After agricultural and urban expansion fragmented the habitat of the greater prairie chicken (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus) in Illinois and pushed it to the brink of disappearing from the state, translocations between 1992 and 1998 reestablished the species. But a new study warns the birds are declining again and could die off without additional action because the transfer of individuals only increased their population and not their genetic diversity.

“It was an enhancement of the population, not a rescue,” said Michael Douglas, co-author on the paper in Royal Society Open Science. “The chickens are at the same risk of extinction in Illinois as they were 20 years ago.”

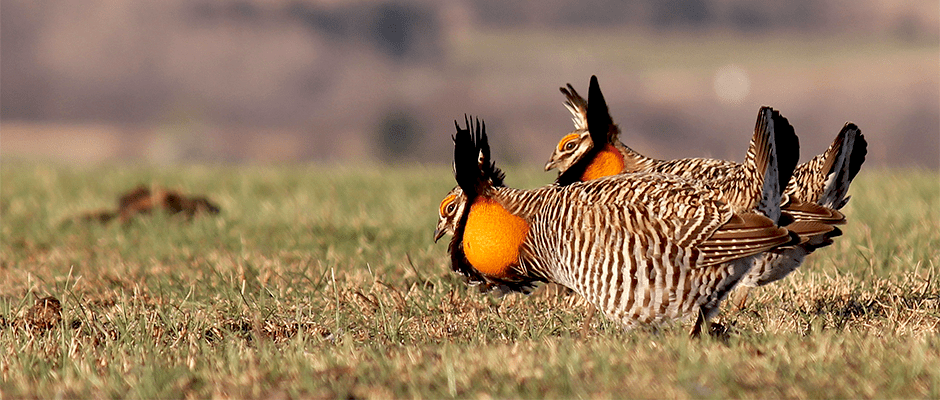

Michael and his wife Marlis Douglas, both biology professors at the University of Arkansas and members of TWS’ Arkansas Chapter, worked with a student in their department; the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Illinois Natural History Survey and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, which funded the research. Between 2010 and 2013, the team examined over 1,800 shed feathers from two separate counties encompassing six leks, small territories where male chickens engage in breeding displays and fight for females. The biologists extracted and analyzed DNA from each feather to determine genetic similarities among individual birds, forming the basis of first author Steven Mussmann’s master’s thesis.

The results revealed decreasing populations, low migration between populations and genetic bottlenecks that contributed to a lack of genetic diversity. Researchers concluded that the addition of individuals in the translocations didn’t boost genetic diversity in Illinois’ greater prairie chickens as intended but simply delayed the potential for extinction in the state.

“It was still beneficial,” said Marlis Douglas. “It bought time. In that sense, it’s a good management tool.”

Habitat loss to farming and development continues to be the biggest threat to the chicken in Illinois, she said, and protected areas are too few and small to support greater populations. “The best way to promote genetic diversity is to increase the population. But to have a larger population, we would need more habitat.”

To secure the species far into the future, Michael Douglas suggested building coalitions to conserve the prairie and strengthening government programs that rehabilitate farmland, augment habitat and focus recovery efforts elsewhere in the state. Already a state-listed species, the chicken could also benefit from being designated as a distinct population segment under the federal Endangered Species Act, he said.

In 2014, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources began moving more birds into the state from Kansas. Once it’s done, the Douglases and their colleagues plan to carry out a similar study to assess the effectiveness of this set of translocations.

“The greater prairie chicken has long been an icon on the prairie in Illinois, something that people who feel strongly about the natural heritage of the state have been dedicated to,” said co-author Mark Davis, conservation biologist with the Illinois Nature History Survey and member of TWS’ Illinois Chapter. “This research underscores that without a sea change in how we approach conservation, these translocation actions every quarter century are going to be necessary to the persistence of the chicken in Illinois. It’s my hope that it’s going to help shape how we conserve habitats and these birds so subsequent generations can see chickens on the prairies in Illinois.”

Article by Julia John