Share this article

Could more Southwest land support more jaguars?

In 1964, a federal control agent with the U.S. government shot and killed the last known jaguar north of Interstate 10 in Arizona.

While some people have spotted the animals south of the highway since then — traveling east to west across the bottom third of Arizona and New Mexico — these forays have been few and far between.

But researchers recently found that jaguars might be able to thrive in a larger portion of the Southwest than where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service considers to be suitable habitat for them.

“If you just move the boundary north of what you’re normally willing to consider, you find a huge block of habitat,” said Eric Sanderson, a senior conservation ecologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society and the lead author of the study published recently in the journal Oryx – The International Journal of Conservation.

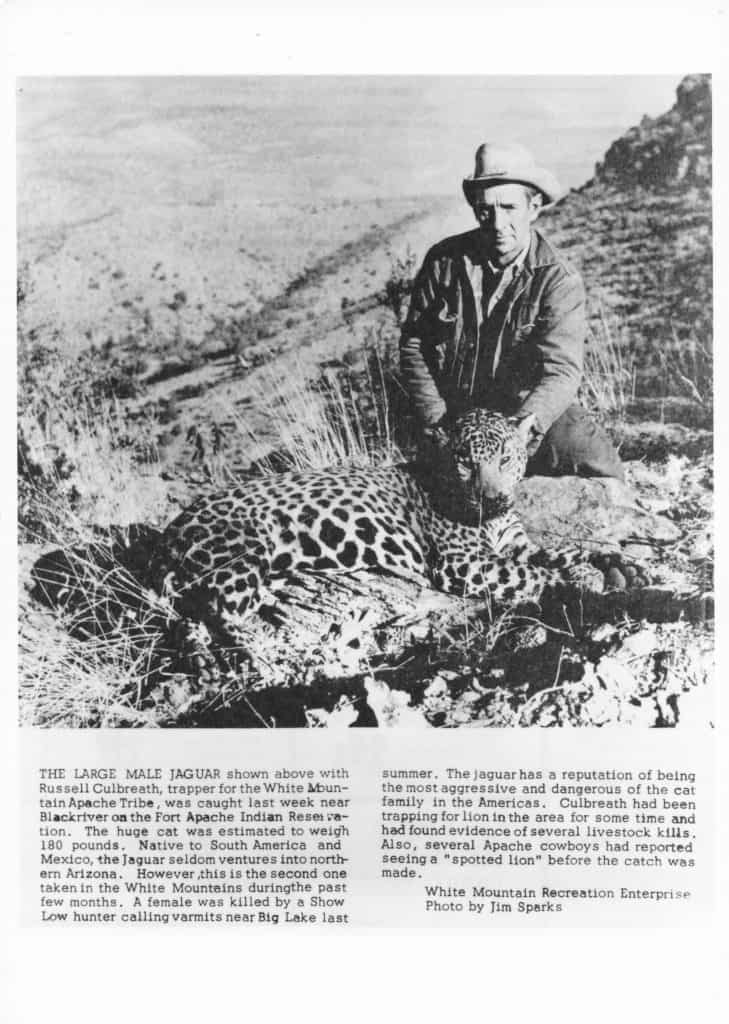

A historic article and photo shows a jaguar killed on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation.

Credit: Jim Sparks

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service created a Jaguar Recovery Unit — a chunk of land south of the I-10 — in 2018 by analyzing the area they believed suitable for the big cats. Most of this area was in Mexico, with only a small stretch of land north of the U.S. border in southern Arizona and New Mexico.

The USFWS didn’t consider land north of I-10 in their assessment, but studies conducted over the past few decades showed that other land in the Southwest may also provide suitable for jaguars.

Sanderson and his co-authors decided to expand their examination of potentially suitable habitat for jaguars by looking north of the interstate. They combined historical records and 12 different habitat models for jaguars in New Mexico and Arizona.

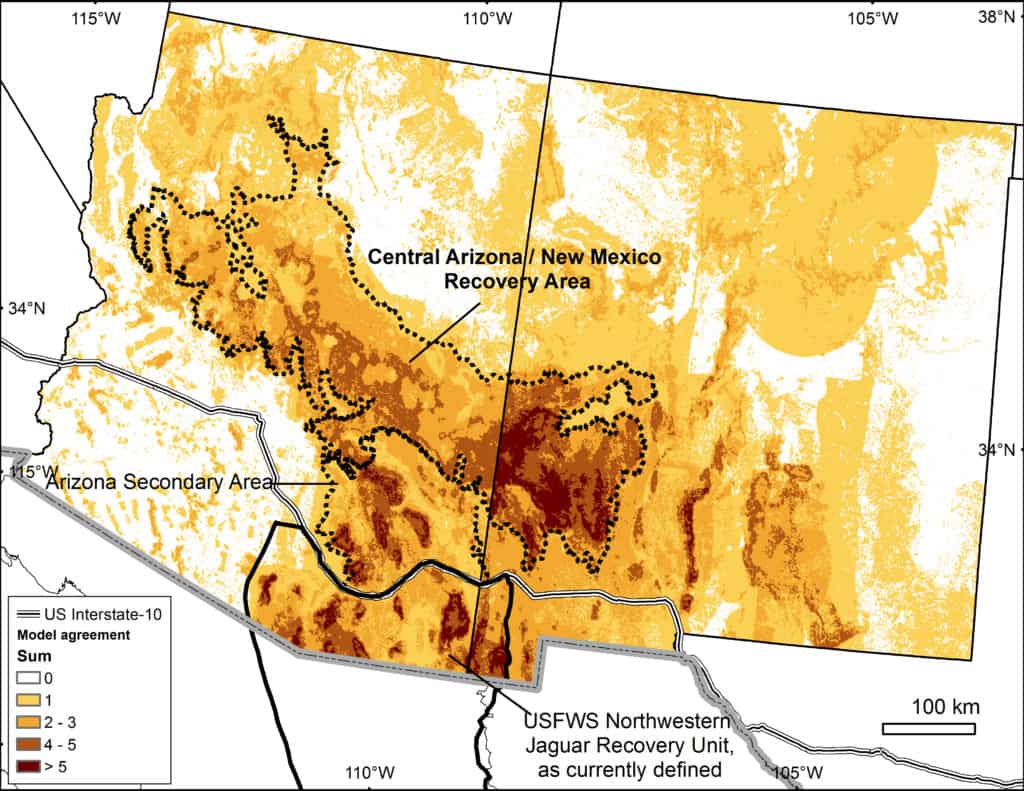

A map that illustrates the potential ecosystem for jaguars found in the new study, as well as the currently defined recovery unit defined by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Credit: Sanderson et. al. 2021

The models showed that a large chunk of land in the Gila National Forest in New Mexico and a larger contiguous piece in wild areas on the Arizona side of the border could support as many as 150 jaguars.

“It’s a very compelling case that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife should move the boundary,” Sanderson said.

TWS member Jim Heffelfinger, the wildlife science coordinator at the Arizona Game and Fish Department, disagrees. He said this new paper “arbitrarily” tweaked suitable jaguar habitat from the 2018 Jaguar Recovery Plan by the USFWS, increasing suitable habitat to an elevation of 2,400 meters from 2,000 meters.

“Increasing Jaguar habitat to 7,800-foot elevation at this latitude in central Arizona-New Mexico is not supported by science for a tropical cat whose distribution centers on the Amazon Jungle,” he said. “This model simply changes the definition of jaguar habitat to include ponderosa pine forests up to 7,800 feet elevation and then proposes we fill that habitat with jaguars.”

He said that some of the previous models compiled in this study are not peer-reviewed and include “unsubstantiated sightings” of jaguars.

“We have 173,000 jaguars occupying habitat from Sonora to Argentina and thousands of species on the [U.S.] endangered species list that need our help,” he said. “Why would we divert precious funds to force jaguars into our snowy pine forests?”

Sanderson said that historical records do show females and cubs in central Arizona, though recent photographs since 1996 have all been males.

A jaguar steps through the snow in southern Arizona. Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

People often associate jaguars with thick jungle, Sanderson acknowledged, but the cats also appear in other landscapes throughout Latin America, from the plains of Venezuela to dry scrubland and pine forests. If the cats have cover, adequate prey, freshwater and a lack of persecution from humans, he said, the cats should do well. Historical sightings indicated jaguars roamed as far north as Colorado and as far east as Louisiana.

“We need to change our thinking about what is habitat for jaguars,” Sanderson said. He sees his paper as “opening up a conversation that will take decades to work through.”

He said that there are potential hurdles to overcome for any future reintroduction efforts. It would need to involve a sign-on from local stakeholders — “if everyone could agree — and that of course is a big if,” Sanderson said.

Another issue would be determining where to translocate the animals from. It’s currently unclear whether jaguar populations south of the border are healthy enough to support the removal and relocation of cats.

Header Image: A jaguar appears on a trail camera image in southern Arizona. Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service