Share this article

JWM: Strictly regulated gator harvest boosts their numbers

Can killing animals within a population actually save that same population?

The question might sound a little ludicrous, but as Mark Merchant, a biochemistry professor at McNeese State University in Louisiana explained, that was what some alligator managers were thinking in the 1970s. The alligator population there was in trouble after decades of persecution and unregulated hunting across the state.

But Ted Joanen, who has since retired from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, persisted in his plan to allow a limited amount of legal harvest in Cameron Parish.

“[The program] was working like crazy,” Merchant explained. “They expanded it and expanded it.”

Early in the process, Joanen invented a locking tag system that would follow an alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) skin from its initial harvest all the way through the process of selling and tanning. It involved snapping a small plastic lock tag with a unique identifying number similar to the type locked onto clothing in stores to stop shoplifting.

Regulators could then check for these tags when inspecting processing sheds or tanneries in Louisiana. Officials finding skins found without tags indicating the gator had been illegally harvested had the power to close processors or tanneries.

Tags used to track legally harvested alligators in Louisiana. Courtesy of Ted Joanen

“The Invention of that locking tag was extremely important,” Merchant said. “You shut that illegal market down.”

Those same tags have also provided decades of solid data on the status of the state’s alligator population. In a study published recently in the Journal of Wildlife Management, Merchant, Joanen and others analyzed those data to find how gator hunt regulation has affected these numbers.

“Alligators can be managed as a sustainable resource, but you’ve got to conduct your hunt correctly,” Merchant said.

While the harvest and tagging program started a few years earlier, the researchers looked at data from 1985 to 2015. They found that the combination of allowing a legal harvest while imposing strict penalties on poaching actually worked to protect the population. At the same time, the sale of gator skins provided an economic boost to a relatively poor state. In that period, more than 870,000 alligators were harvested legally. The total annual hunt right now represents about 3% of the total population, the research found.

“During the 31-year study, the population skyrocketed,” Merchant said, adding that in 1970, numbers were only about 70,000-80,000 in the state. Over the study period, the population increased by 700,000 to 870,000, despite about half of them being harvested. This increase likely has to do with a combination of factors.

“By putting a price on the alligator’s head, it has caused landowners to take better care of their marsh,” he said, adding that this land conservation also provides benefits for other reptiles, amphibians, birds and a broad spectrum of other animals. “A marsh that’s good for alligator is also good for all the wildlife, and particularly for the estuarine fish and invertebrates that uses it as a nursery area.”

The harvest regulations also discourage the harvesting of adult females. Removing males has less of an impact on the population.

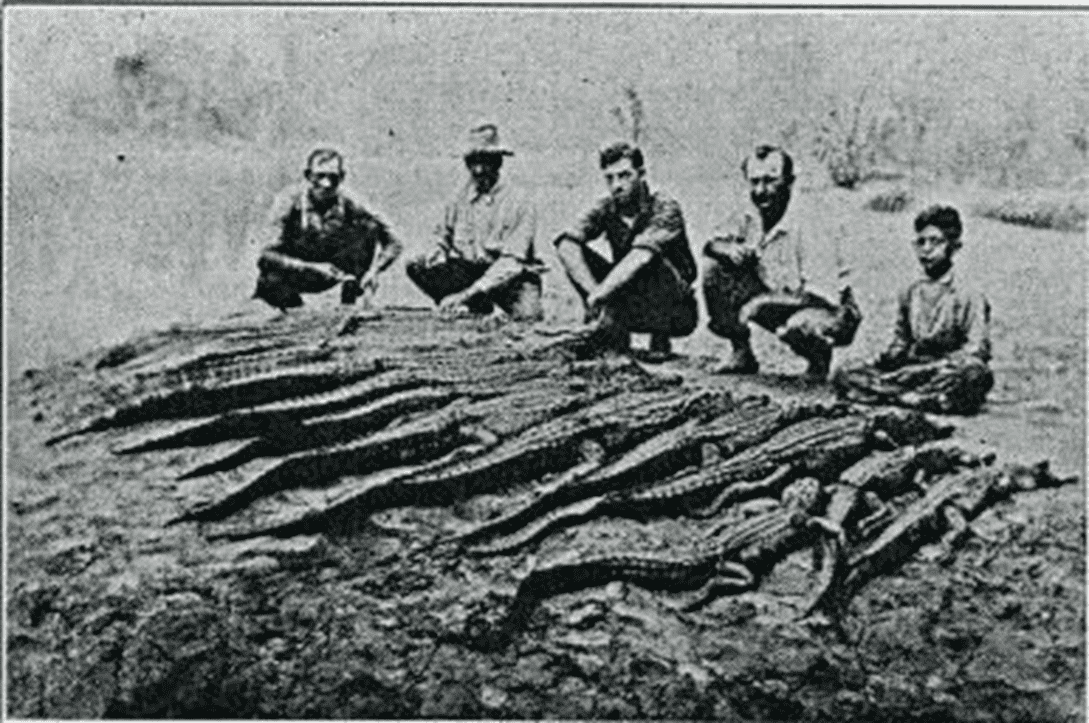

Before the 1970s, the alligator harvest was unharvested, such as in this undated photo. Courtesy of Ted Joanen

The team also found that the size of alligators hasn’t been impacted. Critics had initially believed that allowing the gator harvest might ruin the demographics of the population, as hunters would be more interested in poaching large individuals with more valuable skins.

“It turned out that the population structure stayed stable over that 31-year period,” Merchant said.

This likely has to do with a non-selective hunting method. While hunters might favor areas with larger reptiles, the method of hanging a piece of chicken and waiting for whatever gators jumps out of the water to bite means they can’t easily single out large individuals.

The legal harvest has also resulted in a proportional drop of poaching, Merchant said.

“The alligator population exploded more rapidly than citations for illegal hunting ,” he said.

Another factor that has helped to reduce poaching is that legal hunting is only allowed during the day, making it easier for wildlife officers to police.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: An alligator harvest in the past in Louisiana. Courtesy of Ted Joanen