Share this article

Birds shift egg-laying time with climate

Some birds in Chicago are laying eggs as much as 25 days earlier than they did about a century ago.

Researchers say that’s because as the climate warms, vegetation and insects may be emerging earlier, causing some birds to speed up their egg-laying dates to adapt.

“Definitely, some of the species are moving ahead, and most of those are species are in decline—but not all of them,” said John Bates, curator of birds in the Negaunee Integrative Research Center at the Field Museum in Chicago. Bates published these findings in a study he led in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

Working at the Field Museum, Bates often has his hands on natural resource collections. A few years ago, he became interested in a long-running series of eggs. “It’s a collection that’s really underutilized,” he said.

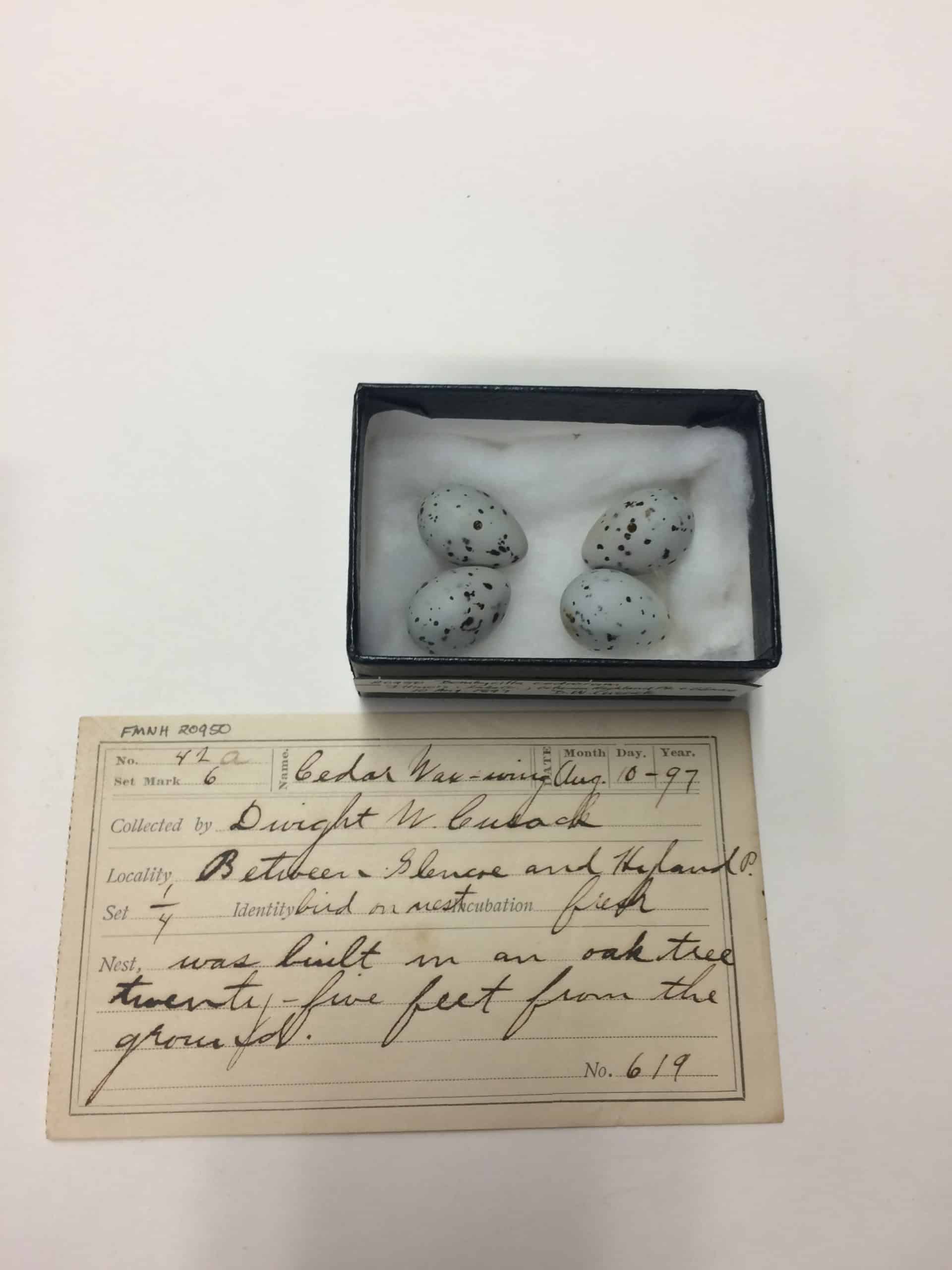

When he first looked into it, he noticed the eggs had paper slips with information on the birds dating back from the 1880s. The information described where people collected the nest and more. “It was very detailed on how far along the clutch was and how may eggs were in the clutch,” he said. Most of those collectors were amateurs, and the natural history museum assembled them largely through private donations. “They were just fabulous natural historians,” he said.

A clutch of cedar waxwing eggs in the Field Museum’s collection from 1897. Credit: Field Museum

Bates wondered if he could use this data to find out how the timing of egg-laying has changed over the years. But the museum data provided only part of the story. As he dug deeper, he found that egg collecting died out in the 20s and 30s, corresponding with backlash regarding the feather trade. “From my perspective, that’s somewhat unfortunate,” he said.

Bates and his colleagues used the information from that period that they could find and developed models to fill in the gaps since the 1920s. But finding more recent data on the birds was also a challenge. Luckily, Bill Strausberger, one of Bates’ colleagues at the museum and co-author on the paper, had been conducting a study on cowbird (Molothrus ater) parasitism for decades. He would go out every spring and monitor nests of different bird species for cowbird parasitism. Another author on the paper, Christopher Whelan, was conducting information for breeding bird surveys. The team was able to compile this data and compare it to the museum data regarding first egg-laying dates.

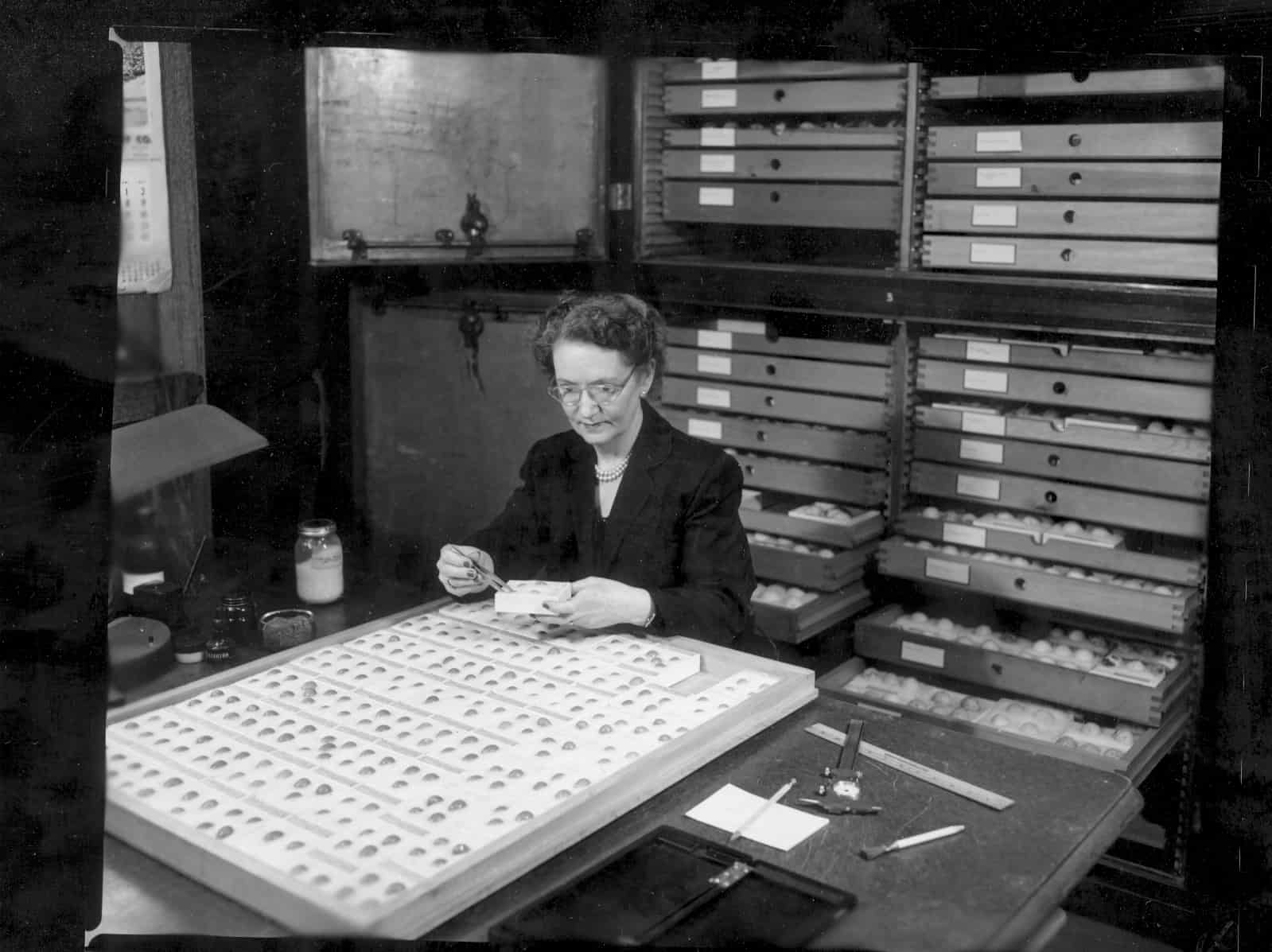

Amateur hobbyists collected eggs from the 1800s to the 1920s. Credit: John Bates

The researchers found that one-third of the birds included in their data sets had moved their egg-laying up by about 25 days. Some of those species included cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum), yellow-billed cuckoos (Coccyzus americanus) and American kestrels (Falco sparverius).

But what was the reason for those changes? Researchers determined climate was a likely cause. Unfortunately, there wasn’t any temperature data dating back as far as the 1800s, so the researchers used carbon dioxide levels, which can be found in things like the chemical composition of ice cores from glaciers. While carbon dioxide levels may not directly affect birds, Bates said high levels correlate with warming temperatures. Their models showed a strong correlation.

Ann McLellan Bigelow works on egg collections in the Field Museum in 1951. Credit: John Bayalis, Field Museum

Bates and his colleagues wondered why some species were affected in this way but others weren’t. They looked at migration distances, thinking that birds with longer migrations may have more difficulty timing their migrations with the changing environments. They thought those birds may not be able to tell what the environment looks like in their distant destination. But that didn’t prove to be true. “Some long distance migrants moved their nesting dates up,” he said.

Many of the species that moved their migration date are also currently in decline, Bates said, but they aren’t sure what the connection is. “I think the key thing is we’re highlighting how much additional research needs to be done,” he said.

But since there was no silver bullet to determine which species’ egg-laying dates would be impacted by climate—and how that may impact bird decline—Bates stresses the need for regional, species-specific studies. “I like to think of our study as a small step in adding to this really difficult puzzle,” he said. “Looking into basic aspects of breeding biology changing, we didn’t see a consistent pattern for long distance migrants or residents being able to track things better. This highlights to me how many variables might be impacting their responses.”

He also stresses the importance of not only collecting, but digitizing and archiving that data. “These guys that collected these eggs in the 1800s had no idea they would be used for a study like this,” he said.

Header Image: A drawer from the Field Museum’s egg collections. Credit: Bill Strausberger