Share this article

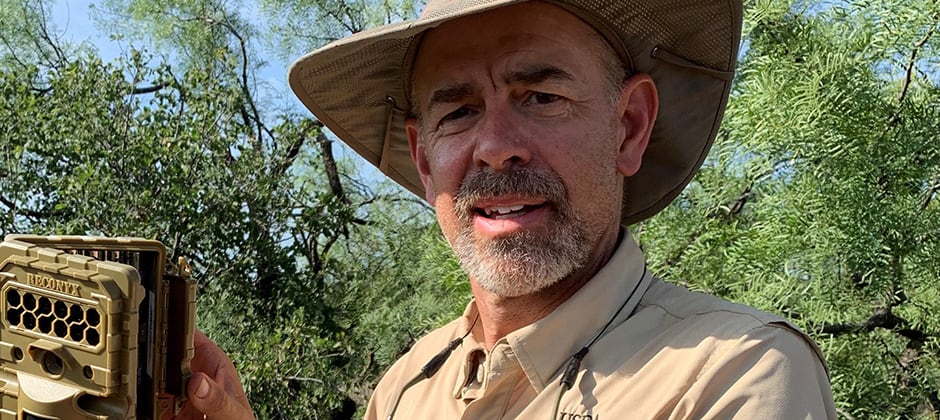

Kurt VerCauteren earns Caesar Kleberg Award

It’s hard to imagine Kurt VerCauteren’s work ever seeming more relevant than now.

As project leader and supervisory research wildlife biologist with USDA Wildlife Service’s National Wildlife Research Center, VerCauteren has been at the forefront of handling wildlife diseases and managing wildlife damage.

With high-profile diseases affecting a range of species—avian flu killing birds, white-nose syndrome wiping out bat populations, chronic wasting disease killing deer and elk, chytrid disease killing amphibians—and a global COVID-19 pandemic that likely began as a zoonotic disease, the importance of dealing with wildlife disease is hard to ignore.

“With COVID and the realization that wildlife played a role in the manifestation of COVID, it brings the whole One Health perspective—wildlife, livestock, humans and the important role that environment plays in that—much more to the forefront,” VerCauteren said.

His decades of work and volumes of research focusing on practical approaches for wildlife managers have earned him The Wildlife Society’s 2022 Caesar Kleberg Award for Excellence in Applied Wildlife Research.

“I was really honored,” VerCauteren said. “I’ve been following this award my whole career. Richard Dolbeer, a retired NWRC scientist and hero of mine was the first recipient when the award was created.”

VerCauteren’s work has spanned from stemming the spread of rabies to controlling wild pig (Sus scrofa) populations. His work on chronic wasting disease upended the common belief that the disease was transmitted only through direct contact between animals, showing that indirect contact and even contaminated soil was a major cause of the spread.

“He has made high-level scientists think about new paradigms and has put new tools in the hands of boots-on-the-ground biologists,” said TWS member Scott Hygnstrom, in his letter nominating VerCauteren for the award.

VerCauteren has published over 230 academic publications, often on cutting-edge strategies, such as using volatile organic chemicals for detecting wildlife diseases. Most of his work has been on nonlethal approaches, including fencing designs to keep destructive wildlife out of farms and ranches, protection dogs to guard livestock from wildlife that may harbor disease and frightening devices to scare off nuisance animals. Recently, as he’s headed up the USDA’s work on feral hogs, his team’s focus has turned to developing a sodium nitrite-based toxicant that can target swine without harming other wildlife.

“The vast majority of my career has been nonlethal work,” he said, “but you have to have innovative lethal tools, too.”

Much of his work has been devoted to addressing deadly wildlife diseases. His work on the spread of bovine tuberculosis to wild deer (Odocoileus virginianus) led to research into chronic wasting disease as it took a growing toll on deer and elk (Cervus canadensis) populations, and then to rabies and raccoons (Procyon lotor).

“I don’t care if it’s a frog or a bear. They’re all fun to work with,” he said. “What you learn from one species applies to the next species.”

VerCauteren’s work has taken him around the world, and his impact can be seen in wildlife fences in Africa and protection dogs on pastures in Europe.

That kind of applied work is what inspires him to take on new projects, and it’s what earned him the Caesar Kleberg award.

“You roll up your sleeves, you make a new tool and you see on the ground where people can be implementing it,” VerCauteren said. “It makes it very rewarding.”

Header Image: As project leader and supervisory research wildlife biologist with USDA Wildlife Service’s National Wildlife Research Center, Kurt VerCauteren, the 2022 recipient of TWS’ Caesar Kleberg Award, has been at the forefront of handling wildlife diseases and managing wildlife damage. Credit: Courtesy Kurt VerCauteren