Imagine sitting at home on your couch in an apartment building surrounded by concrete on a noisy city block immersed in a different reality. Your ears hear faint bird calls, and you watch while a golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera) darts by, flying directly into a mist net stretched between two tree trunks. Just as you are about to wrap the identifying band around its leg the microwave oven beeps. You pull off your headset and head to the kitchen to pick up your popcorn.

A new VR experience like this called VRmivora now allows a user to go through the experiences of a biologist tagging birds and processing their genetics. The technology, developed by David Toews, an associate professor at Pennsylvania State University, is available free online at SideQuest.

For our latest Q&A, The Wildlife Society chatted with Toews about this new tool.

Talk me through the development of VRmivora

A pre-med freshman undergraduate student interested in genomics, Lisa Wang, joined my lab. She had a passion for birds and scientific illustration and was interested in 3D models. She mentioned that there’s a campus group, the Center for Immersive Experiences, that develops virtual experiences. She thought it would be cool to work on developing models and gain experience.

I’m a gamer on the side, so I know what’s possible. In modern games like Red Dead Redemption 2, you could spend the whole game observing birds and nature, and it’s so realistic and detailed. I worked it into a proposal for a grant application to the National Science Foundation.

Once we got the funding, we worked with folks in the center, storyboarded what it would look like, wrote a script and then they worked on it. It took a year and a half to make.

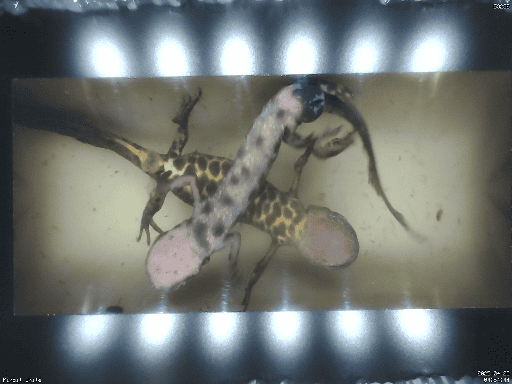

VRmivora is both an outdoor experience and a lab genetics component. We took a GoPro 360 out into the field with us and recorded a morning bird-banding session. One of the most special parts to me is something that isn’t a replica of reality. You can grab the bird in VRmivora and view it from so many angles. In reality, we have very specific ways we hold birds. You can’t look at them from all different angles, whereas in the virtual environment, you can.

What do you want people to take from VRmivora?

This is a cool experience—the technology is interesting and exciting. At the end of the day, the motivation is to make it a bridge, to inspire people to go outside. Part of the reason we developed this is for undergraduate students. We work on migratory birds here only in the spring and summer when students aren’t here.

There are other barriers to participation. It usually requires early-morning weekends with lots of bugs, so convincing people to come out when they don’t necessarily know what they’re getting into is hard. The tool teaches them this is a cool experience—the end goal is to use it to inspire people to go out.

What are the next steps?

This program will run in schools as part of DNA Day, when graduate students go into classrooms to talk about DNA science. VRmivora will teach high school students about science and show them that the people who do science are real people. They’re not just like cartoon lab coats.

What would you do differently if you could do it all again?

The 360 video is cool, but it’s hard when you’re working in 360 degrees to direct anyone’s attention to something like a bird going into the net. A director can point to you towards the action as an audience member by changing the camera angle. You can’t do that when you’re filming in 360 degrees, so version 2.0 would have more directorial flair, allowing you to direct participants’ attention to different action points.

What are the next steps?

One of the things I originally pitched in the proposal was measuring, manipulating and working with the bird in hand. We did it in video format, rather than in a 3D modeling format, because I didn’t think it would be possible to do that in VR. Now the folks at the Center for Immersive Experiences said, “This is something that we could do.”

As an evolutionary biologist who studies birds, this was my own system. But many other interesting wildlife systems could be good for an experience like this. Taking an immersive camera to the Galapagos to study Geospiza finches or stickleback fish in British Columbia, for example.