Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Cougar

Pacific Northwest cougars can island hop

The discovery offers a new understanding of how cougar populations may be connected

Cougar M161 had a great stretch of territory in the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state. Wedged just below the Canadian border between Puget Sound, the Salish Sea and the open Pacific Ocean, the lush forests supported about 40 cougars across 3,600 square miles.

But the peninsula just wasn’t enough for M161. “This young male decided to try swimming,” said Mark Elbroch, the puma program director for Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization.

On July 14, 2020, the cougar left the mainland, setting out on a brisk 1-kilometer swim from the eastern end of the Olympic Peninsula to Squaxin Island, just southwest of Seattle in Puget Sound. The journey offered a new range for M161 and a new way of understanding connectivity between cougar populations in the region.

“It was an amazing possibility because we could see all kinds of things open up,” Elbroch said.

He and his colleagues had collared M161 several months earlier as part of a larger project tracking the activity of cougars (Puma concolor) in the peninsula. Among other things, the researchers were interested in the connectivity of the landscape for the big cats in this part of Washington state.

The cougar population in the peninsula has the lowest genetic diversity in the state and the highest level of inbreeding, Elbroch said.

The area is relatively large, including protected areas like Olympic National Park and the Olympic National Forest. But Puget Sound and Seattle on other side of the water were thought to be natural obstacles to the movement of cougars from the peninsula to other wild areas, such as Mount Rainier National Park.

The researchers tracking M161 and other cougars were surprised to find that water may not pose such an obstacle.

Elbroch suspects the cat may have been scared away from the mainland. “We believe what happened the night he swam is that he was in someone’s yard and the dog chased him,” he said.

The cougar spent a couple of weeks on the island—a reserve of the Squaxin Island Tribe—killing deer and raccoons (Procyon lotor) and making a splash on social media. Its stay was cut short by harvesting, a Tribal report found. Elbroch and his team got permission to examine the remains left on the landscape.

The episode prompted the researchers to reconsider what was possible for cougar connectivity in the area. The fact that M161 swam more than a kilometer to Squaxin means that the cats could access a number of islands in Puget Sound.

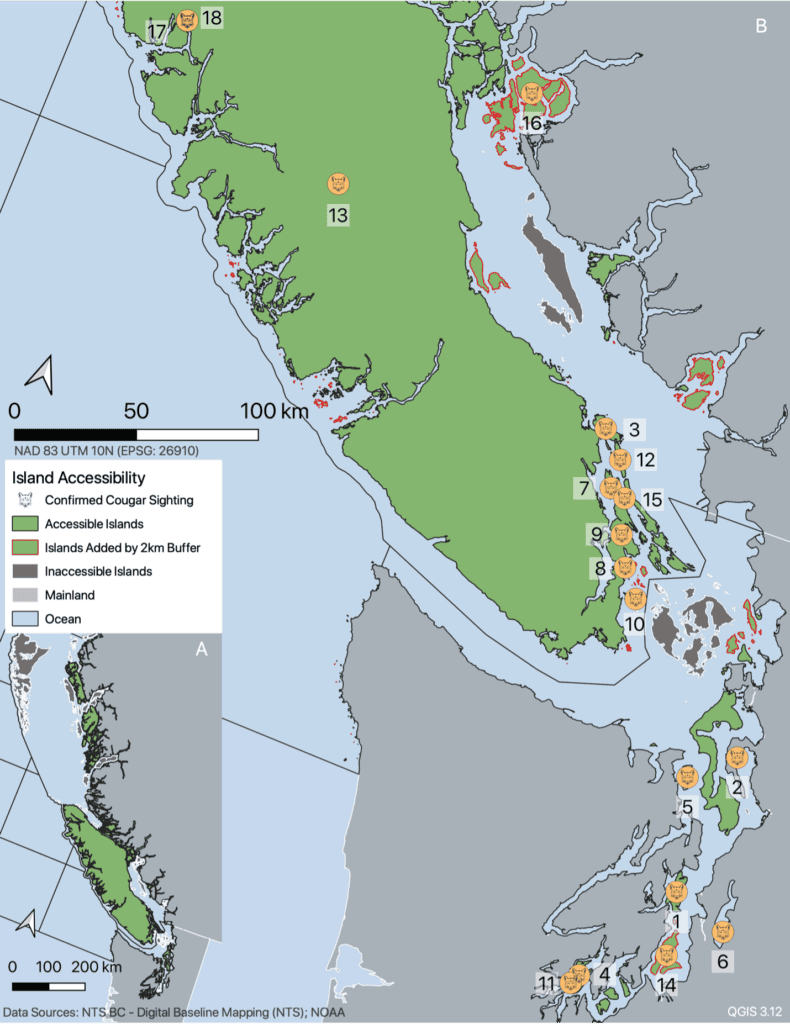

And they have, the team found. The researchers gathered cougar records on other islands in the Salish Sea for a study published recently in Northwestern Naturalist. They confirmed cougar presence at some point on 18 islands, including four that would have required swims of about 2 kilometers. This opens up the possibility that cougars could reach roughly 4,500 islands in the Salish Sea, Elbroch said, and it explains why Vancouver Island in British Columbia has a thriving cougar population.

Squaxin Island, where M161 reached, isn’t that far from the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in the south of Puget Sound. Elbroch said it’s conceivable that the big cats could use several of the islands between the Olympic Peninsula and the Nisqually wildlife refuge to connect to other wild areas further south.

“It’s not just symbolic,” Elbroch said of M161’s feat. “Cats can reach these islands and use them as stepping stones.”

Header Image: A cougar emerges from the water in British Columbia. Credit: Tim Melling