Share this article

Even snowbirds may feel the heat

Heat may stress out snowbirds, despite the fact that they live in areas most people would consider cool at best. As climates continue to warm, this type of stress may be on the rise, possibly resulting in population level impacts.

“It’s very possible that the birds can become heat stressed in the Arctic,” said Ryan O’Connor, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Quebec at Rimouski and the lead author of a study published recently in Ecology and Evolution.

Researchers had conducted heat tolerance studies before on species that may be impacted by climate change. But O’Connor said most of these studies were focused on desert birds that experienced much hotter temperatures.

O’Connor and his supervisor François Vézina had noticed some heat responses in a captive population of snow buntings (Plectrophenax nivalis) — a bird typically associated with cold temperatures in the Arctic, although a few populations live in high elevation mountainous areas south of the Arctic Circle such as the Cape Breton Highlands in Nova Scotia and the southern border area between Yukon and Alaska. Snow buntings are the most northerly known perching bird in the world.

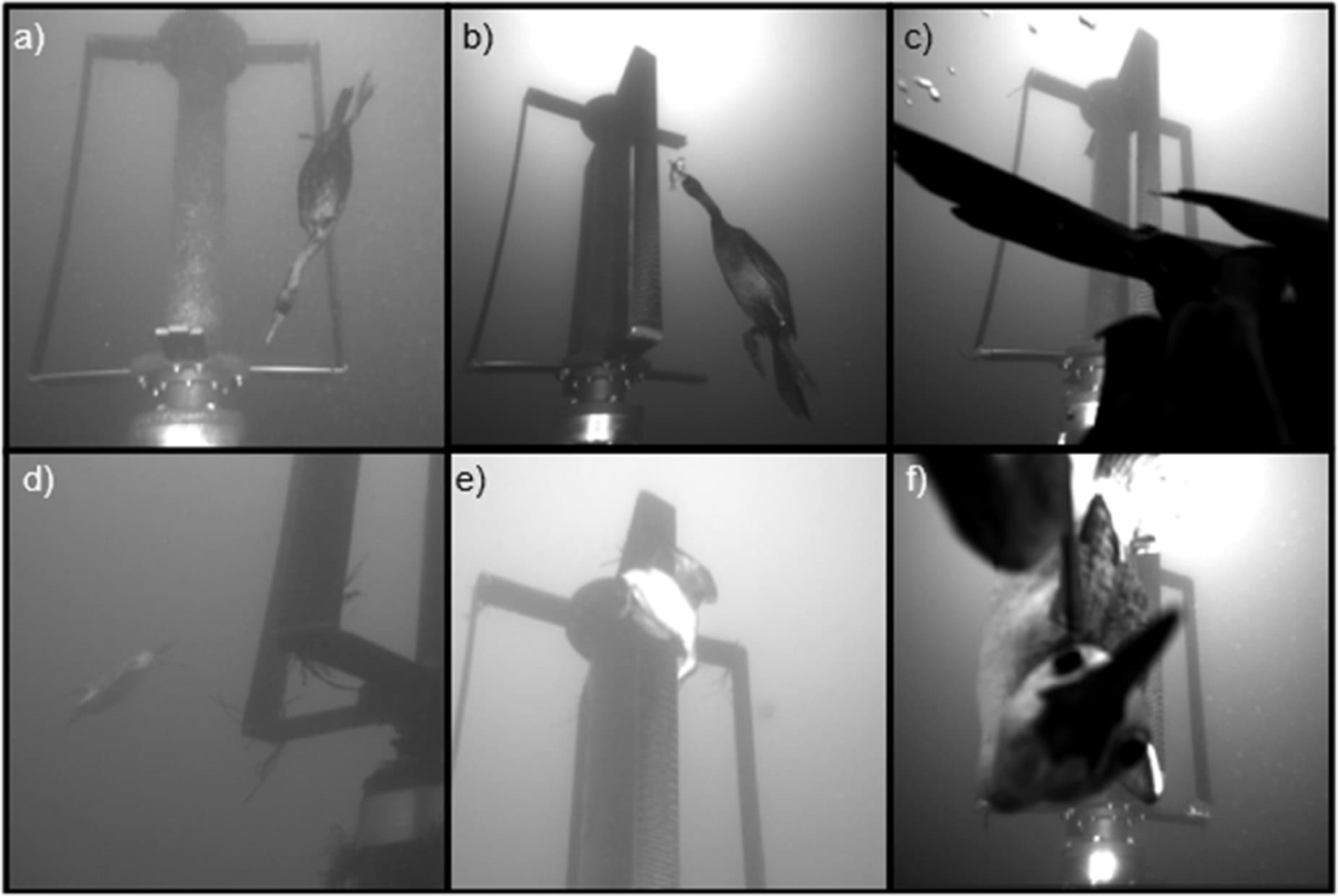

Snow buntings are the northernmost known perching bird. François Vézina

As part of a larger research project studying how global warming affect the range limits of Arctic animals, the team developed experiments in which they put wild birds from the Arctic in controlled containers and manipulated the temperature inside. They could detect all gases going in and out of the containers, whether oxygen, carbon dioxide or water vapor. This helped them determine at what temperatures the birds begin to significantly increase water loss — a sign of heat stress.

They found that snow buntings begin to lose significantly increasing quantities of water at much lower temperatures than more southerly, heat tolerant species. Most of the latter typically begin to lose water, through evaporation, when the temperature of their surroundings is the same as roughly their body temperature, which ranges from 38 to 41 degrees Celsius. But the buntings began to lose water when the surrounding temperature was only 34.6 degrees Celsius.

While that temperature may seem higher than Arctic temperatures even in the summer, O’Connor noted that other factors like solar radiation will increase the actual temperature the buntings experience. And the birds the team studied were sitting still in chambers, whereas being active typically increases body temperature. These factors together could mean that it might not need to be 34 degrees Celsius on a thermometer in the Arctic for the birds to experience heat stress.

They also found that the snow buntings couldn’t manage the heat they were experiencing as efficiently as other birds. “When the birds are heat stressed, they’re going to have a much harder time losing [heat] than any of these other species,” O’Connor said.

More research would be needed to determine whether heat has an effect on their behavior, but studies in some southern species show that heat-stressed birds will spend more time sitting still and cooling down and less time foraging for food, either for themselves or their nestlings. If the latter case is occurring with snow buntings, it could lead to less reproductive success over time as nestlings aren’t fed as well. This could cause population level impacts as the climate continues to warm.

“Over many seasons this might impact population,” O’Connor said.

Header Image:

Snow buntings may experience heat stress at lower temperatures than more southern bird species.

Credit: François Vézina