Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Black-winged stilts

- Common tern

- Little tern

- Spur-winged Lapwings

AI cracks the code to monitor mixed bird colonies

An innovative AI system monitors seabird colonies with over 90% accuracy

Researchers in Israel have used artificial intelligence-powered cameras, trained by biologists and computer scientists, to monitor large seabird colonies with precision and efficiency.

“Every year, we would get the question of how many breeders from each species were in the colony,” said Inbal Schekler, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Haifa. “The question was hard to answer and to compare along the years because of the density of the colony, the observation error and the counting method itself, which changed through time.”

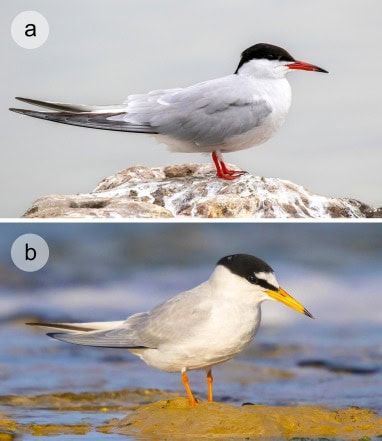

Schekler is responsible for monitoring and reporting on a breeding colony of terns, located on an island within a large salt production facility along the Mediterranean Sea of northern Israel, where approximately 90% of the local breeding population now exists as a single, large, dense colony. Over recent decades, common tern (Sterna hirundo) and little tern (Sternula albifrons) populations in Israel have undergone significant change. The loss of suitable breeding habitats has led to increased aggregation that heightens their vulnerability to catastrophic events such as predation and disease outbreaks, while also potentially intensifying competition between individuals of the same species and with other species.

Accurate data is essential for protecting biodiversity and effectively managing species. Yet traditional wildlife monitoring methods, such as direct observation and counting birds on images, are labor-intensive, prone to human error, and often impractical for densely populated breeding colonies like this one. Although breeding counts were conducted roughly once a week from April to August over the years, different professional observers were in charge over time, and different methods were used, introducing variability and inconsistency into the data collection process.

Schekler and her coauthors wanted to improve the accuracy of counts and turned to collaboration with computer scientists. In their new paper in Ecological Informatics, the team discussed how AI can help overcome errors introduced by human observation without disturbing the colony, as often occurs with traditional monitoring methods.

Creating solutions

The team, led by Eyal Halabi, a researcher at the University of Haifa, and Schekler, trained an object detection algorithm using more than 1,600 labeled images of terns captured by automated cameras.

“The model was successful because we incorporated into our algorithm the same features we use in the field to monitor and distinguish between the species,” Schekler said. The camera-based algorithm was used not only to count birds but also to monitor behaviors like sitting, standing, flying and breeding and map the exact location of every breeding bird in the colony.

The model was trained to recognize species, chicks and occasional nontarget visitors like black-winged stilts (Himantopus himantopus) and spur-winged lapwings (Vanellus spinosus). Crucially, it used behavioral cues, like long periods of sitting during incubation, to distinguish breeding adults from nonbreeders.

When implemented, the AI-powered system mapped daily nest locations, providing high-resolution data on colony structure and dynamics with over 90% accuracy. The model offers a powerful, noninvasive tool for improving seabird conservation and could transform how seabirds in dense mixed colonies are monitored in difficult-to-access or sensitive habitats.

Moving Forward

The success of this framework demonstrates the potential for AI-powered monitoring and the power of collaboration between computer scientists and ecologists. AI has the potential, when trained correctly, to reduce errors and bias, reduce logistical challenges and be cost-effective. Cameras are also able to flag threats like predators and monitor rising water levels that could flood nests. As more conservation efforts seek to minimize the human footprint while maximizing data quality, solutions like this could become essential in the modern conservation toolkit.

Schekler is excited to apply this technology to other issues facing the colony, such as the large mortalities chicks have experienced in recent years.

Header Image: Lead author Inbal Schekler holds a banded bird. Credit: Inbal Schekler