Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Mountain lion

- Grizzly bear

- Wolverine

- Siberian tiger

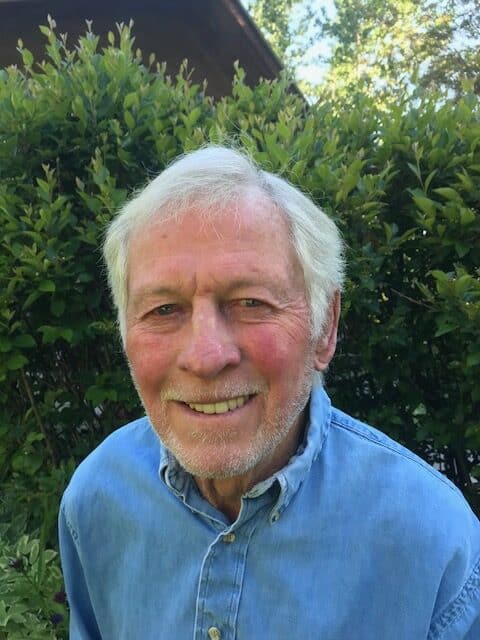

Maurice Hornocker wins Aldo Leopold Memorial Award

TWS member spearheaded the research of mountain lions at a time when carnivores were barely studied

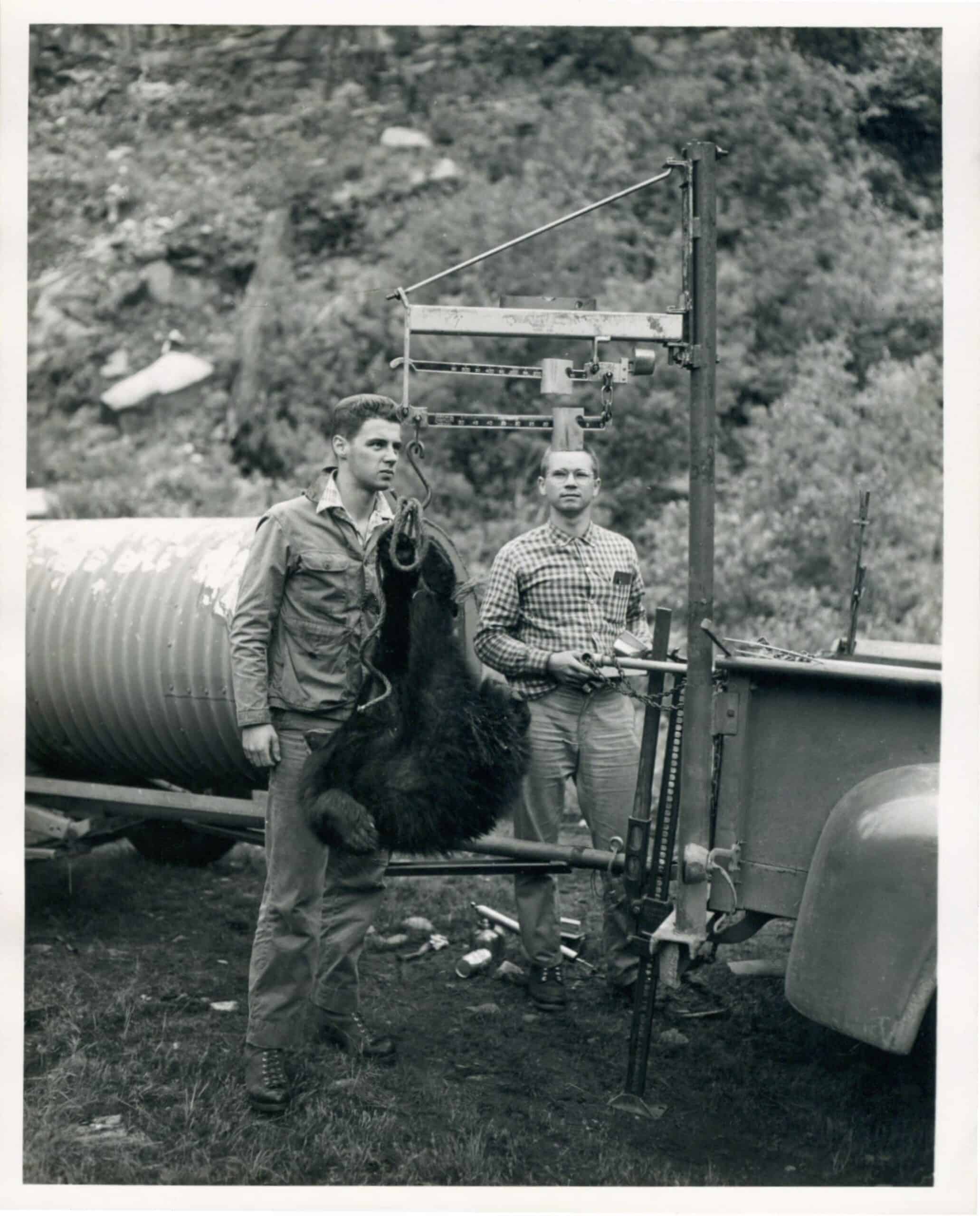

Maurice Hornocker was just beginning his career when he got into what was then a rare subject in wildlife management and research—carnivores. He began working with John Craighead, the 1998 Aldo Leopard Award recipient, in the 1960s, when they started the Yellowstone Grizzly Project. It was a time when nearly all research on wildlife featured game species like birds and large ungulates.

“[Craighead] pointed out that it was not a job but a form of life,” Hornocker said.

After five years working on grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis), Craighead encouraged Hornocker to start researching mountain lions (Puma concolor)—a species that was fairly understudied at the time. His pioneering work on cougars acted as a springboard for more than five decades of field work on a number of species, from wolverines (Gulo gulo) to Siberian tigers (Panthera tigris altaica).

“It’s been an adventure,” said Hornocker, the recipient of the 2024 Aldo Leopold Award, the highest honor bestowed upon wildlife biologists by The Wildlife Society. The award recognizes wildlifers’ lifetime contributions to the field.

Hornocker, 93, grew up on a farm in Iowa, developing a natural curiosity for wildlife in his early years. He received his undergraduate and master’s degrees from the University of Montana, then began his PhD research on mountain lions at the University of British Columbia under another Aldo Leopold Award-winning mentor, the 1970 recipient Ian McTaggart Cowan. For this work, which was the first of its kind, Hornocker studied the ecology of the big cats in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness Area in Idaho—an area relatively free of human effects on wildlife.

With the help of David Johnson, a retired journalist, Hornocker wrote about these experiences in field research on mountain lions in his new memoir, Cougars on the Cliff: One Man’s Pioneering Quest to Understand the Mythical Mountain Lion. This was a time before GPS collars and radiotelemetry technology. “The technology back then was basically a pair of snowshoes and two redbone hounds,” Johnson said.

But technology improved over the years. In the documentary Big Cats in the 1970s, Hornocker is shown tracking a cougar by plane using telemetry in Idaho, for example. His work was featured in a number of different popular articles and documentaries for National Geographic and other outlets.

Hornocker went on to lead the Idaho Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Idaho. In 1985, he founded the Hornocker Wildlife Institute, a nonprofit that was designed to focus on research and eventually merged into the Wildlife Conservation Society, where he worked until retiring in 2005.

“Maurice’s scientific findings and recommendations formed the foundation of a paradigm shift from the view of carnivores as feared ‘vermin’ during an era of bountied killing, toward one of scientifically based management and conservation of carnivore species around the globe,” said Toni Ruth and her colleagues in their nomination letter for the award. “His recommendations for the management of cougars, moving from bounties to the implementation of hunting seasons and quota limits, remain the single most significant change in how cougars are managed in North America today.”

Johnson agrees. “I don’t think anybody has contributed more to the profession as far as mountain lions and big cats are concerned,” he said.

His legacy doesn’t just affect his feline study subjects, but a whole new generation of researchers who he mentored as students over the years. “They call themselves ‘The Disciples,’ believe it or not,” Johnson said.

Hornocker himself prefers to keep the focus off of himself despite winning the award, which he is “humbled and honored” to earn. The message he’d like people to take from his career is that carnivores play an important role in every ecosystem.

“They evolved successfully with their prey species over eons of time, and we really haven’t accepted that in many parts of society,” he said. “That should be considered in any management program.”

Header Image: Maurice Hornocker has worked on carnivore research since the 1950s. Courtesy of Maurice Hornocker