Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Mexican long-nosed bat

Can bats and tequila coexist in Mexico?

Researchers explored incentives to make tequila more bat friendly

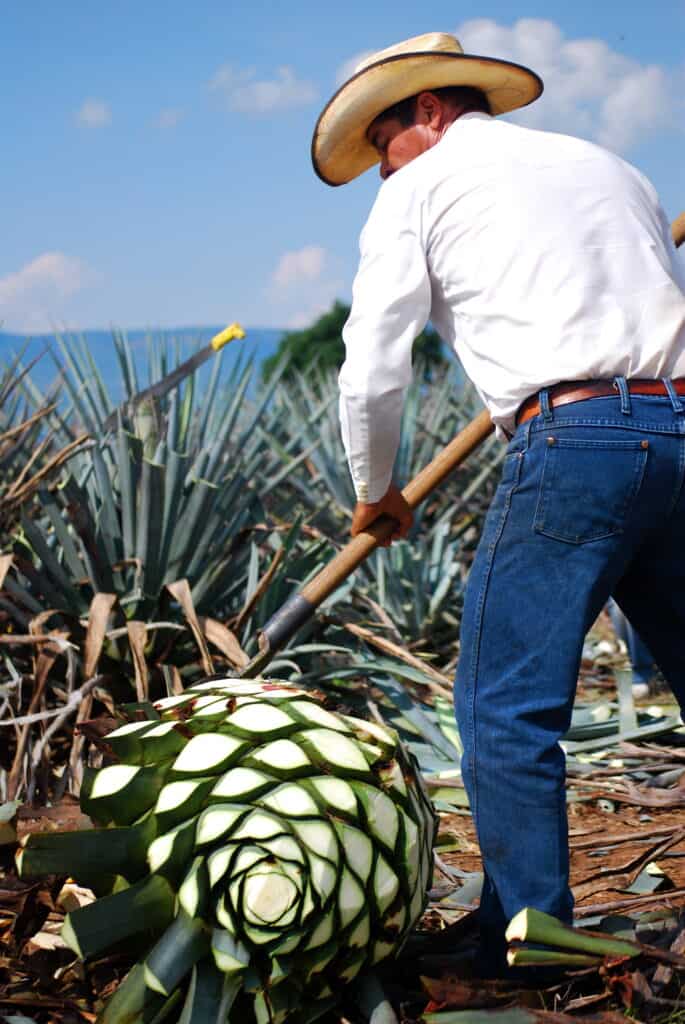

When Mexican farmers harvest agave for tequila before the plant flowers, bats don’t have a shot at pollination.

The core of the plant, which looks something like a pineapple, is what’s used to create tequila. All the sugar needed for fermentation is concentrated there. Because agave puts all its energy into producing its towering, flower-filled spikes, farmers collect the cores before the plants bloom. Once the agave flowers, it dies.

But bats, like the Mexican long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris nivalis), need these flowers to feed.

Irene Zepata-Moran, a PhD student at the University of Wyoming, led a study published in Environmental Research Communications looking at how to balance the needs of blue agave farmers with the needs of bats and biodiversity.

Some tequila producers who cultivate their own agave do leave plants aside to benefit bats. That allows them to place special holograms on their bottles to show consumers that they are bat-friendly—and to charge more for an environmentally friendly product.

But many farmers don’t produce their own tequila. They supply their crops to tequila houses. For them, there’s no incentive to let plants flower.

To find out how farmers can be involved in more sustainable agave production, Zepata-Moran interviewed farmers and tequila producers and provided them with a choice experiment.

She offered them a series of hypothetical options. Would they enter into a program to leave part of their crops untouched for monetary incentives? What about nonmonetary incentives, like training to use greenhouses to grow seeds produced by bat-pollinated flowers? Would they enter into a program to increase their crop yields?

Currently, farmers grow new agave by using clone offshoots or planting a clipping from another plant. But leaving some plants untouched and letting bats do the work can increase the genetic diversity of the plants and improve the health of the crop.

“Genetic diversity in blue agave crops has decreased over time,” said Zepata-Moran, who completed the study as part of her master’s dissertation. “What happens when we don’t have genetic diversity in the population is they are more prone to diseases.”

In general, the farmers preferred monetary incentives. “They like to be compensated,” she said. In this scenario, farmers would be paid for the plants they couldn’t sell to tequila producers because they let them bloom.

They also had a willingness to let plants flower if it increased their yield. Zepata-Moran said she heard from some longtime farmers who were seeing smaller plant cores and other problems, likely due to low genetic diversity.

Before strategies like these could be put into place, Zepeta-Moran said, there needs to be more research on the role this iconic crop plays in the farmers’ heritage and how their yields could improve with more bat-friendly techniques.

“There is a cultural value that exists in terms of tequila production and agave production,” Zepata-Moran said. “It’s something that people are proud of.”

Header Image: Bats, including the Mexican long-nosed bat pictured here, help pollinate agave, but the plant is often harvested before it flowers. Credit: Guillermo MuñozLazy