Share this article

Giant stag beetles: Ecology, genetics and distribution

Up to 30 percent of all forest insect species depend on wood that is dead or dying. “Such species are among the most threatened insects in Europe,” says U.S. Forest Service scientist Michael Ulyshen. “However, very little is known about their diversity or conservation status in North America.”

Giant stag beetle larvae eat dead wood. They have a vital role in decomposing fallen trees. ©Michael Ulyshen, USFS

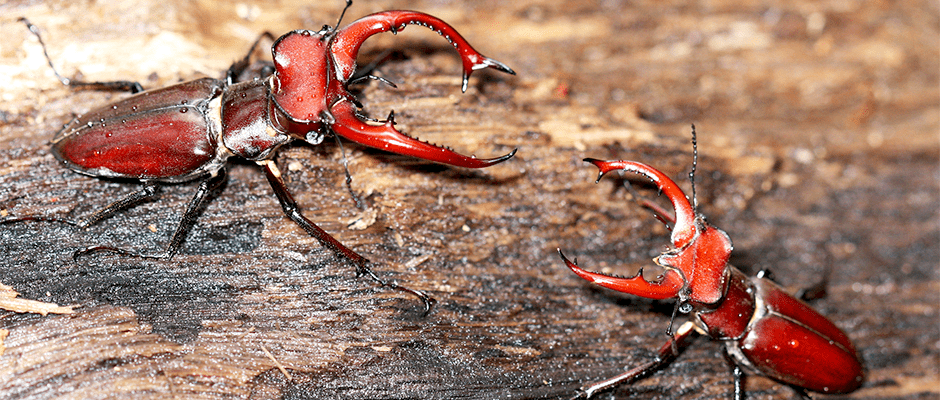

In the U.S., the giant stag beetle is the largest insect associated with dead wood. Including their large mandibles, giant stag beetles can reach nearly two and a half inches long. Despite their impressive appearance and popularity among insect collectors, their ecology and habitat requirements are relatively unknown. “We do know that giant stag beetles are highly dependent on dead wood,” says Ulyshen. “In many managed forests, there’s not much dead wood available.”

Ulyshen, an SRS research entomologist, recently led a study on giant stag beetles, which are also known as Lucanus elaphus. The study was published in the journal Insect Conservation and Diversity and provides information on the giant beetles’ ecology, genetics, and distribution.

Starting in 2014, Ulyshen and his colleagues surveyed Mississippi forests for a year, searching for beetle larvae underneath logs and in rotting stumps. The scientists found 75 stag beetle larvae, most of them in extremely decomposed wood. Larvae were found in wood of many different sizes and states of decay.

“Some logs were from oak, beech, or Chinese tallow trees but most were too decomposed to identify,” says Ulyshen. “Our findings underscore the value of highly decomposed hardwood logs to the species”.

There are 24 stag beetle species in North America, and to the eye, giant stag beetle larvae are indistinguishable from related species. Ulyshen and his colleagues reared larvae to adulthood to determine their identity. The scientists then sequenced their DNA to facilitate future identification through molecular methods.

“We didn’t find any larvae from the other stag beetle species,” says Ulyshen. “Their absence suggests that they have different habitat requirements.”

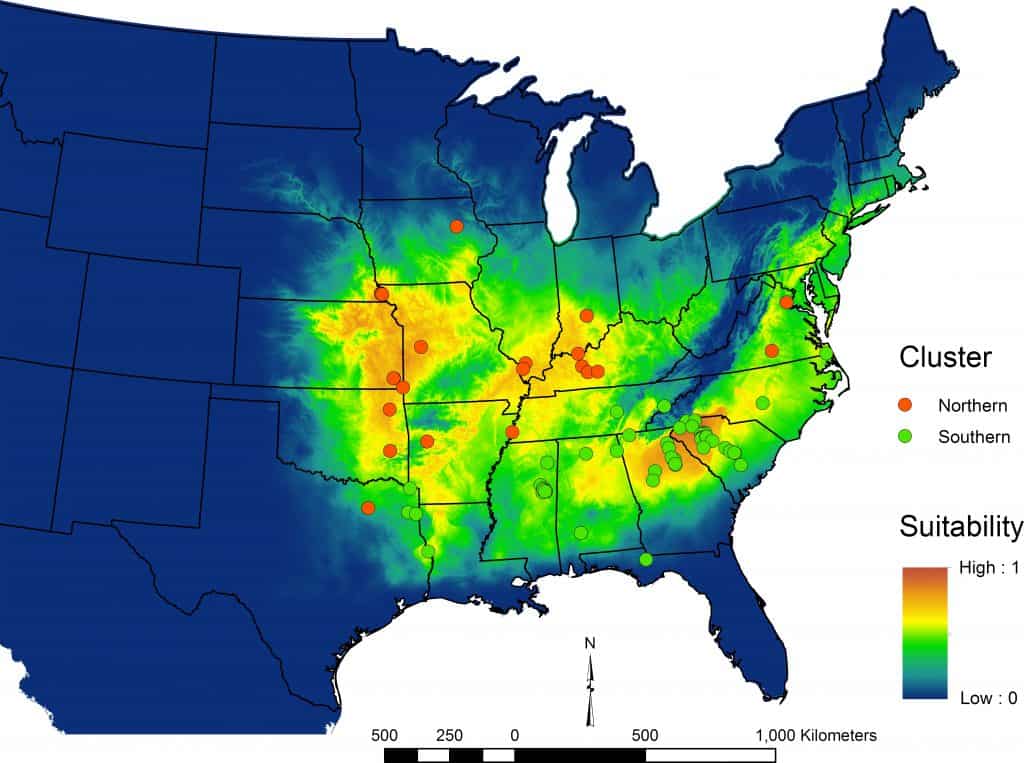

All of the larvae were found in wood that was wet or damp. Some of the logs had probably been carried by floods, and others would have been covered by flood waters at times. “Our study suggests that giant stag beetles primarily use lowland forests for breeding,” says Ulyshen. “Ecological niche models largely support this conclusion and indicate that mountainous areas may provide less suitable habitat.”

In addition to searching for larvae, the scientists hung traps in tree branches in Georgia hardwood forests. They captured six adult males in the traps. “We found equal numbers of male and female larvae, but only captured males in the traps,” says Ulyshen. “Males are probably more likely to fly around.” Similar behavior has been documented in other stag beetle species.

A closely related stag beetle, Lucanus cervus, was once common in Europe, but has declined substantially and is now considered threatened.

“There are some parallels in the threats facing both stag beetle species,” says Ulyshen. “While our study provides some valuable information about the ecology and habitat requirements of the giant stag beetle, more research will be needed to assess the species’ conservation status throughout their range.”

Read the full text of the article.

For more information, email Michael Ulyshen at mulyshen@fs.fed.us.

This article originally appeared on CompassLive, the online science magazine of the U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station (SRS). View the original article here.

Header Image: Male giant stag beetles fight each other with their enormous mandibles. ©Michael Ulyshen, USFS