Share this article

Putting a number to bee habitat

When Rick Johnstone went about improving bee habitat in a utility easement at Maryland’s Patuxent Wildlife Refuge, he could see the difference taking place on the ground within a year. Invasive plants like autumn olive and lespedeza were vanishing. Native grasses and forbs were taking their place. The right-of-way was turning into the sort of successional prairie landscape where pollinators thrive.

It’s not too hard to see these changes like these. But can you measure them?

“We wanted to have some means to be able to say, ‘This is providing good habitat,’” said Johnstone, president of Integrated Vegetation Management Partners (IVM Partners, Inc.), a Delaware-based nonprofit that serves as a liaison between utilities and public agencies to improve wildlife habitat in rights-of-way through vegetation management and conservation practices.

His IVM Partners botanist, Michael R. Haggie, and statistician, Hubert A. Allen, Jr., came up with a habitat scorecard — a pollinator site value index to rate how well these managed landscapes serve as habitat for honey bees (Apis mellifera), bumble bees (Bombus spp.) and other wild bees.

The five-category index rates landscapes up to a score of 1,200. Most of that — up to 500 points each — is based on how well they provide nectar and pollen. But the index also rates how long plants flower on the land (100 points), the diversity of beneficial plants (50 points) and the availability of bare ground, snags and pithy stems that serve as wintering habitat for bees (50 points).

“It’s kind of like a snapshot of what’s there now and what benefits it provides,” Johnstone said.

Since 2015, Bayer Crop Science has supported their work through partnership and in the form of Feed a Bee forage grants for establishing additional pollinator habitat and conducting outreach and education efforts.

Often, utility companies simply mow their rights of way, he said, which makes them easy to care for but doesn’t create much habitat.

“Whatever you cut down comes back,” Johnstone said. “When you have nonnative, invasive plants, they take over. Then, your habitats are very much degraded for pollinators, birds or other types of wildlife.”

Strategically using herbicides can remove the invasives in a way that allows the native plants to return, he said, creating the mix of plants the bees rely on. “We’re not introducing species,” Johnstone said. “We’re managing species that have always been there in the seed bank with which native insects have co-evolved and are used to feeding on.”

He developed case studies for right-of-way improvements around the country, including the USFWS’s Patuxent National Wildlife Refuge, where treatment converted a mowed strip of trees and invasive plants into a corridor of native grasses and shrubs. Its pollinator site value index score went from 25 in 2011 to 117 for honey bees and to 177 for bumble bees four years later.

“You end up with a fairly stable plant community that takes less and less inputs as you go along,” he said.

At another Maryland site, Johnstone said, federal agency partner biologists counted 147 bee species, 120 bird species and 40 species of butterflies after the restoration efforts.

IVM Partners would like to develop a similar index for butterflies and moths — particularly as the monarch butterfly comes under consideration for being listed as an endangered species.

“It’s kind of timely to have this done now,” he said. “We need the answers.”

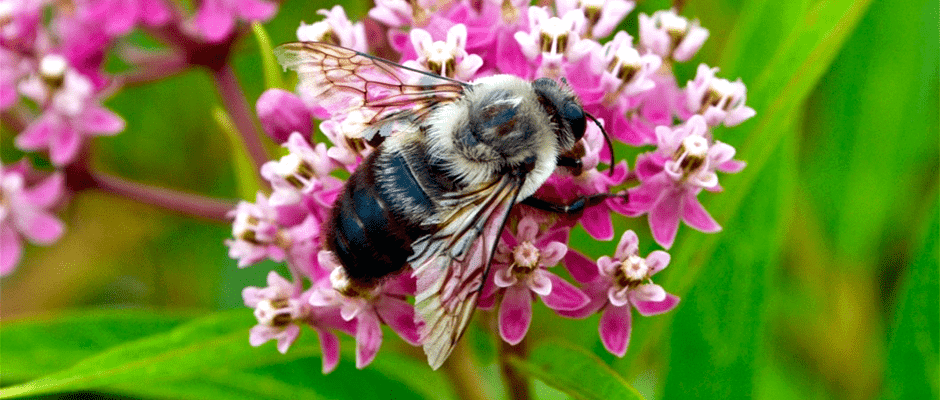

Header Image: The return of native plants creates important habitat for bumble bees and other pollinators. ©IVM Partners, Inc.