Share this article

Award recipient turns students on to science

Nominations for the 2017 Excellence in Wildlife Education and Conservation Education awards will be accepted through May 1. Visit the Conservation Education Award and Wildlife Education Award webpages by clicking the links above, or visit https://wildlife.org/engage/awards/ to learn more about all TWS awards.

Wyoming is home to plenty of charismatic species like grizzly bears and wolves, but it’s chipmunks that University of Wyoming professor Merav Ben-David is known for helping her students study.

A mainstay of her Wildlife Ecology and Management class, the chipmunk project gives undergraduate students hands-on experience in wildlife biology, and it’s just one example of Ben-David’s commitment to education that earned her the 2016 Excellence in Wildlife Education Award.

“Her name immediately popped into my head for the award,” said Elizabeth Flaherty, associate professor of wildlife ecology and habitat management at Purdue University and a former teacher’s assistant for Ben-David. Flaherty nominated Ben-David for the award, which honors exemplary faculty members who excel in teaching, advising, research activities, academic program development or educational leadership.

Another award that recognizes wildlife educators is the Conservation Education Award. This award covers a diversity of activities, including particular works of great merit and programs that represent sustained effort that can achieve great significance over the years. The award is given on a rotating basis in the categories of writing, audio-visual works, media and programs. This year’s category is media.

“It’s not just her classroom teaching,” Flaherty said. “She’s an amazing undergraduate advisor for the TWS student chapter at the University of Wyoming and she has created all these amazing opportunities for students.”

A professor of zoology and physiology, Ben-David has a reputation for taking time to visit with her graduate students at far-flung field sites, Flaherty said, even if it means traveling to Alaska to observe northern flying squirrels or sailing on an Arctic icebreaker in search of polar bears.

Each spring break, she leads the school’s TWS chapter to the Western Region Student Conclave. She turns the road trip into a Western Ecosystems course, exploring various habitats and speaking with wildlife specialists along the way.

Yet it’s the study of least chipmunks (Tamias minimus) that many students remember her for, Flaherty said, because it is often their first experience —and sometimes their only experience — working in wildlife biology. Students take part in live trapping, vegetation surveys, data analysis and other activities that are part of a wildlife biologist’s routine.

“The students develop a real sense of ownership with that project,” Flaherty said. “She uses it as a way to teach students all the different methods that are involved in research and monitoring and population estimation. She brings up the chipmunk study through pretty much every lecture she does, so the students have this really dynamic experience.”

For Ben-David, who was recently named editor-in-chief of TWS’ Wildlife Monographs, it’s a way to turn students on to the field, regardless of their background.

“They develop a personal attachment to science, wildlife biology and nature,” she wrote in a teaching statement.

It’s also a way to reach out to students who might not otherwise pursue wildlife biology. Usually, research opportunities only go to the top students who have demonstrated an interest in wildlife biology, she wrote. “The system I developed at UW allows all students to experience science first hand, to engage and connect, to develop their own questions and try to answer them.”

That’s important, she wrote, if educators are serious about increasing diversity in science, technology, engineering and math — or STEM — careers.

Flaherty said working with Ben-David inspired her to pursue a career in education, so that she could turn on her own students to wildlife biology.

“Experiences with Merav really impact students’ lives and their careers,” Flaherty said. “So many of them go on to do amazing things.”

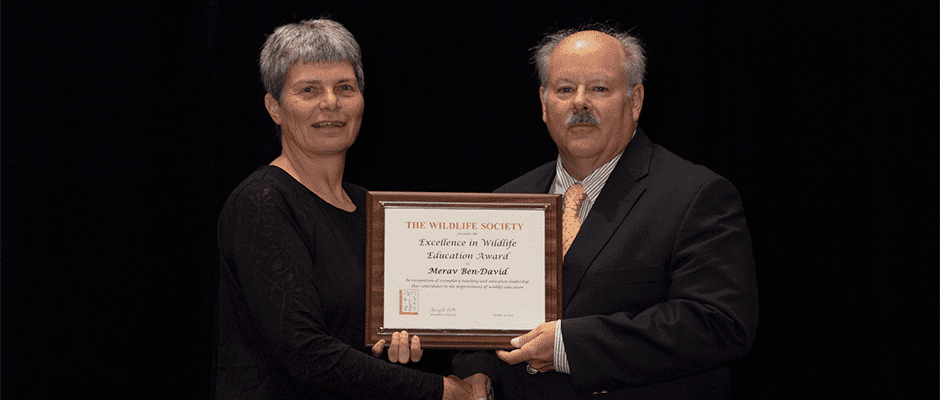

Header Image: University of Wyoming professor Merav Ben-David accepts the Excellence in Wildlife Education award from former TWS President Gary Potts at the 2016 Annual Conference in Raleigh, North Carolina.