Share this article

Q&A: The ecology of domestic species versus their wild ancestors

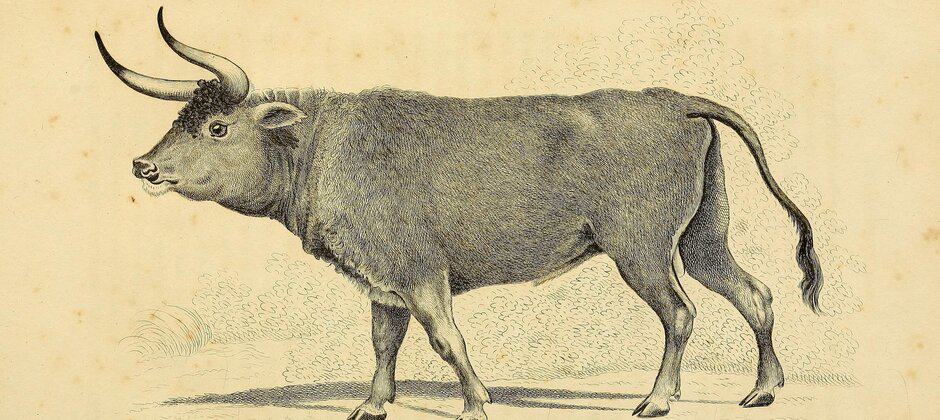

Every domesticated animal on the planet has roots that trace back to a once-wild ancestor. Chickens are derived from red junglefowl. Holstein cattle were once aurochs, an extinct ox.

But while species like junglefowl still roam many parts of the world, aurochs (Bos primigenius) and many of the other wild ancestors of domesticated species have long been extinct. These extinctions can leave a functional gap in many ecosystems, since a herd of cattle doesn’t necessarily fulfill the same ecological roles on the plains as aurochs once did.

In other cases, domesticated species like pigeons have escaped back into the wild after centuries of natural selection have changed them. Those once domesticated species can then interbreed with wild pigeons, irrevocably changing wild populations.

William Smith studies rock doves and domesticated pigeons at the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at the University of Oxford.

Credit: William Smith

The Wildlife Society connected with William Smith, an ornithologist at the University of Oxford, who is the lead author of an essay published recently in Conservation Biology on the topic, to discuss what these various exchanges can mean for species and ecosystems. The interview is edited for style and brevity.

What are some of the wild ancestors of our most common domesticated animals?

There are a diverse set of now domesticated animals that are derived from wild species. I study the wild rock dove (Columba livia), which is the ancestor of the domestic pigeon. Domestic pigeons include pigeons bred for showing or racing, ones that are used in the lab to study animal behavior, and the escaped feral pigeons that you see every day flying around urban areas. Wild rock doves live in sea caves and on mountains, which is quite cool to see when you’re used to watching them eat rubbish and dodge cars in the streets. Other examples of wild ancestors include the extinct wild horses, which roamed Europe hundreds of years ago, red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) that are ancestors of the domestic chicken, which skulk around in the rainforest undergrowth, and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), which take part in the salmon run that’s been featured in documentaries as one of nature’s greatest spectacles.

Smith with a rock dove captured on the tidal island of Vallay, in the Outer Hebrides of the United Kingdom. Credit: William Smith

Why is it difficult sometimes to disentangle domestic species from their wild ancestors?

This is the biggest problem facing scientists studying these animals. When domestic animals escape captivity and become feral, they are exposed to natural selection. Such populations can lose their unusual traits they were selectively bred to exhibit. For example, the fancy ‘Pouter’ pigeons with giant puffy chests bred for shows, don’t survive well in the wild.

As a result, feral pigeon populations start to look quite like their wild rock dove cousins once the more extreme domestic traits are removed from the population. When feral populations mix with their wild relatives, they can interbreed. Extensive mixing of the two groups can lead to the formation of a complex genetic mixture, where individuals exhibit both wild and domestic traits.

In Scotland, the native wildcat (Felis silvestris) has been interbreeding with the feral domestic cat (Felis catus). This genetic mixing has been happening for so long, and across the entire Scottish range of the wildcat, that we have no baseline for pure Scottish wildcat with which to judge the level of hybridization against. This is a big problem for conservation biologists, given that such hybridization is one of the main threats to the wildcats’ persistence. We have to combine both genetic and morphological data to estimate the level of hybridization in different populations.

What are the dangers of genetic flow between domesticated animals and wild animals in terms of ecology?

Hybridization is surprisingly common in nature, and can be a positive evolutionary force. It can introduce genetic diversity into small and declining populations and even lead to the formation of new species. So in some cases, conservationists might actually view it as a good thing.

On the other hand, extensive genetic mixing of two different populations can lead to the genetic replacement (also called genetic extinction) of the rarer one. This is what we’re worried about with many of the wild ancestors. They’re often quite rare, and they are also inevitably closely related to their domestic cousins. This means they’re especially susceptible to being hybridized out of existence. The rock dove, for example, has been replaced by feral domestic pigeons over pretty much all of its original geographic range. We don’t know enough to suggest how such replacement impacts the overall ecology of an environment, but it certainly reduces the diversity of genetic groups within a species. I think it’s also a big shame to lose such entities as they’re important parts of our story as human beings.

Can domestic animals fulfill the ecosystem services their extinct wild ancestors did?

Maybe. In a few cases, as you suggest, the wild ancestor is now completely extinct. For example, the aurochs were the original cattle, found across Europe, Asia and North Africa. They were massive beasts that played an important ecological role as a large herbivore. Today, many nature reserve managers have tried to replace them with various breeds of domestic cattle. This seems to work quite well, but we can’t know for sure what we’ve lost because we know very little about the biology of the aurochs. We know that in some cases (e.g. wildcats and domestic cats) the two forms are quite different ecologically, so it would be unwise to assume that they’re interchangeable. I would argue that the answer to this question is that it’s very species-specific, and that it would be wisest to stick to the precautionary principle and safeguard the wild ancestors where we can.

What is the importance of continued science and research on domestic species and their ancestors?

It’s important to recognize that the distinction of wild and domestic species isn’t straightforward. In some cases, this can get quite confusing. Przewalski’s horse (Equus przewalski) of Central Asia was once held up as the last true wild horse. Populations such as the moorland ponies in Britain and mustangs in the U.S. are of feral domestic origin. However, a genetic study in 2018 suggested that Przewalski’s horses were actually once domestic horses. Now, in a more recent study looking at their bones, researchers have questioned this and are supporting the original theory once more. It’s a good example of the way scientific facts are being continually updated as we gather more data and conduct additional analyses.

Header Image:

An illustration of an aurochs, the ancient wild ancestor of today’s domestic cow.

Credit:

Biodiversity Heritage Library / Printed for G.B. Whittaker