Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Prairie rattlesnake

- Mojave rattlesnake

Do hybrids hunt differently than Mojave or prairie rattlesnakes?

Tracking venomous snakes in New Mexico, researchers detected differences in hunting behavior

They’ve got mixed genes and a wicked mixture of venom. But despite all these traits, hybrid individuals that come from Mojave and prairie rattlesnake parents seem to fare less well when it comes to body condition.

“The hybrids might be a Jack of all trades, master of none,” said Dylan Maag, a postdoctoral researcher and adjunct biology instructor at San Diego State University about hybrid venom.

Mojave rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus) are found in desert scrubland in the southwestern deserts of the U.S., while prairie rattlesnakes (C. viridis) live in short-grass ecosystems spanning from southern Canada to northern Mexico. These two ecosystems often intersect in parts of southwestern New Mexico, between the Peloncillo and Animas mountain ranges. In these areas, hybrids sometimes occur between these two species.

“It’s been known that there are these weird snakes out in this area for quite some time now,” Maag said. But not a lot of research has been conducted on the natural history of these hybrids. During his PhD research, Maag set out to learn more about the ecological niches that these hybrid snakes occupy and how it compares to those of their parent species.

As part of a study published recently in Ecology and Evolution, Maag and his colleagues captured 189 snakes and implanted 51 of them with radiotelemetry devices. They also measured the snakes and took tissue samples to determine whether they were hybrids or one of the two parental species.

The team then found the snakes’ ambush locations at night and placed cameras nearby, so they could assess prey types and hunting success.

The resulting videos showed that the Mojaves spent more time probing while in their nightly ambush coils than prairies or hybrids. While awaiting prey, rattlesnakes mostly rest their head on their outer coils and sit still. But they occasionally move their head around a little, flicking their tongue out to smell their environment. Researchers believe the snakes do this to periodically reevaluate their ambush position, Maag said.

They also found that prairie rattlesnakes abandon their ambush spots later in the morning than the other two groups of snakes.

In both probing and ambush abandonment, the hybrids really didn’t differ too much from their parent species.

However, the researchers’ analyses revealed that the hybrids were in much worse body condition, overall, than either the Mojave or prairie rattlesnakes. They were typically thinner and smaller, on average. But it wasn’t exactly clear why.

One factor affecting poorer body condition of hybrids may be the snakes’ success capturing prey after envenomation. Due to the fact that the cameras are stationary, and the snake must leave its ambush position to find the prey after it has run off and died, the researchers could only capture the initial envenomation of prey. This means that the actual consumption wasn’t captured on camera. So Maag said it’s possible that while the hybrids didn’t seem to do worse in successfully striking prey than the other rattlesnakes, their ability to gain a meal from their efforts may not have ultimately been as successful. “Maybe the hybrids are worse at finding carcasses,” he said.

Just the same, he’s not certain this is the only possibility for what’s causing the poorer hybrid body conditions.

“More likely, what is going on is that there is some type of physiological difference where the hybrids are not getting as much energy from their food sources as their parents,” Maag said.

For him, the interesting thing about this study is that it reveals how similar these distinct species are, while also displaying the importance of closely monitoring individual animals in their natural environments in order to capture subtle differences. Hybrid zones can provide great natural laboratories for understanding questions about evolution and speciation, he said.

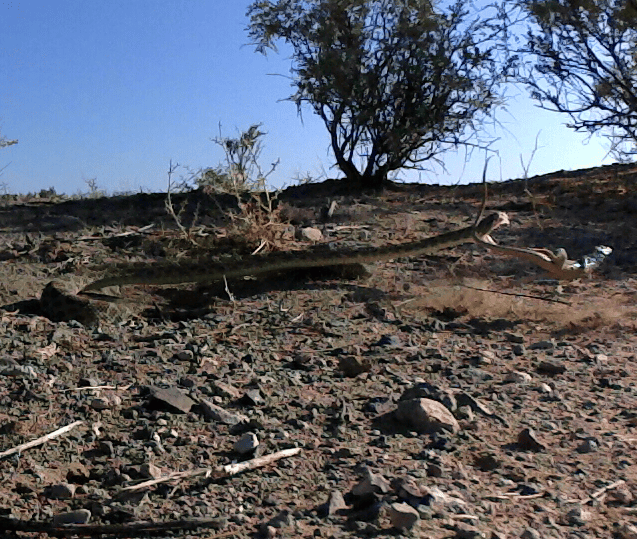

Header Image: Mojave rattlesnake on the left, a prairie rattlesnake on the right and a hybrid between the two in the middle. Credit: Dylan Maag