Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- black bear

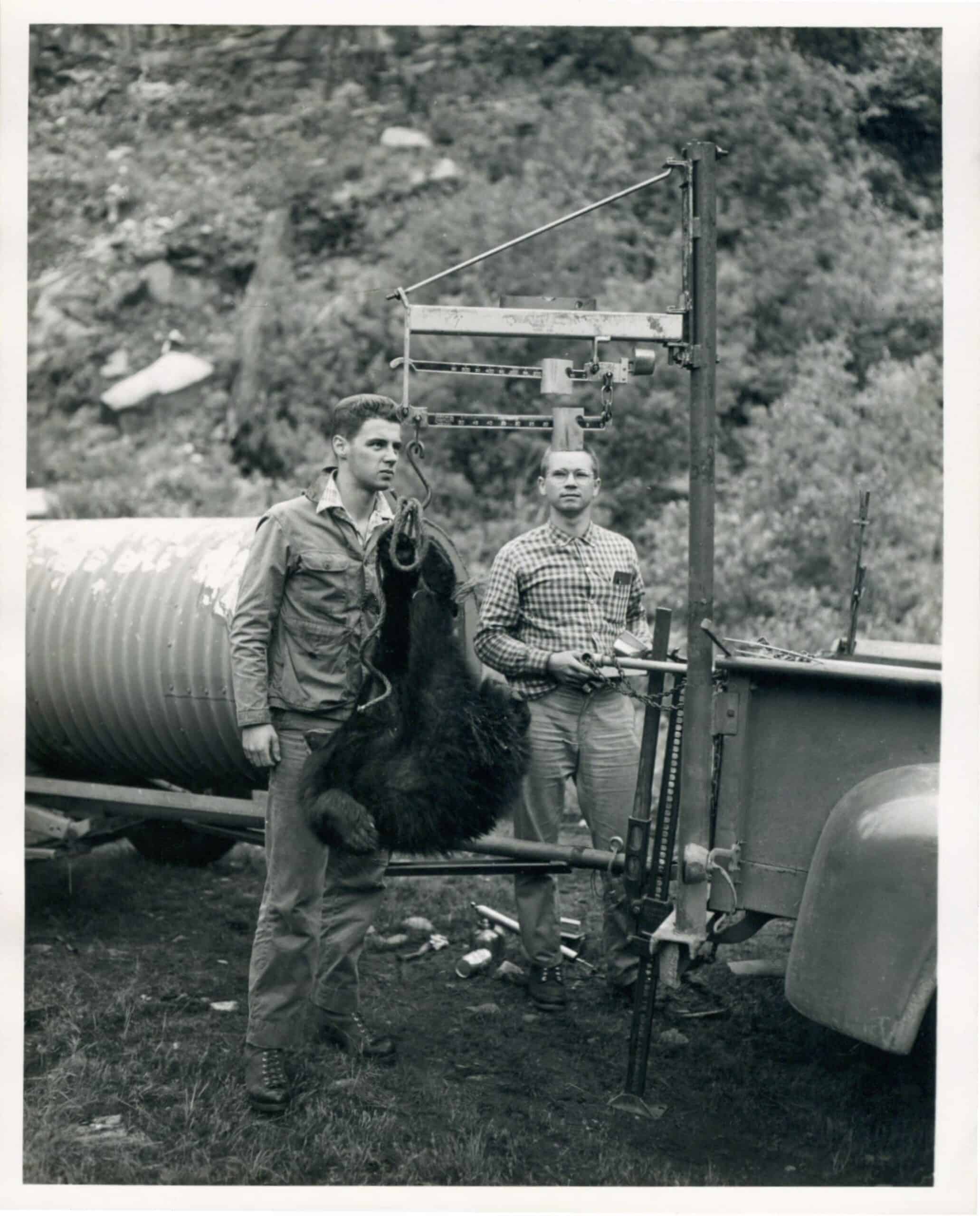

JWM: Bear hunting doesn’t decrease conflict in Ontario

The number of reports about human-bear conflict actually increased in some areas after a pilot bear hunt was reinstated

A sustainable level of black bear hunting doesn’t reduce the amount of conflict that humans experience from the predator, according to new research in Ontario. In fact, conflicts actually increase in some areas where hunting occurs.

Spring bear hunting in Ontario was banned in 1999. In 2014, a small pilot hunt began in eight wildlife management units in areas that had experienced high levels of human-bear conflict. There was likely more conflict in these areas because they were close to larger cities in northern Ontario like Thunder Bay, North Bay, Sudbury and Timmins.

Some wildlife managers believe hunting is a potential way to decrease conflict between humans and black bears (Ursus americanus). Joe Northrup, a research scientist with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, and his colleagues wanted to see if this was true in Ontario. They compared bear-human conflicts before and after hunts were reinstated. They also compared hunted areas with those in other areas that hadn’t reinstated a spring hunt.

For a study published recently in the Journal of Wildlife Management, the researchers gathered information from Ontario’s Bear Wise reporting line—a phone number where people can report sightings or interactions with bears. They searched for reports considered conflicts, where bears attacked pets, or acted aggressively to humans or property. They divided these into the wildlife management units where they occurred, including areas without spring hunting and areas that had restarted the spring hunt. All areas still had a fall hunt. They also looked at natural resource availability—how much food the bears had in a given year.

An analysis of bear conflict going back to 2004 revealed that food availability was the “big driver” for reducing conflict between bears and humans, no matter whether there was a hunt or not, Northrup said.

“When there’s more food, bears are staying away from people,” he said. With less food came more conflict.

When they compared the eight areas with pilot spring hunts to other areas without them, they found that the amount of conflict was higher in areas with bear hunting. Conflicts also increased in 2014 and 2015 in the eight areas with spring bear hunting after the pilot program was instated.

“We don’t know if [the spring hunt] caused those conflicts, but it certainly didn’t reduce them,” Northrup said.

The researchers aren’t sure why conflicts increased, but they have a few theories. One is that hunters in these areas use bait. As bears became used to eating human-subsidized food, it’s possible that they started to seek it out more.

Another possibility involves the social dynamics of bears. Since bears were naïve to spring hunting in these areas, it’s possible that older bears were killed at a larger ratio than they otherwise would be in areas where bears have become leerier of humans due to hunting. As a result, younger bears more likely to get into trouble with humans may have become more common in the eight areas with spring hunts.

Finally, it’s possible that the increased media focus on bears after the spring hunt was reinstated had a social effect on humans, causing more people to phone in reports about bears than they had in previous years, or in areas without hunts. Most of the reports through the Bear Wise phone line were by people that weren’t hunting at the time, Northrup said.

These results also show that hunting—at least at this level—isn’t necessarily going to solve the human-bear conflict problem. Northrup said that most of the research that has found that hunting can reduce human-bear conflict focused on areas that had much higher levels of take than the relatively small percentage in this pilot project in Ontario.

If wildlife managers want to drive down human-bear conflict in these areas, it might be necessary to increase the hunting levels, he added.

The initial pilot hunt was expanded in 2016 to allow spring hunting in all areas that already allowed fall bear hunting.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: A spring bear hunt was reinstated in parts of Ontario starting in 2014. Credit: Werner Bayer