Share this article

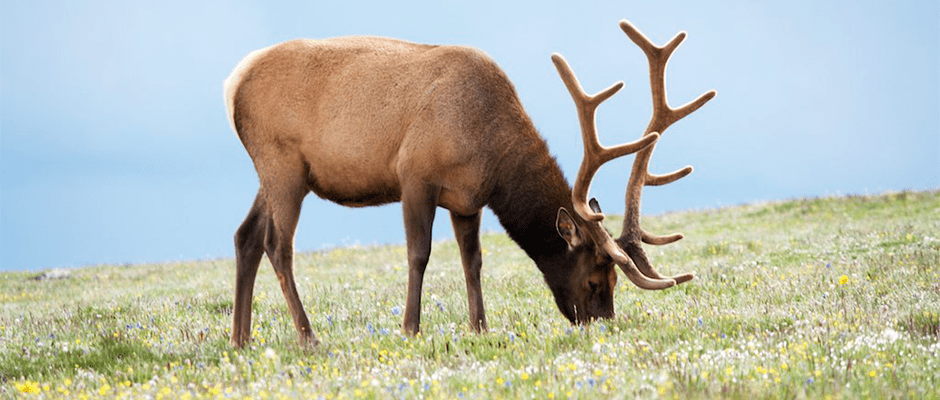

Bees compete for flowers with elk, deer and cattle

Native bees play a key role in ecosystems by pollinating plants, but on many landscapes in the West, they may face competition from elk (Cervus elaphus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and cattle (Bos taurus) that eat some of the same flowering plants on which bees forage for nectar and pollen. A team of researchers is trying to determine what impact grazing might have on native bees.

The decline of honey bees has made a lot of headlines in recent years, said Sandy DeBano, associate professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Oregon State University, but native bees provide the same sort of pollination services for ecosystems that honeybees provide for agriculture, and many of those species are struggling.

“Some of our native pollinators are declining or becoming extinct,” DeBano said, so it made sense to look at what competition bees may have for the flowers they rely on for nectar and pollen to feed their larvae.

Her research team reviewed literature about diets of bees and deer, elk, and cattle, and published its findings in a paper in Natural Areas Journal. DeBano was the lead author on the study. “Understanding the relative role of common big game species like deer and elk in impacting flowers relied on by bees is pretty important,” said co-author Mary Rowland, a TWS member and research wildlife biologist with the Pacific Northwest Research Station of the U.S. Forest Service. “We tend to look at competition between deer and elk for forage, or between livestock and big game, but I think we need to look at broader ecosystem issues.”

The study combined field data about which bees were present, when they were present and what flowers they were using with a literature review of the flowers that were reported in diets of deer, elk and cattle. Researchers found high potential overlap in several species of flowers including common yarrow (Achillea millefolium), western mountain aster (Symphyotrichum spathulatum) and several species of clover (Trifolium spp.) and penstemon (Pentstemon spp.). Their results suggest that for the flowering plants in their study area, elk have the most potential dietary overlap with bees.

“There’s very little research on how grazing affects floral resources for bees,” Rowland said.

The research was conducted on the Starkey Experimental Forest and Range in northeastern Oregon. Researchers took advantage of grazing exclosures in place as part of an ongoing riparian restoration project, which included the planting of over 50,000 native trees and shrubs. They used exclosures to create four types of grazing treatments: one tall enough to keep out all the grazers, one that allowed grazing by all ungulates, one that excluded cattle but allowed deer and elk in, and one with a gate that allowed cattle to graze but kept deer and elk out.

Researchers have identified more than 180 species of native bees at the site, including the imperiled western bumble bee (Bombus occidentalis), which has been petitioned for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Researchers hope future studies will help pin down when the ungulates are consuming the flower species to have a better idea of which bees might be affected.

“There’s a lot of press and understanding that pollinators provide key ecosystem services,” Rowland said, “but they’re still undervalued and under-studied, especially wild bees.”

Header Image: A recent study found grazers such as elk, deer and cattle eat some of the same flowering plants that wild bees rely on. ©Rob DeGraff