Share this article

JWM: Study upends management strategy for sage-grouse

A new study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management suggests managers may need to overhaul guidelines meant to protect greater sage-grouse by focusing less on factors like grass height and vegetation cover and more on broad impacts to the landscape.

“I think the focus really needs to be maintaining intact sagebrush ecosystems,” said TWS member Joe Smith, a research scientist at the University of Montana and lead author of the study. Threats like the encroachment of piñon and juniper; the spread of cheatgrass; and habitat fragmentation by energy development, cultivation and subdivisions have bigger impacts on birds than vegetation measures managers commonly use, Smith said. “Those are the biggest drivers, and we’re losing tens of thousands of acres a year to these landscape impacts.”

Sage-grouse (Centrocercus spp.) management guidelines are typically made based on characteristics and measurements of vegetation within a few feet or yards from a nest. Managers take those fine-scale measures and apply them on a large scale — to a pasture or grazing allotment.

But over the years as Smith studied the bird, he began to wonder if the measures he first learned about in graduate school were really working.

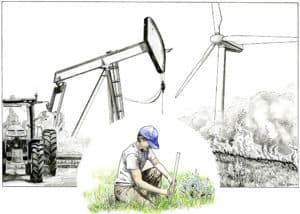

Habitat assessment and monitoring for sage-grouse remains rooted in plot-scale metrics such as height and cover of vegetation, even as our understanding of drivers of population declines has expanded in scale. ©Artwork by R. E. Newton.

“Everything pointed to the importance of grass height and grass cover,” he said. “It was repeated so many times in the literature, I kind of took it as gospel.”

But the research he conducted raised questions. If grass height was so important, then grazing should negatively impact the birds, but that wasn’t what his research showed.

His doubts led him to conduct a meta-analysis of greater sage-grouse research to see if measures like grass height and sagebrush cover really were associated with nest success.

“Fortunately, there had been a ton of these microhabitat studies done in the last 30 or 40 years,” he said.

His team combed research dating back to 1991 to see if these metrics really worked when applied at landscape scales — the scales agencies make decisions on. None of the vegetation characteristics correlated with nest success, they found. These measures that work within a few feet of a nest shouldn’t be extrapolated to the scale of an entire pasture, they concluded.

“We didn’t find any evidence that fine-scale structure of vegetation, either at nests or in the surrounding landscape, made any difference in terms of their success,” Smith said.

It’s not that characteristics like grass height and sagebrush cover don’t matter, Smith said. It’s that the landscapes the birds occupy are highly diverse. They have natural variations that sage-grouse have adapted to, whether it’s limited sagebrush cover in Saskatchewan or heavy cover in the Great Basin.

“They’re making choices as to where to place the nest within the local context,” Smith said. “There seems to be no single ideal recipe that makes good sage-grouse nesting habitat that applies to the entire range.”

That may not be so unusual, Smith said. Researchers writing in the Wildlife Society Bulletin in 2004 found a similar dynamic with northern bobwhites (Colinus virginianus), and management plans based on small-scale features seemed unable to reverse their decline.

Instead of scaling up from microhabitats, Smith said, managers need to start with the large-scale impacts to the landscape to protect sage-grouse.

“We know a lot about how they respond to anthropogenic disturbance — things like oil and gas development, cropland conversion and housing sprawl,” he said. “I think managers should take that knowledge to heart to prevent broadscale threats from eroding habitat.”

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Recent research suggests managers should look at broadscale factors more than fine-scale measures to protect sage-grouse. ©John Carlson