Share this article

Black-tailed deer return quickly after megafire

Black-tailed deer returned to areas burned by the Mendocino Complex Fire in California—in most cases only a few hours after it scorched the area and trees were still smoldering.

Being able to find out how black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) behaved after a large, complex fire required a bit of serendipity. Researchers had been studying the deer, a subspecies of mule deer, in Northern California before the fire struck. They had collared 18 of the ungulates and set up camera traps to monitor their movements.

Then, California’s third largest fire hit half of the study site.

“We obviously weren’t predicting the wildfire to sweep through,” said Samantha Kreling, a PhD student at the University of Washington. “I thought it was a bit cooler than the dataset I was originally working with and my mentors were supportive of me taking on the project, so I began pivoting toward this.”

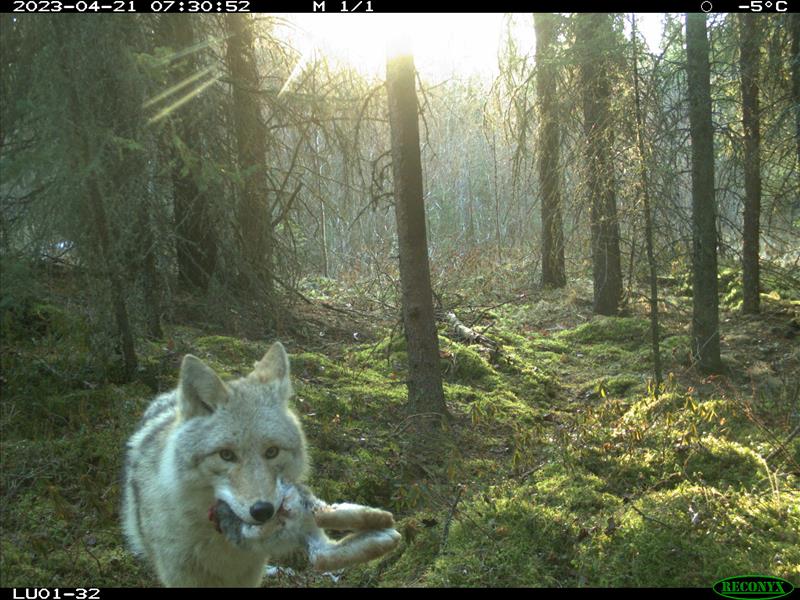

A black-tailed deer at the University of California’s Hopland Research and Extension Center, seen after the 2018 Mendocino Complex Fire. Deer from burned areas had to work harder and travel farther to find green vegetation, and researchers noticed a decline in body condition in some of the animals. Credit: Samantha Kreling

Kreling co-led a study on the impacts of fire on these deer published recently in Ecology and Evolution. To conduct the study, she and her colleagues compared pre-fire data on home range size and movements with post-fire data. Some deer had home ranges that weren’t touched by the fire, while other deer’s habitats were scorched. The researchers looked at camera trap photos to assess how the deer’s body conditions were changing within and outside the burned areas.

All of the collared deer survived, and within a few hours, they began returning to areas that had been burned by the fire. It wasn’t a complete surprise. Biologists have noted ungulates coming back to burned areas, possibly to wait for the new vegetation they like to eat. But Kreling and her colleagues were surprised by how fast they returned. Only one deer took a couple of days, she said. That doe had to travel four kilometers after it was displaced after the fire—a distance much larger than their usual home ranges, which are typically about a tenth of a square kilometer.

A black-tailed deer with her fawn, seen after the 2018 Mendocino Complex Fire. Credit: Samantha Kreling

The team also found deer’s body condition inside the fire perimeter declined compared to those outside of the fire. Its poor condition was likely due to having to work harder and travel farther to find the unburned vegetation. That poor body condition could potentially impact reproductive rates in years following, Kreling said.

While returning to their home range is an evolutionarily adaptive trait that could benefit the species, that may only be true in the sort of frequent, low-intensity fires that historically shaped this landscape. With climate change resulting in more severe and frequent megafires, returning to the areas may no longer benefit them as this fire regime continues, she said.

Header Image: A black-tailed deer wearing a GPS tracking collar on the study site a couple months after the 2018 Mendocino Complex Fire moved through. Credit: Brashares Lab, UC Berkeley