Share this article

JWM study: Mountain lions dominate elk calf mortality

Mountain lions and black bears and wolves — oh my! Researchers recently wanted to determine the role of these three carnivores in the recent decline in elk calf survival or recruitment in the southern Bitterroot Valley in west-central Montana. The decline appears to have occurred in the last decade, according to the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Park’s annual recruitment surveys that date back to 1965, with elk calf recruitment reaching historic lows in the Valley in 2009.

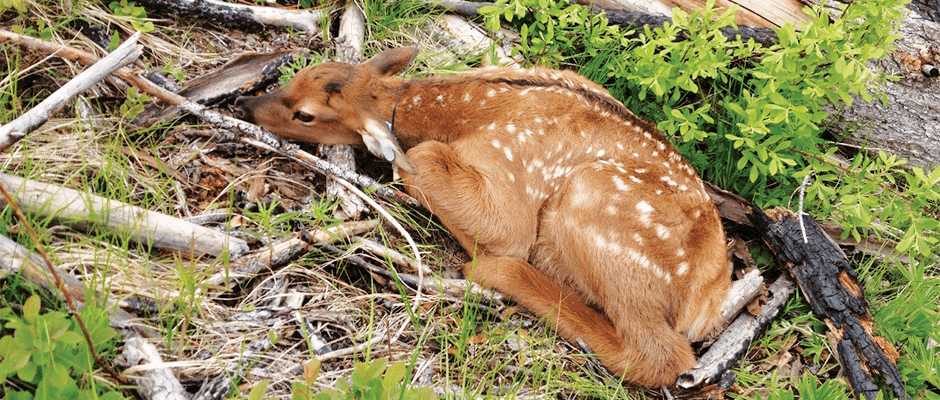

As part of their research published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, the scientists divided their study into the East and West Fork areas of southern Bitterroot Valley and examined elf calf recruitment there from the summer of 2011 through the spring 2014. They captured newborn elk calves that were less than a month old as well as 6-month-olds and attached a light-weight radio ear tag that emitted a signal when the tag stayed motionless for four hours suggesting mortality. Eacker remembers spotting the first calf he tagged from far away and then finding tiny hoof tracks in the dirt that led him and a colleague to a motionless calf. After detecting the signal, the researchers quickly arrived at the scene to determine the fate of the calf.

The researchers used helicopters to dart and then tag 6-month-old elk calves during the winter. ©Craig Jourdonnais

“We were basically doing CSI or crime investigation in some ways,” Eacker said. After locating the radio ear tag using telemetry, the researchers looked for evidence of predation around the mortality site such as signs of a struggle. Then, they conducted a necropsy where they looked for puncture wounds on the carcass, subcutaneous hemorrhaging and other trauma that might have occurred while the animal was dying. Eacker says that determining the cause of mortality with high certainty can be challenging in some cases, especially when elk calves are consumed quickly as newborns.

Overall, the researchers captured 286 calves over three years: 226 as neonates in the summer and 60 as 6-month-olds in the winter.

After analyzing their data, Eacker and his team found that mountain lions appeared to be the main predators of elk calves year-round, except in the first week of the calf’s life when black bears proved to be a greater threat. “Mountain lions hadn’t gotten much attention compared to wolves, and the hunting public tends to fixate upon wolves as if they’re driving everything in the ecosystem from a predation standpoint,” Eacker said. “It just wasn’t the case with elk calves in our study.”

Although wolves had recolonized the Bitterroot Valley in the early 2000s, hunting and trapping as well as management efforts helped reduce the number of wolves in the area. However, researchers found during the study that mountain lion density was among the highest reported in western North America. This may have been expected since there was a major reduction to the mountain lion harvest quota in the decade leading up to the recent decline in elk calf recruitment.

Eacker says it’s important to understand that managers and the hunting public should not assume that one predator such as wolves are driving predation in a system, especially where wolves and grizzly bears are rare or recovering.

“I think it’s relevant, especially because we’re seeing wolves recolonize in other western states,” Eacker said. “The main take-home is that even though some folks tend to do so, we can’t assume that wolves will be driving the predation in the system.”

Header Image: An elk calf fitted with a radio ear tag. These tags were used to alert researchers when a calf had died. ©Daniel Eacker