Share this article

Video: Citizen Scientists Help Educate About Endangered Bat

Kirsten Bohn had just moved to Miami to begin working as an assistant research professor at Florida International University. It had been a few days after she had settled into her new house in Coral Gables, in December 2012, and she decided to retreat to her backyard porch shortly after sunset to relax with a glass of wine.

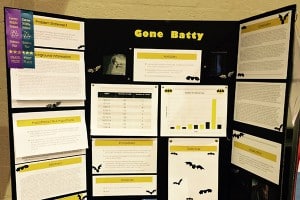

A science fair project by junior high school student Sophie Sepehri displays information on Florida bonneted bats. Sepehri, who tracked bat activity using iPad, won city, regional and state awards for her science project.

Image Credit: Miami Bat Squad

As she sat down, sipping her wine, she heard a familiar sound — “Teek, teek, teek.” It was a high-pitched, sing-songy chirp of the endangered Florida bonneted bat (Eumops floridanus). “These sounds are not usually audible in other species,” said Bohn, now an assistant research professor at Johns Hopkins University, who has been studying other bat species in the molossidae bat family for over a decade. “For me, to hear it calling back and forth in real-time was amazing.”

The Florida bonneted bat, found in southern Florida, particularly Miami-Dade County, hasn’t been studied much, according to Bohn. “We didn’t know where they give birth, what they eat, what their foraging range is, what they’re roosting in. We know absolutely nothing about this bat,” Bohn said.

Soon after she identified the chirps, the Miami Herald ran an article on Bohn’s efforts and the response was amazing: “The public went wild,” Bohn said. “I had 100 e-mails within 24 hours.”

Florida bonneted bats make a unique chirping sound that’s audible to humans unlike many other bat species.

With help from citizen scientists who call themselves the Miami Bat Squad, Bohn was able to uncover some of the unknowns about these Florida bonneted bats or “Eumops,”which Bohn refers to them as, because of their scientific name — the largest bat species in Florida that they now estimate include only 200-500 known individuals.

About a year ago today, Bohn organized a bat night where she educated the approximately 300 attendees about the species over rum supplied by Bacardi — the rum company with its iconic bat logo. Bohn continues to teach citizens about distinct bat sounds and has also introduced individuals to an app for an iPad or smartphone that can pick up high-frequency bat chirps and detect the bats visually. The team recorded more than 300,000 calls, allowing Bohn to explore a wide range of data on the bats that covered a much larger range than had been previously thought. Bohn credits the people of Miami for the increased exposure and interest in the species. “It wasn’t me that started the citizen science aspect; it was the community.”

What They Found

With the data that were recorded, Bohn and her team were able to find one of the bats’ roosts near the main golf course in Coral Gables only four blocks from Bohn’s house. And to find other possible roosts, Bohn had volunteers spread out on a field and record when they heard the chirps. Sounds were coming from the north, east and south, suggesting that there are three other roosts present, Bohn said, although the team hasn’t discovered them yet.

Bohn said one of the main findings from her research is that these particular bats can be studied acoustically. “The problem with most endangered bats is acoustic sampling,” she said. “The bats use ultrasonic signals that don’t travel very far and are easily blocked by interfering objects. We have learned that because this bat uses such a low frequency and produces calls at such high amplitudes, you can hear this bat from great distances. If it’s flying around, you’re going to pick it up acoustically.” With inherent biases about bats needing ultrasonic microphones, Bohn noted that a regular microphone is sufficient and even better to use for this type of bat. Further, the team found that bat surveys for Eumops should not be conducted in the winter, from mid-November to the end of February, because the bats are sensitive to temperatures and only emerge on warm nights.

In the next month, Bohn said she will have a map of all of the “hearings” (rather than sightings) of the bats throughout Miami-Dade county. She also partnered with a community conservation group, Friends of Ludlum Trail, which is working to preserve green space that covers 12 miles from Miami International Airport, all the way south, to determine whether there are more roosting sights close to the trail and if the bats are using the area for foraging. They are also erecting bat houses along the trail, she said, in order to provide habitat for the bats. Bohn is currently in need of volunteers for a future project including collecting guano and using DNA barcoding techniques to determine the bats’ diet.

Citizen Scientists help put up a bat house, as part of their help protecting the endangered bat species in Miami.

“Most people who study bats think they’re just so furry and all so cute, but for me, I felt that this is a world that we didn’t know existed,” Bohn said. “If you sit out in the middle of the night you may not hear or see a thing, but you can turn on the light and there’s a bat. “I like to say that once I started, once I went bat, I never went back.”

Header Image:

A Florida bonneted bat soars through the sky. This bat species is the largest in Florida, with only 200-500 individuals left.

Image Credit: Miami Bat Squad