic cats (Felis catus) killed 1.3–4 billion birds and 6.3–22.3 billion mammals annually in the United States alone. Other research has focused on how cats prey upon bats worldwide, and kill up to 466 million reptiles per year in Australia.

Cats also play an important role in transmitting toxoplasmosis to wildlife and humans. The protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii has a complex life cycle, and has been proven to infect everything from raptors to sea otters (Enhydra lutris), to hyenas.

Natalie Briscoe is a research fellow at the University of Melbourne. Courtesy of Natalie Briscoe

But new research published in Conservation Letters shows that some species might be safe from cat predation thanks to their preference for areas too hot for cats. For our latest Q&A, we spoke to the study’s first author, Natalie Briscoe, a research fellow in ecosystem and forest sciences at the University of Melbourne in Australia, to find out more about these thermal refuges.

What are some of the problems cats pose to native wildlife around the world?

Globally, cats are one of the most problematic invasive species, impacting native wildlife via predation, disease transmission and competition. They have had a particularly detrimental effect on birds and mammals, contributing to the extinction of many species of these taxa.

In Australia, small, ground-dwelling mammals have been particularly vulnerable to cat predation. At least 34 mammal species have become extinct since European settlement, and cats have been primary contributors to over two-thirds of these extinctions.

How might thermal refuges protect animals from cat predation?

Feral cats are found across really diverse environments in Australia, including very hot and dry areas. Controlling feral cat populations across this vast area is a huge challenge. Identifying the areas that are natural refuges from feral cats due to climatic conditions is useful, because these may be important places for threatened species.

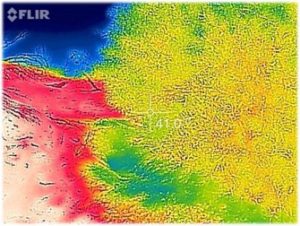

A thermal image showing the coolness, in blue, of a burrow. Courtesy of Natalie Briscoe

Our research suggests that large parts of arid Australia get too hot during the day for cats to survive, unless they can shelter in micro-refuges such as rabbit burrows that protect them from the sun and hot temperatures. Using historical weather data from 1990 to 2017, we identified areas that would be unsuitable for cats over multiple consecutive years—up to 27 years in some places—if burrows are not available. These areas may act as natural refuges for prey species from cats. We found that recent observations of the bilby and mulgara—native mammals known to be vulnerable to cat predation—were associated with these areas, suggesting that thermal refuges can provide some protection from cat predation.

Are there other potential refuges for prey species from cats besides thermal refuges?

Other environmental factors may also help to protect prey species from cats. For example, cats are better at hunting in some types of habitats than in others, and so species able to exploit these less preferred areas may gain some protection from predation. It has also been suggested that the presence of dingoes (Canis familiaris) may create cat-free refuges in space or time by influencing the abundance, habitat use or temporal activity patterns of feral cats, although evidence for this is mixed. In Australia, cat-free refuges like fenced-off reserves or cat-free islands, where cats have been eradicated or never introduced, play an important role in the conservation of species very vulnerable to cat predation.

Feral cats have driven roughly two dozen mammal extinctions in Australia, where there are no native feline species, since introduction. Credit: Hugh McGregor

How do these findings affect wildlife management and conservation?

Our findings may help others detect populations of species threatened by cats but able to tolerate thermally harsh conditions, such as the night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). A key challenge for conserving this species is simply locating populations across remote areas of inland Australia.

Our analyses also show where removal of potential cat refuges can be most effective in limiting cat populations. Cats don’t dig their own burrows, so they rely on burrows made by other animals. In areas where cats are dependent on burrows, removing rabbit and fox burrows could be an effective management strategy to reduce feral cat densities, although consideration should also be given to native wildlife that may rely on these resources. At one of our field sites, we found cats used piles of woody debris created in association with road management. Our research highlights that limiting access to micro-refuges like these can be really important.

The Wildlife Society’s position statement on feral and free-ranging domestic cats.

Header Image: Feral cats are a problem for native wildlife around the world. Credit: Hugh McGregor