Share this article

New clue sheds light on harmful beak-altering disorder

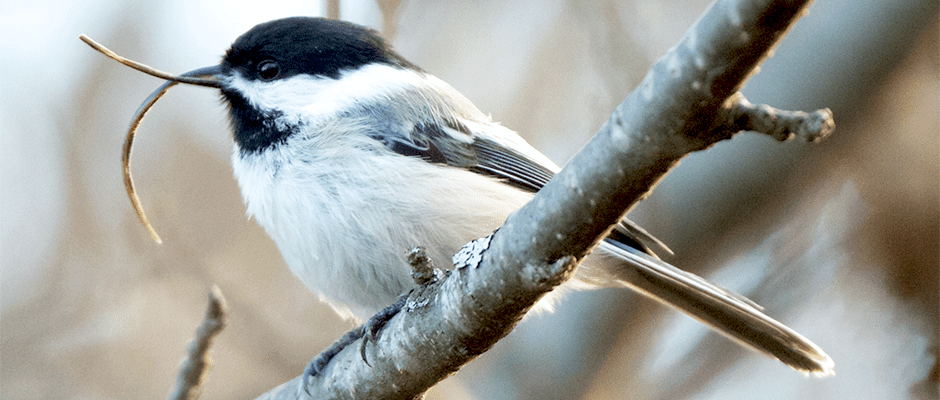

For over a decade, chickadees, nuthatches and other birds in parts of North America and Europe have been spotted with deformed beaks — overgrown to a point where the birds have trouble picking up food and preening their feathers. The cause of these deformities has largely been a mystery — until now.

According to a new study published in the journal mBio, a virus could be to blame for the disease referred to as avian keratin disorder.

Dumbacher handles specimens from the ornithology collection at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, Calif. ©California Academy of Sciences

Coauthor of the study Jack Dumbacher, a curator of birds and mammals at the California Academy of Sciences, first found out about the disorder after reading a paper in The Auk by Colleen Handel and Caroline Van Hemert in which the researchers struggled to determine what was causing the phenomenon in Alaska. “They were hoping to say more about the disease potential and causes,” Dumbacher said, adding that they looked at mites, viruses and bacteria. “They looked at all types of things, but none of them seemed to be related to the disease.”

So, Dumbacher and his team including lead author and postdoctoral researcher Maxine Zylberberg wrote to the authors of the study to send over some samples of the infected birds they were studying. The researchers used a “virochip,” which is a microarray designed to detect viruses. However, they didn’t find any strong hits and decided instead to perform complete genome sequencing on the birds.

“We were sequencing the heck out of all of the DNA from the birds to find anything that looks like a virus,” Dumbacher said. The team found one virus that looked like a Picornavirus, a small group of RNA viruses. Zylberberg assembled the virus and sequenced it. The team named it Poecivirus after the genus of the black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), the species they were able to sequence to genome from and where the disorder was first documented in the late 1990s. But the real challenge for the team was trying to show that the virus was related to the disease, says Dumbacher.

Working with other pathologists, the team also was able to create microscopic images of the affected tissue and dissected beaks and looked for Picornavirus in sick birds. They found that the virus they discovered was present in many of the birds that had the beak deformity and also that the virus was missing in many of the birds that didn’t have the deformity. However, “There were some examples that didn’t test the way we wanted them to,” Dumbacher said. But in these cases Dumbacher says it may be that the virus is no longer present although symptoms persist in the birds, or that the positive tests with no beak deformity could be an early detection of the disease. “We got more and more samples to improve the correlation, that did improve with time,” he said. “It was not 100 percent perfect. We wouldn’t expect it to be. But that makes it harder to move to the next step.”

As part of that effort, Dumbacher and his team are working on achieving the four criteria that are part of Koch’s Postulates — used to show definitively that a pathogen is causing a disease. “But we thought we have enough information to share out to the world so folks can begin looking into it,” he said.

In addition to chickadees and nuthatches, the disease has also been spotted in corvids, crows and jays, and most sightings have been at people’s bird feeders or bird baths. Birds with beak deformities often starve to death; in addition, feathers that haven’t been preened become dirty and matted — and, in the process, lose their ability to keep the birds warm and dry. Further, the virus is found in the birds’ livers and other tissues, but scientists are not sure yet if this might cause liver damage over time.

For Dumbacher, it’s important to continue testing infected birds for Poecivirus. Since the paper has been out, people have already sent him photos of birds with deformed beaks. “The more people know it is an issue, the more people will keep an eye out for it,” he said. Individuals can also report birds with beak deformities on the USGS website.

Dumbacher says it is critical to understand the geographical spread of the disease and how the disease is spreading — whether it’s through water at bird baths, for instance, or by a vector such as a mosquito or tick. People can play a big role in documenting the spread of the disease through taking photos, he says.

“I think we’ve done as much as we can do in identifying the virus,” Dumbacher said. “It’s up to other folks like pathologists in the field to begin really looking for these viruses in birds coming in sick.”

Header Image: A black-capped chickadee with a severely deformed beak sits on a branch in Homer, Alaska. ©Martin Renner