Share this article

From Beauty to Beast ⏤ from The Wildlife Professional

Managing mute swans in Michigan to protect native resources

They were introduced in the United States to grace ponds on private estates and municipal parks. But since their arrival in Michigan in the early 1900s, elegant Eurasian mute swans (Cygnus olor) have spread to the wild, becoming a rapidly reproducing menace in the Great Lakes ecosystem.

By 1990, escaped birds produced a feral population of over 2,000. And over the following decades, the population continued to grow exponentially, reaching an estimated 17,520 birds in 2013. That number was unacceptable, regional wildlife managers agreed.

Michigan Department of Natural Resources biologists knew they had to do something about the invasive species. The large birds were harming habitats and native waterfowl. Given its central location in the Great Lakes ecosystem, the state serves as a source population for Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Wisconsin and Ontario. For a region-wide control program to work, they knew it would take an aggressive plan to mitigate the damage.

In 2006, the MDNR requested assistance from United States Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services. During the development of an integrated mute swan damage management program, our team evaluated a variety of management alternatives intended to control the population.

Impacting habitat and wildlife

Overabundant mute swan populations negatively impact habitats maintained as food and cover for migrant waterfowl and other wildlife. Each 25-pound swan, with a seven-foot wingspan, can uproot 20 pounds and consume up to 8 pounds of submerged aquatic vegetation daily.

In the Great Lakes region, their diet overlaps with many native waterfowl species. The cumulative impact of hundreds or thousands of mute swans can devastate submerged vegetation beds, particularly during ice-over conditions when grazing pressure is concentrated.

In Michigan, a primary concern is their impact on state-listed threatened and endangered species, including trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator) and common loons (Gavia immer). Mute swans, known for highly territorial behavior during the breeding season, can cause conflict with humans and displace native waterfowl from preferred nesting locations.

Because mute swans establish territories and begin nesting about three weeks earlier than the native swans, their presence also may negatively impact the trumpeter swan recovery program. Mute swans also can kill adult and juvenile ducks and geese while defending their territories, and they have destroyed the nests of other bird species of special concern, including the black tern (Chlidonias niger), the common tern (Sterna hirundo), and the sandhill crane (Grus canadensis).

Getting to work

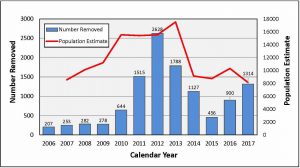

The graph shows the number of mute swans removed by Michigan Wildlife Services from 2006 to 2017 and MDNR state population estimates. Additional funding provided by the GLRI since 2011 has helped the state make progress toward its established a goal of less than 2,000 mute swans by 2030.

Wildlife Services’ control activities prioritized lethal removal (shooting) of adult birds, combined with nest destruction to prevent eggs from hatching. We began initial management efforts in 2006, but the small number of birds removed annually allowed for continued mute swan population growth in subsequent years.

In 2010, the MDNR incorporated population modeling to help inform management efforts and drafted policy and management goals to guide the reduction of mute swan numbers throughout Michigan. The department’s model indicated that reproductive rates would need to be reduced by 55 percent to stabilize the mute swan population. Adult survival would have to be reduced by 11 percent to achieve the same result.

These estimates suggested that, in this long-lived species, removal of adult birds is the most effective method of population reduction. The MDNR estimated that 1,500 adult birds would need to be removed annually to stabilize population growth by the short-term 2016 goal, and 2,800 would need removed each year to reach the state’s long-term goal of less than 2,000 mute swans by 2030.

Since 2011, teams have removed 9,728 mute swans from Michigan, and the population has declined in recent years, to an estimated 8,133 birds. Continued management efforts have helped keep the population lower today.

Expanding efforts on other waterways

A native trumpeter swan flies above a large group of mute swans wintering in the Detroit River during January 2017. During ice-over conditions, flocks of more than 1,000 mute swans congregate in areas of open water where they directly compete with native waterfowl for limited food resources. ©Randy Knapik, Michigan State University/MDNR

Mute swan nest destruction has expanded each year as more private inland lakes and municipal waterways have enrolled in Michigan’s voluntary program. When lethal control is impractical due to safety concerns, or is not desired by the landowner, nest destruction is recommended as a form of localized population control.

During the 2017 breeding season, our teams destroyed a total of 44 nests containing 284 eggs. Sites enrolled in the nest destruction program have reported a reduction in their local mute swan population and less aggressive behavior of breeding birds with no young to defend.

Even more importantly, observations of state-threatened trumpeter swans have also increased throughout Michigan, particularly at sites where mute swan control has been conducted. In 2017 Wildlife Services removed 1,314 mute swans including 849 from 17 locations where trumpeter swans were also present. Some sites previously dominated by mute swans are now occupied by breeding pairs of trumpeter swans — a noteworthy success story in the native swans’ recovery program.

MDNR and Wildlife Services biologists continue to work together to educate the public about the problems caused by mute swans. Educational programs and future control activities prioritize sites based on the number of swans present, the presence of threatened and endangered species, such as trumpeter swans and wild rice (Zizania aquatic), and conflicts with humans. Special emphasis is placed on sites that have a conflict with threatened, endangered or native wildlife or vegetation.

Each year our teams continually monitor more than 150 mute swan control sites throughout the state. Fewer mute swans have been observed at sites where management efforts have been taken. The 2017 MDNR population estimate of 8,133 mute swans represents a 54 percent reduction from the peak observed in 2013. These trends demonstrate that integrated mute swan management has been effective and progress is being made toward Michigan’s long-term goal of less than 2,000 mute swans by the year 2030.

Management still needed

This winter aerial survey over Lake St. Clair during February 2013 showed a 50:50 mix of migrating tundra swans and resident mute swans. ©Dusty Arsnoe, USDA Wildlife Services

But it’s not time to declare victory. Continued mute swan management in the Great Lakes region is needed to ensure success of the native trumpeter swan recovery, decrease competition with other native waterfowl, reduce wetland habitat degradation and reduce the number of conflicts with humans. Every year since 2012 the number of mute swans removed has decreased, a trend that was anticipated in response to the overall population decline across Michigan. Clearly, the management program must continue to monitor and prevent reestablishment of the bird within high-priority sites — including state-managed natural areas and Great Lakes waters — while also continuing to reduce the statewide population towards the long-term goal.

As fewer mute swans are found within managed sites — mainly state-owned waters — private inland lakes will continue to harbor populations that provide a constant annual population source. In Michigan, mute swan management at privately owned sites requires landowner permission. In order to increase these management opportunities, Wildlife Services biologists will continue to explore outreach opportunities to educate the public about the problems the birds cause. Encouraging inland sites to enroll in the nest destruction program offers a reasonable and safe solution.

To help inform future management decisions, Michigan State University, MDNR and Wildlife Services are collaborating on a five-year mute swan research project. The project is aimed at improved tracking of seasonal mute swan movements, better estimations of birth and death rates, and an enhanced understanding of the swans’ population growth potential in the Great Lakes region. This movement data and population information will be used to better inform management strategies, including the identification of new locations with large concentrations of the birds, particularly during winter ice-over conditions.

Reaching a point where these beautiful swans are no longer beasts is no doubt a worthy management goal for the ecological health of the Great Lakes region.

Protecting a ‘Natural Treasure’ — The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative

The Great Lakes comprise the largest system of fresh surface water in the world. They contain 21 percent of the global surface freshwater and provide valuable habitat for fish and wildlife from New York to Minnesota. In a 2004 executive order calling the Great Lakes a “national treasure,” President George W. Bush tasked the Environmental Protection Agency with developing a regional collaborative approach to protect and restore the Great Lakes in accordance with a 1972 pact between Canada and the United States to improve Great Lakes water quality.

EPA made restoration of the Great Lakes ecosystem a national priority. By 2010, the agency launched the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) to strategically target the most significant ecosystem problems. A task force of 16 federal agencies and many state governors identified critical focus areas, one of which was preventing the introduction and establishment of invasive species. Since then, more than $1.7 billion has been spent on efforts to protect and revitalize the treasured national ecosystem.

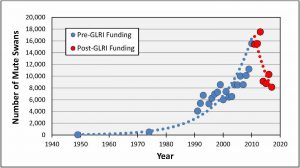

Beginning in 2011, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative provided additional funding to prevent further expansion of mute swans in the Great Lakes region. The funds have supported Wildlife Services’ integrated mute swan damage management plan in cooperation with the Michigan Audubon Society, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, MDNR’s wildlife and parks and recreation divisions, several county and local governments and private lake associations.

SIDEBAR

Michigan mute swan population estimates before and after GLRI funding support. Recent surveys (2014-2017) demonstrate a sustained reduction in the mute swan population size post GLRI funding. ©MDNR

Collaborative Mute Swan Projects

Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, Ohio and Wisconsin have managed mute swans on all five Great Lakes in state-identified priority areas, including state-managed natural areas and public and private waters.

Indiana

In 2012, Wildlife Services-Indiana began coordinated work with the Indiana Department of Fish and Wildlife in a GLRI project aimed at controlling the spread of mute swans there. The work concentrates on northern Indiana lakes, with a focus on removing adult pairs to prevent recruitment. The IDFW permits take on state and federal wildlife lands, due to the properties’ importance to native wildlife. The majority of removals are conducted during the nesting period when birds are territorial and during the molt when birds are less likely to abandon a site. Nighttime removal, especially on high-activity waters, may be incorporated to ensure safer operations for agency personnel and the public. Wildlife Services also developed protocols, distributed by IDFW with permits, for lake associations to follow for nonlethal management, nest destruction and lethal removal.

Wisconsin

In Wisconsin, GLRI funds from 2011-2016 enabled Wildlife Services-Wisconsin to manage mute swans utilizing lethal removal of adult birds and nest destruction. In 2011, Wildlife Services began management efforts in Door County in 2011 where a group of 97 mute swans was located. By 2016, surveys showed no mute swans in Door County, and state-endangered trumpeter swans were sighted in areas where they were not previously observed. In more than a dozen operations, a total of 28 mute swans were removed. In lakes where management is not possible, agency biologists observed three breeding pairs nesting successfully.

An adult female mute swan wears a GPS collar used to assist in estimating survival rates and tracking movements. The data collected will better inform future management decisions. ©Randy Knapik, Michigan State University/MDNR

New York

New York mute swan populations peaked at 2,800 in 2002. Well-established populations remain in Long Island and the lower Hudson Valley, with a smaller rapidly increasing group in the Lake Ontario area. Managed under New York State Environmental Conservation Law, mute swans may not be handled or harmed without authorization, and release of captive mute swans into the wild has been prohibited since 1993. The state agency, joined by Wildlife Services with GLRI funding, has removed adult birds and addled eggs in the Great Lakes area. A statewide plan for mute swan management, released in January 2014, received extensive and divergent comments leading to additional research and planning. Subsequently, Wildlife Services limited work with mute swans to nest destruction. Mute swan populations have recovered in the Great Lakes upstate area. A third draft of the New York plan, which adopts a regional approach to downstate and upstate populations, was released for comment in September 2017.

Ohio

In Ohio, mute swan management is integral to the threatened trumpeter swan recovery plan, under a strategy endorsed by a public-private coalition of conservation agencies and organizations. The state developed the plan after a regional mute swan summit in an effort to curb damage associated with mute swan populations. GLRI funding allowed for more concentrated operations. From 2013 to 2017, Wildlife Services-Ohio was able to augment state management actions by conducting lethal take of adult swans on public and private properties. Trumpeter swans have been observed in previous mute swan territories, and a 2016 survey showed a 20.4 percent increase in pairs and a 30 percent increase in cygnets over the last five years.

Illinois

Wildlife Services-Illinois conducted an aerial survey in cooperation with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources to document the presence and overall abundance of mute swans throughout the state. This new survey of distribution and population will be used by the state to revise its management plan.

Wildlife Services-Illinois conducted an aerial survey in cooperation with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources to document the presence and overall abundance of mute swans throughout the state. This new survey of distribution and population will be used by the state to revise its management plan.

Dustin (Dusty) Arsnoe, MS, is a wildlife biologist for USDA’s Wildlife Services program in Michigan.

Dustin (Dusty) Arsnoe, MS, is a wildlife biologist for USDA’s Wildlife Services program in Michigan.

Anthony (Tony) Duffiney, BS, is director of USDA’s Wildlife Services program in Michigan.

Anthony (Tony) Duffiney, BS, is director of USDA’s Wildlife Services program in Michigan.

Header Image: A male mute swan aggressively defends his Antrim County, Mich., breeding territory by attacking a native trumpeter swan in flight. The invasive swans negatively impact habitats for the state-listed trumpeters. ©Jenilee Whistler