Share this article

JWM: Winter conditions stress pronghorn the next summer

The Red Desert of south-central Wyoming has long been known for robust pronghorn populations, but in the last two decades, herds have diminished up to 30 percent. The deep snow can be deadly for pronghorn, biologists have found, although the deaths tend to come in the summer, when female pronghorn are likely to die because of the tolls of low body fat from the last winter.

“We found the majority of our adult females dying in the summer, which was surprising because the most challenging time of year for a lot of ungulates is winter, and you’re going to see the greatest die-offs during winter months or in spring shortly after winter,” said Adele Reinking, lead author on the paper published in the Journal of Wildlife Management.

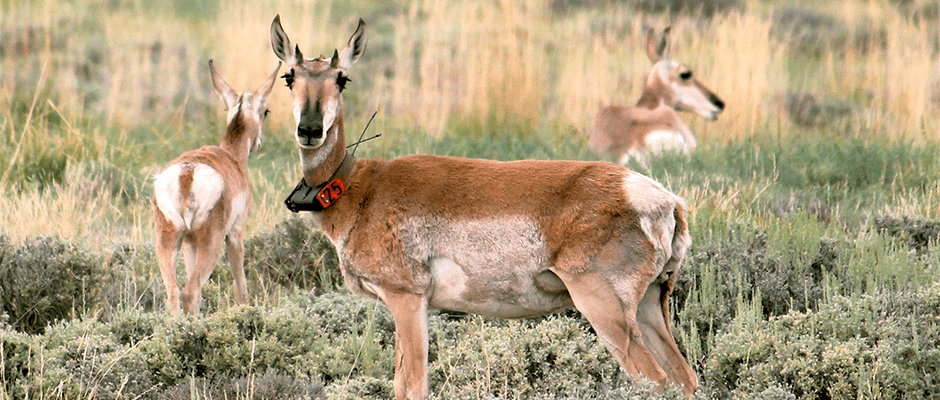

The researchers observed that 80 percent of the female pronghorn they examined died in the summer. To identify the factors contributing to this summer mortality, from 2013 to 2015, Reinking, a graduate research assistant in rangeland ecology and watershed management at the University of Wyoming, monitored 114 adult female pronghorn equipped with global positioning system transmitters.

“If they experienced increased variability in snow depth the previous winter and if they entered that winter in poorer condition, they were more likely to die the following summer,” Reinking said.

It makes sense that slogging through deep snow with their relatively small hooves and limited fat stores can put pronghorn at risk of death, she said, “but it’s interesting this is carrying over all the way into the summer.” Reinking reckons this protracted vulnerability could be linked to the fact that “pronghorn invest highly in reproduction.” It is very energetically expensive for female pronghorns, she said, which gestate for almost eight months before giving birth to fawns that weigh nearly a sixth as much as their bodies — equivalent to humans delivering 25-pound babies.

“Because these animals are expending more energy through winter and enter that winter in poor condition, by the time they’ve gone through late gestation and lactation, they’re in such poor condition that they can’t sustain survival,” Reinking said. “Even if they’re exposed to high-quality forage in the spring and summer, they still might not be able to offset the impacts of all that expended energy.”

She emphasizes the need for managers “to keep in mind that energetics are important for pronghorn in the context of reproduction and can impact their survival all the way through to the following summer if they experience extreme winter conditions.”

Past research has indicated mature female pronghorn are highly susceptible to death in the summer after gestation and weaning, Reinking said. It has also been shown in other studies that severe snow can lead to mass mortality in the ungulates and that overall precipitation, especially during gestation, closely correlates with their populations’ persistence.

Reinking and her partners have another study underway on the female pronghorn’s resource selection and factors driving disease prevalence. They also plan to assess fawn-to-female ratios in terms of environmental conditions throughout the state.

The Red Desert pronghorn have recently been on the rise with a 2016 population estimate of 35,000 individuals, Reinking said, but they could face trouble as climate change worsens and roads and fences block their escape from increasingly snowy areas and access to high quality resources.

“If we’re experiencing more extreme winter weather, you’re going to see greater die-offs during winter, spring and all the way through to summer,” she said.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.

Header Image: A collared pronghorn stands with her offspring in the summer sagebrush of Wyoming’s Red Desert. ©Melanie LaCava