Share this article

Climate warming changes bird migration timing and body size

Climate change has likely caused migratory birds’ bodies to get smaller and their wings to get longer over the years, and the timing of their migrations has shifted substantially.

Researchers determined this by tapping into a one-of-a-kind dataset from the Field Museum in Chicago. Since the 1970s, museum staff and volunteers have collected migrating birds that crashed into Windy City buildings. One researcher—Field Museum ornithologist David Willard, now the collections manager emeritus—recorded body size and wing length of every single dead bird, where the crash occurred and when. Together, this effort resulted in nearly a half-century of data on more than 70,000 individuals of 52 migratory bird species.

That helped a team of biologists add to a growing body of research suggesting that climate change has affected the size and shape of a variety of species. In their latest study, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, the team revisited those findings by looking at how changes in body size were related to changes in migration timing.

“For the first time, we were able to use these birds that collided with buildings to measure shifts in migration phenology, that is. when birds migrate to and from their breeding grounds across the northern United States and Canada,” said Marketa Zimova, an assistant professor at Appalachian State University and lead author of the study.

In a previous study, published in 2020 in Ecology Letters, Brian Weeks, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Zimova, and other co-authors extracted information from the dataset on body size and wing length for species such as dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis) and white-throated sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis). They found that over 40 years, bodies generally got smaller and wings got longer. When they overlaid this with climate information, they found a clear pattern. Periods of rapid warming were followed closely by periods of body size decline.

Some of the birds collected at Chicago’s McCormick Place, a convention center, include an eastern meadowlark (Sturnella magna) and an indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea). Credit: Field Museum, Karen Bean

“This amazing dataset of more than 70,000 migratory birds was perfect to test the hypothesis that animal body size is declining in size in response to climate change.” Zimova said.

In this more recent study, the team looked at migration timing in relation to these changes. They found that spring migration got earlier by about five days over the years, while the timing of fall migration broadened. “The earliest migrants are now departing their breeding grounds earlier, while late migrants are flying even later than they did 40 years ago,” she said about the fall migration. “As a result of this, the duration of fall migration has stretched out by about 17 days.”

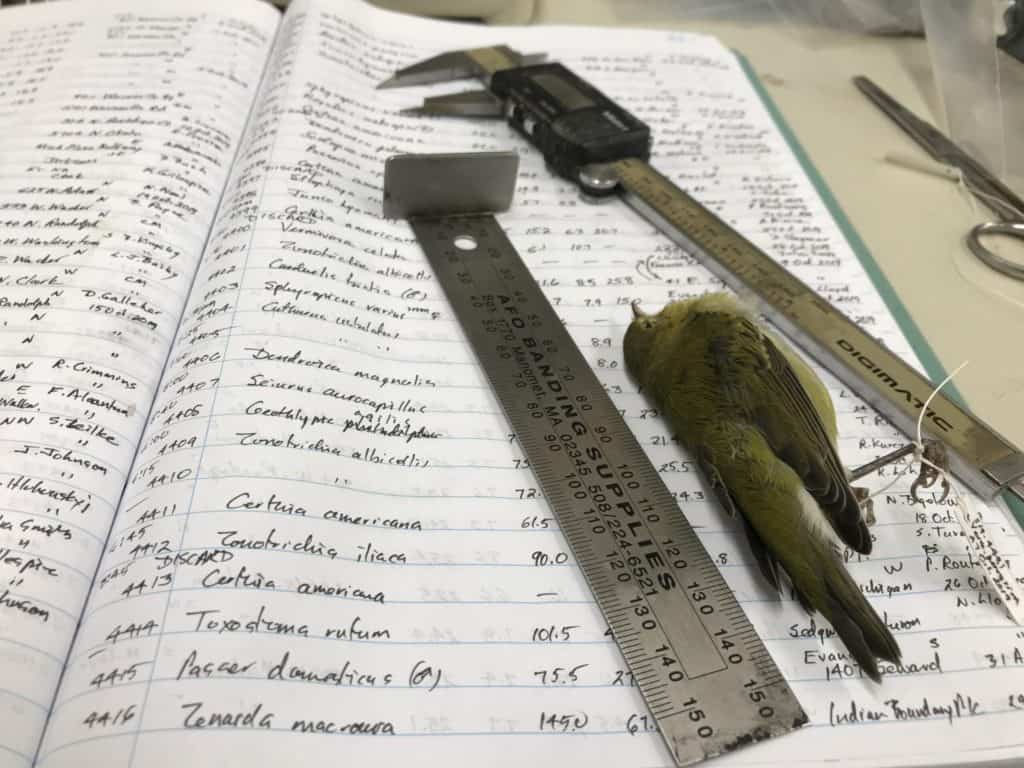

A handwritten ledger in which Field Museum ornithologist and collections emeritus David Willard tracks bird data. Credit: Field Museum, Kate Golembiewski

The team went on to investigate whether the widespread shifts in migration phenology were related to the observed shift in migration timing. “One of the most common responses to climate change are shifts in migration phenology—flowers bloom earlier in the spring or animals migrate to their breeding grounds earlier. And so we hypothesized that the pressure to advance spring migration resulted in the morphological shifts we observe in these birds,” Zimova said. “For example, longer wings are associated with faster and more efficient flight. Therefore, we predicted that species that exhibit the greatest increases in wing length were the ones that advanced their spring migration the most. However, we didn’t find this relationship.”

Instead, the team reported that the widespread morphological and phenological shifts across the 52 species of birds are occurring independently of one another.

Zimova said that this was a surprising result. “Given that bird morphology and flight are so tightly linked, we suspected that widespread shifts in both of these dimensions would be connected in one way or another. But they are not, which only suggests that animal responses to climate change are lot more complex than we tend to think.”

Header Image: Field museum ornithologist and collections manager emeritus David Willard measured all of the more than 70,000 migratory birds analyzed in the study. Credit: Field Museum, John Weinstein